How Many Black Histories We Still Don’t Know: An Interview With Simone Leigh

I am walking north on Buffalo Avenue from Crown Heights toward Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn, passing corner stores and apartment complexes, looking for the Weeksville Heritage Center. I don’t live in this neighborhood, and while I have friends and former partners who live in Bed-Stuy or Crown Heights, I have never put my feet on this particular patch of pavement. One block south of the center, I see a massive, derelict building, a shell of a building, empty, boarded up, covered in graffiti. This is St. Mary’s Hospital, closed in 2005 in spite of community outcry. The facility served a largely uninsured population, often in emergency rooms, and the fact that few patients could pay their bills created the economic crisis that led to its closure.

On the next block, the Weeksville Center itself is diminutive in comparison, a low and long building, modern, beautiful, all glass and wood and stone. Weeksville is the site of a nineteenth-century community of free black people who built homes, churches, and schools. Four of the original houses remain, facing the new building across a wide garden planted with wildflowers. The Weeksville Heritage Center, along with the arts organization Creative Time, and curated with Rashida Bumbray, invited four artists to engage with the communities in and around the center to create installations. I am walking north on Buffalo Avenue to see the art; Creative Time invited me to write about it.

On the next block, the Weeksville Center itself is diminutive in comparison, a low and long building, modern, beautiful, all glass and wood and stone. Weeksville is the site of a nineteenth-century community of free black people who built homes, churches, and schools. Four of the original houses remain, facing the new building across a wide garden planted with wildflowers. The Weeksville Heritage Center, along with the arts organization Creative Time, and curated with Rashida Bumbray, invited four artists to engage with the communities in and around the center to create installations. I am walking north on Buffalo Avenue to see the art; Creative Time invited me to write about it.

The installations are focused on Funk (Xenonbia Bailey), God (Bradford Young), Jazz (Otabenga Jones & Associates), and Medicine (Simone Leigh) as sites of black radical self determination, expression, and world building. The works were created in collaboration with community organizations (Boys & Girls High School, Bethel Tabernacle AME Church, Central Brooklyn Jazz Consortium, Stuyvesant Mansion), and are located at sites throughout the neighborhood. St. Mary’s looms in my mind; my mind is on medicine.

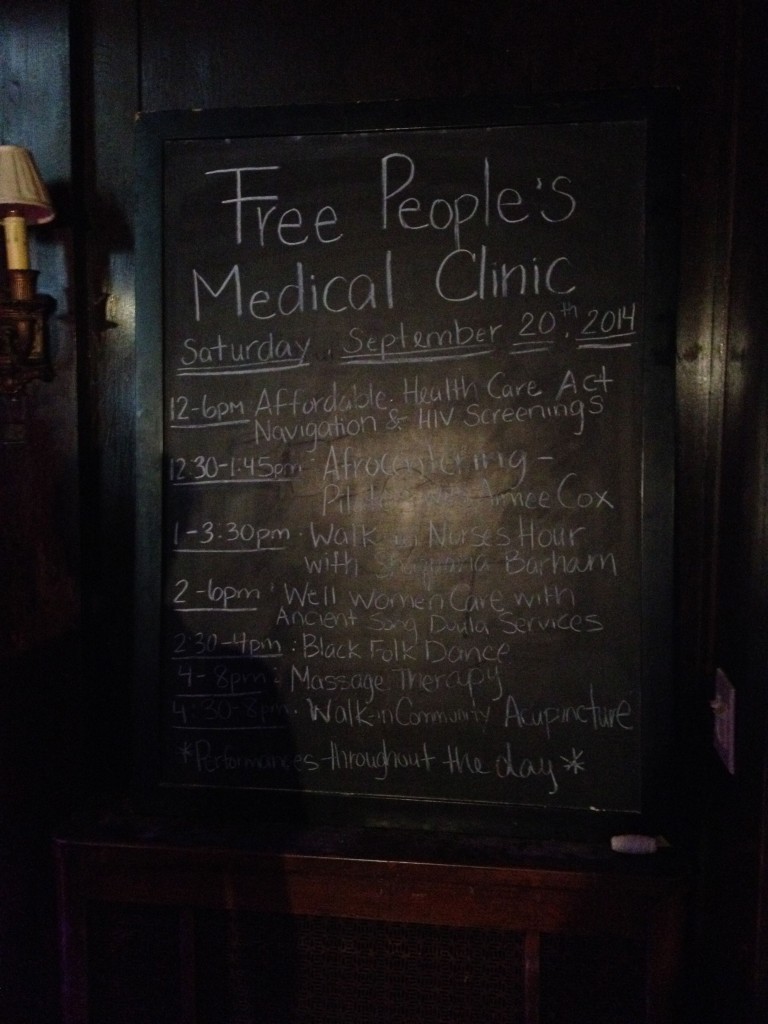

So I walk further north to visit Leigh’s installation at Stuyvesant Mansion. The building was the home of Dr. Josephine English, the first black obstetrician-gynecologist in the State of New York, and Leigh has made it into a Free People’s Medical Clinic, recalling earlier clinics set up by the Black Panther Party. It is bright outside, and warm, but inside the house it is cool and dark, deep blues and reds. A DJ booth sits just inside, and a slow beat pulses through the space. Black women dressed in nineteenth century nurses’ uniforms welcome me, ask if I would like to sign up for a free massage, a dance class, acupuncture.

