It’s Not the Salt; it’s the Sugar that Will Kill You

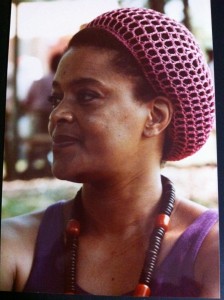

By Guest Contributor on November 20, 2014By Kalamu ya Salaam

Toni was unprocessed, natural sea salt. No chemical additives, too glitzy or trendy packaging, no capitalist mark-ups to sell shit for usurious profit. There was no Toni Cade book bag, special correspondence course, or exclusive MFA summer program with only 21 openings.

Forget all that. You know all these dudes on radio and the social media talking about “real talk.” Ten minutes with Toni Cade would leave them tongue-tied. Toni never wanted to talk about fantasy when reality was up in our face. It’s nice to conversate about rose-scented moments and reminisce about fond memories of good times past, but Jojo’s in jail, Esther was date raped the other night, Bib Mama’s diabetes is getting worse, and who knows where Uncle Alfred is.

Let’s talk about life. But don’t start with none of that woe-is-us crybaby bullshit. Toni would just glare at you. “Baby, what you gonna do about it?” Rather than a stern confrontational stance, she would put a steady hand on your forearm and lean slightly forward while lowering her voice to a conspiratorial level as if to say, I’m all in with you if you want take this on.

Or like she asked in her opus The Salt Eaters:

Do you really want to be well?

Toni Cade. Thank god, she was no saint. She was one of us, from the same earth, these same mean streets, this same-old, same-old community of captives and maroons, always striving to break free. Once we talked about making movies. One day, she told me in the husky half-drawl—that was Toni’s way of slowing down time to make sure you would catch on to what she was putting down—that she knew she had to go to where movies were if she wanted to learn about movies, so she booked a ticket…

(I could not then imagine Toni in Hollywood, but I would hear her out. You don’t interrupt a prophet when she is foretelling the way ahead.)

…and flew to Paris. Didn’t know anyone there. Didn’t have a stash saved up. Just knew she had to do what she had to do cause the only way to do it is to actually do it. And spent, if I remember correctly, at least a week in the Louvre examining French cinema.

You know I never asked her is she spoke French. That was not the point of the story, and was actually irrelevant, because with good movies, there is so much you can learn if you just pay attention. The three “Ls”: Look, listen, and learn.

She had emptied her bank account not to chase a dream but to make real a fervent desire. She was righteously stupid. The learned might call her impractical, impetuous, immature, and a bunch of other “im’s,” but Toni knew there was never any perfect time to break free. She was from the Charlie Parker school of righteous practice: Now Is The Time. Always now. Never later.

I remember asking myself, had I ever fully committed myself to anything that would be like Toni flying off to Europe. But wait, Toni, that’s not a black thing. Well, it is now; cause I’m black and that’s what I did.

Next.

I’m a man. Toni was a woman, eight years my senior. I never “hit” on her (back then most of us men, even those of us beginning to move in progressive directions, still had no popular progressive language to describe our interpersonal relations). I occasionally wondered what it would be like to be in a relationship with Toni, but I never approached her in that way. Besides my own moral code vis-à-vis women that I prided myself with holding to, what gave my musings pause was the realization that I was not as fierce as she. Toni was no one to take lightly, not even in your dreams.

I used to see her ‘round Mardi Gras time in New Orleans, sitting on a stoop waiting for the Indians, once (maybe it was twice) the other Toni was with her, Toni Morrison; the two Toni’s hung out in our city from time to time. And of course, we would cross paths all the time at conferences. I miss all those get-togethers we used to have, especially the Howard gatherings that John Oliver Killens initiated.

I always say that one of my most important essays from that period was commissioned by Toni Cade Bambara. I don’t remember what year it was, but that particular seventies D.C. conference was a rowdy affair (actually, all of our national cultural conclaves were rowdy, just different issues were the focus of our rowdiness). Anyway, I remember this was the year of black male writers whining about how black women writers were locking out the men from publishing, were receiving all the attention—some were even gender attacking the brothers, blah, blah, blah.

