Slavery: the Haunting Legacy of Sterilization Abuse in California State Prisons

By Tala Khanmalek

Last year the Center for Investigative Reporting (CIR) announced that nearly 150 female prisoners in California were sterilized without consent from 2006 to 2010. The state had been paying doctors to perform tubal ligations without required approval. In fact, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) contracted medical services for the surgical procedure in violation of both state and federal laws on the basis that it would cut welfare costs. Around the same time of the announcement, I read about J. Marion Sims (1813-1884), better known as the “Father of Gynecology,” and more specifically, modern surgical gynecology—in the annals of Western medicine. However, though perhaps the most famous surgeon in the 19th century American South, Sims was also a slave owner who conducted nonconsensual medical experiments on enslaved Black women. And though centuries apart, these two narratives of non/consent, are historically and conceptually related. When considered together, they expose a haunting legacy of systematic regulation of Black women’s reproductive health since the era of legal slavery. Simultaneously, they expose the history and politics behind present day sterilization abuse in prisons.

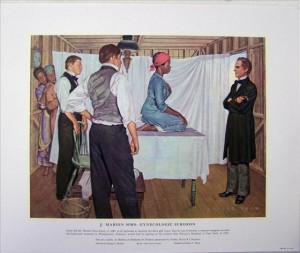

Harriet A. Washington’s Medical Apartheid (2006) begins with a painting of Sims observing Betsey, an enslaved woman, along with two other white male physicians in preparation for an experimental surgery. “Was Sims a savior or a sadist?” asks Washington. “It depends, I suppose, on the color of the women you ask. Marion Sims epitomizes the two faces—one benign, one malevolent—of American medical research.” The history of American medical research, she goes on to show, reflects racist ideologies from enslavement to contemporary forms of subjugation. In the antebellum south, slave owners contracted physicians like Sims to increase the birthrate of enslaved Black women using pseudoscientific methods that perpetuated sexual violence. Because slave status was inheritable by law, masters claimed ownership of unborn children, thereby guaranteeing a future slave labor force, despite abolition of the international slave trade (1808). Ownership rights thus extended to the bodies of enslaved Black women for unrestrained experimental as well as sexual exploitation. With no legal protection whatsoever, enslaved Black women were vulnerable to what Washington calls “experimental suffering” at the hands of physicians who were more often than not, their slave masters as well. As she chronicles, the systematic reproductive regulation of Black women continued in the postbellum decades, albeit to decrease the birthrate of those deemed eugenically inferior.

What are we rendering unintelligible about present day sterilization abuse and medical discrimination at large when we stop short of racial slavery and settler colonialism? In her Huff Post article (co-authored with Tony Platt), Alexandra Stern situates the CDCR violation within California’s history of eugenics, whose sterilization law later served as a model for the Nazi regime. Stern points to “a discernible racial bias” in the state’s sterilization programs, yet focuses her analysis on eugenic racism. Situating the unauthorized sterilization of female prisoners within eugenics alone erases interconnected pre and post-war campaigns of state-sanctioned reproductive regulation targeting women of color while reserving the individual right to birth control for white women.[i] Most importantly, it erases the historical and conceptual antecedents of eugenics itself, which was another face of the color and continent based racism that legitimized colonization and enslavement. Sterilization abuse in California state prisons is just as much a part of the state’s eugenic past as selective procreation during the era of legal slavery. In the words of Loretta J. Ross, co-founder of the SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective: “This is an ugly history repeating itself.” The CDCR violation evidences an unbroken chain of targeted reproductive regulation carried on, in part, by today’s prison industrial complex. That is, a 21st century attempt to control bonded women’s fertility, which literally bespeaks the masters tools.

According to the American Civil Liberties Union, “there are now more than 200,000 women behind bars and more than one million on probation and parole.” Lack of legal protection for cis and transgender female prisoners caught in the criminal justice system is of ongoing concern. The shackling of pregnant women during childbirth remains among the many issues regarding adequate medical care that characterize the inhumane conditions of confinement. In her article about the CDCR violation, “Eugenicists Never Retreat,” Ross reveals that, “At least a couple dozen more prisoners—predominantly Black, Latina, and indigent women and transgender people—reported being sterilized by hysterectomy and oophorectomy under highly questionable and abusive circumstances.” As she emphasizes, violating the human right of female prisoners to have children is fundamentally, an “immoral act of genocide.”

While institutionalized bioethics fails to account for incarcerated women, prison abolition has always been a central component of the reproductive justice movement. A group of African American women, including Ross, coined the term “reproductive justice” in 1994 following the International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo, Egypt. However, Ross maintains that informed consent “cannot realistically occur in the neglectful, coercive, controlling context of prison health care.” The underlying logic of dehumanization scaffolding the prison industrial complex borrows directly from the southern slavocracy. Similarities between the CDCR violation and Sims’ experimental surgeries are more than a semblance of the past; they constitute the enduring racialized and gendered dimensions of biopolitical subjection.

[i] See Harriet A. Washington’s Medical Apartheid (2006), Dorothy Robert’s Killing the Black Body (1997), and Angela Y. Davis’ Women, Race, and Class (1981).

__________________________________________________

Tala Khanmalek is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Ethnic Studies Department at UC Berkeley. She is currently a Visiting Scholar at UC Santa Cruz’s Science and Justice Research Center. As the former Executive Editor of nineteen sixty nine, she edited the volume on Healing Justice.

Tala Khanmalek is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Ethnic Studies Department at UC Berkeley. She is currently a Visiting Scholar at UC Santa Cruz’s Science and Justice Research Center. As the former Executive Editor of nineteen sixty nine, she edited the volume on Healing Justice.

Pingback: Sunday feminist roundup (16th November 2014) (feimineach/com)