I feel my whiteness so profoundly in this space. I know that black women have been caretakers of other people’s bodies historically. They still are. I feel as though my gaze, my very presence, my white male body that has so often been cared for by women, threatens the space. After I leave, I spend my week talking to friends about the ways that black women have given care; the ways white bodies have taken it. I talk about my own rural America, where health deserts exist too, and where models of self-care are nonexistent. I talk about black radicalism as a model for self-determination that can be used by all people, but also about how white people often appropriate ideas that come from oppression and rarely name the originator of the idea or work to ease to structures that created the suffering. I talk about how I can’t write about this work without writing about my own whiteness, and how I am tired of centering whiteness in the discussion of black art. I email my contact at Creative Time. I can’t write about this.

Simone Leigh (second from left) with Aimee Cox (third from left) and others in Stuyvesant Mansion. Photography by Shulamit Seidler-Feller, courtesy of Creative Time. 2014.

She asks me to reconsider. She offers to let me speak to Simone Leigh. I want to get out of Leigh’s way. And I want her to speak directly.

I go back and talk with Leigh, who has made an installation that is centered around the work done by black women – as nurses – to care for bodies, communities. On my walk from a friend’s house, I pass the Interfaith Medical Center, now the main site of emergency care in the neighborhood. Interfaith too has been in bankruptcy, and it has the longest Emergency Room wait times in the state of New York. I think about another friend who, just last week, sat in the Emergency Room at Harlem Hospital from 1 AM until 6AM without ever receiving care; she left and visited an Urgent Care clinic the next morning.

I arrive and meet Simone, and we sit in two chairs facing the same direction in the waiting room of the Stuyvesant Mansion listening to the heartbeat of the house from the DJ stand, and we talk about art, blackness, wellness, and care. I hold my iPhone up to record her words and mine, the contemporary world encroaching on the past. She offers me permission to speak, to write about her work. She extends to all of us an imperative to be the ones who carry her work forward – to care for ourselves and others – long after the Creative Time money runs out and the Stuyvesant Mansion goes back to being a community center and not explicitly a site of artistic intervention, just a house on a street in Bed-Stuy, among other houses, all filled with bodies and shaped by care.

* * *

I was wondering if you could speak about the collaboration with Creative Time and the theoretical framework behind the work.

Creative Time asked me to propose a project that would use what was already here in the community and I took that boundary really seriously: to use this community as the material of the project without bringing anything from the outside in. They told me they wanted it to speak to the historical impact of Weeksville in the community. In 2012, Malik Gaines and Alex Segade asked me to do a performance about the Black Panther Party, and specifically about Elaine Brown and her album “Seize the Time”. Trying to be a good artist, I wanted to read the most recent scholarship on the Black Panther Party and it was Alondra Nelson’s book Body and Soul, which is about the medical clinics. So it was already germinating when Creative Time came.

In general my work is concerning the representation of black women in visual culture. This was my first social practice project and the components of it are an extension of the work I was already doing in sculpture and installation and video. It’s not really that different for me, I think it’s different for other people because it’s live. But for me, these objects in the clinic are not that disparate, they are the same ideas at work. It is also a part of a long-term relationship I have with Rashida Bumbray; this is maybe the fourth of fifth exhibition we’ve worked on together, and I feel like we’ve been working together to develop a large project.

Was this project specifically trying to break down some of the barriers between art and health and self-care and to present some of the classes (yoga, dance) as performances themselves?

One of the reasons I have acupuncture or dance or yoga going on in the waiting rooms is because I wanted to have on display what was going on inside the rooms so the clinic is revealing itself in these performances. My original intention was to put a primary care clinic in the building, and I could not do that because our society is so litigious now that it is impossible. So one of the things I discovered along the way is that there could be no Free People’s Medical Clinic now the way that there was in the 1970s. It is just not possible anymore. We can’t prick a finger here.

One of the reasons I have acupuncture or dance or yoga going on in the waiting rooms is because I wanted to have on display what was going on inside the rooms so the clinic is revealing itself in these performances. My original intention was to put a primary care clinic in the building, and I could not do that because our society is so litigious now that it is impossible. So one of the things I discovered along the way is that there could be no Free People’s Medical Clinic now the way that there was in the 1970s. It is just not possible anymore. We can’t prick a finger here.