I had friends on both sides of the chasm.

Flying back home after the event, Toni and I shared the flight from D.C. to Atlanta, where she departed and I went on to New Orleans. Although I had spoken out on one of the panels, I felt like more needed to be said. These dudes were wrong and…Toni firmly raised the stakes as I played my hand. Sure the sisters should defend themselves, but what was also needed was for some men to be front liners in this anti-sexist struggle.

Kalamu, you ought to write it out.

That’s how my serious polemic, “If The Hat Don’t Fit How Come We Wearing It?: An Appreciation of Women Writing,” was born. That hours-long plane ride was when I graduated from being Toni’s friend and became her comrade. Later, we put together the mother tongue interview and overview, a piece of writing that has been anthologized in two or three of the Toni tribute books[1] that have come out over the years.

And this is my most treasured memory of Toni Cade Bambara. Make it real: She helped me to turn my feelings into life-long, visible, concrete anti-sexism work. Her work affirmed that not only was it ok, writing the working class reality of our people, confronting the failures and foibles, as well as uplifting the struggles and cultural innovations, was more than just ok. This work was necessary.

Not to receive applause or awards; indeed, we would often be ignored or vilified, dismissed as irrelevant or fanatical; even our closest friends and associates would provide shelter from time to time, but would seldom join us in the lonely fight against this now globalized capitalist-based system of oppression and exploitation. Naw, being on the front lines is a lonely fight.

Toni understood the solitary aspect of our search for a better life, and rather than try to make the struggle seem sweet, she told me, and told all of us, the truth. What was needed was not the sweetness of sugar suggesting that everything was going to be alright or that we had the chance now to join the descendants of our former slave masters at a White House banquet. America was offering us permission to wine and dine with them if we just acted right; and if we refused the invitation, well, America would make it hard on those of us who were smart enough to advance but dumb enough to retreat from equal opportunities.

Toni understood the solitary aspect of our search for a better life, and rather than try to make the struggle seem sweet, she told me, and told all of us, the truth. What was needed was not the sweetness of sugar suggesting that everything was going to be alright or that we had the chance now to join the descendants of our former slave masters at a White House banquet. America was offering us permission to wine and dine with them if we just acted right; and if we refused the invitation, well, America would make it hard on those of us who were smart enough to advance but dumb enough to retreat from equal opportunities.

This Toni was never going to win major awards, never going to be enshrined in the Academy. This Toni would look back on America and turn to salt before she would abandon her people.

I remember Toni. Every time I be discouraged, be tempted to throw in the towel, be offered some material gain to shut up or be silent, or stop refusing to pledge…every time disaster strikes, every time we do something stupid or something horrible (like the Atlanta child murders), I remember Toni, shake off the doubts and hesitations, take a lick of salt off the back of my hand to clear the bad taste out my mouth, and re-resolve to be true to my vows to never surrender, never give up, never quit. I remember Toni. And I travel on.

[1] Two of the books that feature Salaam’s conversation with Bambara are: Savoring the Salt: The Legacy of Toni Cade Bambara (Linda Janet Holmes and Cheryl A. Walls, Editors, Temple University Press, 2007) and Conversations with Toni Cade Bambara (Thabiti Lewis, Editor, University of Mississippi Press, 2012)

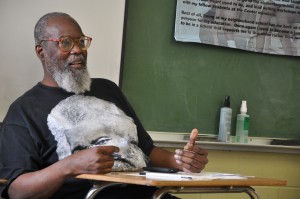

New Orleans writer, filmmaker and educator Kalamu ya Salaam is co-director of Students at the Center, a writing program in the New Orleans public schools. Kalamu blogs at neo•griot. You can also follow him on Twitter @neogriot or email him at kalamu@mac.com.

You may also like...

1 Comment

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

Pingback: Afterword: Toni Cade Bambara's Living Legacy - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire