The Good Death of Toni Cade Bambara

By Guest Contributor on November 18, 2014By Clyde Taylor

I was surprised to find myself standing at the memorial for Toni Cade Bambara at Painted Bride in Philadelphia. Some thoughts had come to me of things wanting to be said that I could add to the oral narrative of remembrance being woven that afternoon. Some of the things I said I try to recall here, plus another few hind sights.

There was like a remembered scene where Quincy Troupe, Ishmael Reed, Eugene Redmond, and myself would be riffing off a conversational theme whose tune would be something like, “Ooo wha badda dee wang wabba zap zap.” And Toni would walkup and, without missing a beat, throw in “yah wee zou nifferooo banna siou ow.” A quartet become a scrappier quintet. Toni had this flair despite all her aura and labor as a feminist forerunner, a special way of talking with men that held little of that special regard that settles in sooner or later in talk between women and men, a scramble between contestation and courtesy—it just wasn’t there when you talked to Toni. This was part of her genius in being with people. She met you just where you were and with second sense met you where you had been three years ago and maybe where you would be two years later. The vision thing, where she seemed to be able to see around corners. A casual conversation with her, and you could get a clearer sense of where you were and, relieved, where you wanted to go.

Toni’s cool with men, who almost universally loved her, fed a weakness I have for women who evince gallantry. Her fearlessness was infectious, the swagger in her voice carried a charmed cockiness. Her confidence could, to quote something she said in Midnight Ramble, “put a bit of bone in the back.” I told her one time I was having doubts about doing film criticism, because I didn’t remember details of films the way I wanted. She said, “Aw Negro, just go ahead and do it.” So I did.

She met historical and personal realities without alienation or mask, without a face to meet the faces that you meet. Reinforced by the tonality of the embattled sixties, this broke down to a charming face in your face. There’s a line from June Jordan that captures this voice, its time and place, probably aimed at one of the young people that Toni and June were transforming in their classes. “Come over here. Where you from?” At one small gathering, Morrison and Bambara were both present, at ease in their classical, gnostic friendship when, to avoid confusion of which Toni was being talked to, I suggested calling Bambara Toni the Enforcer (holding a bit of breath: no better way to make an enemy that to play around with their name or appearance). Toni rolled her eyes over the ceiling—I think she often did this to visualize her own private thesaurus of possible word choices—she loved words and wanted them to be precise—and then said, “I like that.” (Another gesture she had was to dance her fingers in the air about eye level as she spoke, as though elegantly playing a piano tune to go with the flow of her words.) Toni the Enforcer made sense, more as Toni the Empowerer, about as active as a community and cultural organizer as a writer. Black filmmakers, young Black feminists, developing writers and political organizers found their way to Toni and came away mobilized.

The time I called Toni the Enforcer was during a film symposium that Morrison had organized at the State University of New York at Albany. We were gathered in a conversation pit at Morrison’s apartment during a break in the official program—Hortense Spillers, Haile Gerima, Martin Wilson, the two Tonis, and myself. I put a question to these decorated veterans of Black cultural wars. Was the role we were playing in the national academic scene one of giving comforting face to regimes insincerely dedicated to our communities, in effect serving two masters, being used by a system that needed us as buffers against the interests of our bio-social roots, whose values were at the top of our priorities? I asked this question then because these front-forward thinkers were the best to ease my troubled mind. The talk pushed the question around like a soccer ball. Morrison made a powerful statement. Before that, Bambara brought the whole thing into a manageable, intelligible space. Her words brought to my mind a saying that circulated among militant activists in the 1960s: Some people you entertain; some you teach; and some you lead. But that is not what she said. Her remarks were on the line of “we have to be about changing the institutions that impact on us while transforming ourselves into a more intelligible, irresistible presentation of our reality.” This is a pitiful paraphrase of her elegant speaking. I use it to call to mind one of those times when Toni could shape a harmonizing dialectic, bringing everyone to a higher realization of possibilities. Ousmane Sembene, the great Senegalese film director, said, “In Africa a man if culture is one who has the right word for each occasion.” Bambara operated like an African “man” of culture. Transformation was one of the key words in her word-bank.

There was a fertility in Toni’s mind as she opened it in conversation that was almost uncanny. It was like four intelligent beings were feeding her some choice ideas which the controlling center would digest and come out with the richest resolution. Some of these internal monitors had such a restless acquaintance with past experience that they almost prefigured future possibilities. She gave some brilliant keynote speeches in the late nineteen-eighties, which need to be sought out and preserved, and which were marked by revelatory facts and details. I asked her how she came to possess these arcane, astonishing historical facts. Whenever she visited a town to do a reading or talk, she told me, during breaks she would saunter down to the City Hall or other locations and go down into the basement and dig into archival documents, newspapers, censuses, obituaries, announcements, statistics, reports, and find incredibly remarkable tell-tales. In conversation, an event set around 1920s would provoke her to scan the ceiling and ruminate out loud: That was a year after the Chicago riot, just before the Tulsa massacre, the migration is going full steam…No doubt, all writers do this under breath, especially novelists. Toni, I believe, built and sensed lush, fully fleshed scenes on these scaffolds.

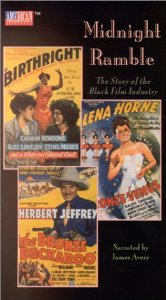

I was witness once to the magical working of Toni’s imagination and intelligence in this mode of her thinking. We were working on a doc about Oscar Micheaux called Midnight Ramble, co-directed by Pearl Bowser. We had good footage, fine oral narratives and talking heads who had known Micheaux and his scene. But we needed something more, a wider perspective on what it all meant, an integrating pulse. I suggested interviewing Toni on camera. Pearl liked the idea, and Toni agreed.