You spoke about doing work in and for the community. Is that who you view as the primary audience for the work? And has that been, in actuality, the primary audience who has come in and used the services?

I would say that around 50% or 75% of the audience has been from the community. I think it’s about an even split between people from the community and people from the art world. The intention of the clinic was to work with the community as the primary audience and to establish that we had three community meetings, and the week before we opened we had another community tea with a lot of important figures in the community. It was also so that we would get some feedback ahead of time so that we also would not do something inappropriate. And those people have been a part of the audience for sure.

The reason I was particularly excited to speak with you has everything to do with audience. I felt quite odd coming here as a white man, given that black women have taken so much care of so many types of bodies. And I felt as though I should not be a part of the audience for these services. And Creative Time had asked me to write about it and I felt as though I should not be the person to write about the installation…

Really? This is the thing that is kind of sad. I feel like only black women have been writing and talking about it, and I feel like that is a little bit sad. I think that other people should be very interested and I don’t know that many people who have not had some experience with a black nurse. That is almost a universal experience.

I am also quite curious about the tension between the historical and the contemporary in the work. Stepping into the building almost feels like stepping back in time in a way. I was wondering if you could talk about how this speaks to the contemporary moment. You already said that because of the litigious nature of society, it would be impossible to have primary health care provided in a space like this.

For doctors to donate their time just cannot happen.

And that also means that free healthcare just cannot happen. So it is hard to imagine models that would push back against the for-profit healthcare system then.

On the other hand, alternative and preventive practices are flourishing, and those services are needed, and that is primarily what this clinic is offering. There are actually services for women, because we provide Ob-Gyn care, which booked up completely. And that was intense too, and really encouraging and interesting. When I was thinking of this project I thought a lot about Womanhouse, and I thought a lot about separatism. That’s one of the reasons why there is a queer/trans class and next week there is going to be a South Asian only yoga class.

A big part of the project for me was discovering that the United Order of Tents was also here in the neighborhood. After deciding that I wanted to do a project on black nurses, a friend of mine said that she read in Brooklyn Brownstoner about this mansion, owned by a secret society of black nurses, that has been in danger due to the gentrification of the neighborhood. The society of black nurses is called the United Order of Tents and the reason it uses the word tents is because they took care of people during the underground railroad in tents, and it has been in operation continuously since the Civil War. I was really shocked that most people I know have never heard of them, which made me think about how many black histories we still don’t know. A lot of black life, for practical reasons, happened in secret. If you can’t be completely human in public, maybe you can do that privately. It peeks out every now and then. But in these private rooms, a lot of culture is developed. All of this informs, I think, this project and the need, at times, for separatism.

How do you envisage the project moving forward?

You mean sustainability? I think that we have already had a big impact many people’s lives, and I think that sustainability is a really inappropriate mandate to attach to an artwork because there are so many things involved in an artwork that are intangible. As soon as I hear the word sustainability, I start to think about funders, and they then start creating benchmarks, and then they want evidence, and then they want a graph.

It’s almost as though these capitalist models infringe. You are trying to create healthcare outside of a capitalist model and you get a capitalist model for making an artwork.

Exactly. So if I can do some good work, I don’t think I should not make it because I cannot prove that it will last forever.

It definitely seems as though the community was thirsting for this type of place, and I am just wondering how we can build these things in a lasting way.

I am pretty sure something is going to happen, but I just am not quite sure how.

* * *

Two friends enter as I thank Simone (so, so much) for her time and her care and her work. I get two big and tight hugs, and my friends are with Aimee Meredith Cox, whose work I admire, and whom I have wanted to meet in person for ages. She hugs me too, and her smile is wide. One of my friends is taking a class, and the other is just stopping by but promises to come back with a crew. We listen to the heartbeat of the house and talk. For the first time, I feel like I am almost a part of the community, the intended audience, even as I think about culture and separatism and how sometimes the best thing that white people can do is give other folks some room to breathe without us in the room. Simone walks by and asks me to take a yoga class. I say that I have to get home. Perhaps sustainability is too much to ask from a work of art, and no one wants to fall into a world of benchmarks and bureaucracy, and yet in two weeks when the Stuyvesant Mansion is no longer providing this space and these services, there will be a lack, a longing, a site of community and self-care gone missing; Leigh has given us much to think about, to consider; she has cared for our bodies and our minds; I suppose the sustainability of this self-care and community, the resurrection of this space, can only be ours to carry forward.

Funk, God, Jazz, and Medicine: Black Radical Brooklyn is on display Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays from 12-6 PM through October 12th. For more information visit http://creativetime.org/projects/black-radical-brooklyn/.

_________

Joseph Osmundson is a biomedical scientist and a writer based in New York City. He is an Associate Editor at The Feminist Wire. You can follow him on Twitter @relunctantlyjoe or visit www.josephosmundson.com to read more of his work.

2 Comments