The night before she came to the set, we talked on the phone and she asked me what we wanted her to do. I said we’d like her to give a kind of thoughtful scrutiny, a social-cultural reflection or meditation using the skills of a novelist rather than a scholar and not necessarily as a film buff, which she was. Then, I made a slip of the tongue and spoke aloud what I hoped she might do; I said, “Something like Jimmy Baldwin might do.” I was way out of line, since nobody’s talking in the twentieth century ranks with Baldwin’s. To this day, I continue to hope that she understood it as a compliment. If anyone’s talk could be spoken of in the same sentence as Baldwin’s it was hers.

Toni’s gift to the film was silken and brilliant. To this day, film scholars follow her interpretation of scenes in Birth of a Nation without acknowledgement. She gives a very fetching, sooth-saying presentation. But here’s where the magic and uncanny intuition (imagination) comes in. At the point where we interviewed her, the film’s team was stymied. We were uncertain where to go next. We were debating what to include or leave out, where to find thematic drive, how to make the film hold together while moving the most useful information to the viewer. Without any prep information about these debates and uncertainties, Toni’s on-camera interview solved all our issues, resolved all of our creative differences, and in effect told us what our film was about and how to make its need a reality. Anyone looking at the film today will get a taste of Toni’s spontaneous canniness. But whatever they think of the film itself, they won’t peep how she clarified the team’s directions to give it whatever weight and point it can claim. Rightfully, hers are the last words on the voice track. At one screening in Atlanta, one viewer asked, referring to Toni, “Who was the film director who spoke at the end?” Literally, she wasn’t the director. But he had stumbled onto a half truth.

Her final illness stunned. It was like a beautiful script gone out of control with a perverse twist. It was difficult for her and her army of loyalists because the story made no sense, its ending too stupid for anything having to do with her creative path. Still, as Toni would, seeing as how she had a central role in this runaway narrative, she played her part with her usual finesse. The last time I saw her was in New York. Morrison had lent Toni her foothold apartment in Manhattan so she could say goodbye to her New York friends. Frail, she lounged on a sofa, hardy showing the fatigue of medications and several audiences lined up in a scheduled row.

She entertained Manthia Diawara, who went back with her to past Philadelphia years, and myself with her usual wit. But it was hard, making conversation without directly acknowledging the presence of It in the room. The It’s presence was as inexplicable to her as to any of us. When death comes along in its usual routine, it often leads survivors to thoughts of their own mortality. But I doubt anyone had such thoughts when Toni was leaving us. All we could think of was loss to ourselves and to the world. She was too rare for us to compare our life’s journeys to hers. Later internet years have produced more air kissing and “I love yous” at the end of phone calls—cutesy stuff that wasn’t exactly Toni’s groove. I am certain, though, that she always heard love in the laughter of friends talking with her.

So young she was to be leaving us. Among other things not finished was a particular mystery her life story had for me. When we talked her stories made turns that made me wonder could she be older than me, which was factually not possible, and she always looked young and lively enough to be a younger sister. She had lived so fully, had crammed so many lives and adventures into her time span. But there was another snag: the chronology. She seemed to have known intimately and as peers people much older than she. It was more than her being a prodigy. I think she had a way of knowing and experiencing that extended the range of time and space, that what people talk about as creative memory was virtuosic with her. Maybe, with her mental gifts, she experimented with her tools of connections and transformations. One example. When I told her I was going to Salvador da Bahia for a stretch, she said, “Say hello to the Sisters of the Good Death for me.”

When you’re talking to a brilliant mind like Bambara, you don’t interrupt with dumb questions like who, when and what—details that might bring her utterance down from a level impeding a poem being born in front of your eyes. At Painted Bride, I confessed that if she told me she kicked Booker T. Washington’s ass two years before he died, I’d believe her. Or at least I’d have to figure how to unpack that historical possibility.

I did go to Brazil, and as it happened, went to the town of Cachoeria in August when the Sisters of the Good Death hold their annual festival. They are awesome in their blossomy white dresses, head wraps and long beads, dancing with their admirers in some African Diasporic ceremonial dance, part samba part ring shout. Each Sister carries a gravitas in her well-soaked maturity, effusing spiritual power and conviction. I was obviously in the presence of some commanding humanity. One of the Sisters came up to me, put out her hand and said, “Give me money,” as if that was all the English she would ever have use for. Knowing how it would be spent, I gave her something that was more than small change.

The Sisters, I knew, carried on a tradition that began around 1820 as a communal support system to collect funds to buy the freedom of enslaved Africans. They also used their resources to celebrate the iyas, ancestral female spirits, and to give a resonant burial and sending off to those who lived during slavery and their descendants, who died free or fighting for liberation—in other words who lived a life worthy of a Good Death.

Watching the Sisters lead this hip-rumbling, drum-based ritual I wondered, “Say hello to the Sisters of the Good Death for me.” But how to say hello to them from Bambara, even if I had decent Portuguese? I wondered again at Painted Bride, as I talked about this puzzling moment. I was fumbling with the petty details that were beneath asking Toni when we had talked years before. Had she been to Brazil? Did she speak Portuguese? Had she met them? Did they know her? Then the thought of Toni’s spirit came to me. Yeah, they knew her.

Clyde Taylor has won many awards for literary and film criticism related to the African Diaspora. He founded the African Film Society in San Francisco in 1976, and wrote the script for Midnight Ramble: The Life and Times of Oscar Micheaux.

You may also like...

2 Comments

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

Pingback: Toni Cade Bambara: The Moment In-Between - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire

Pingback: Afterword: Toni Cade Bambara's Living Legacy - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire