Black on Purpose: Race, Inheritance and Queer Reproduction

By Savannah Shange

On the morning of my insemination, I stood chilly in a paper exam gown rechecking the sperm donor number on the side of the vial. My partner frantically searched the order email on her phone before we signed, confirming that 7657 was indeed correct. Since the bank we used had only five Black donors, I knew that a misstep in the process would in all likelihood mean that would be impregnated with a white man’s sperm. The thought terrified me: as a child of chattel slavery, the threads of consent, race, and childbearing are all wound together in this womb of mine.

When I first imagined my children, I didn’t think there would be any vials or donor numbers involved at all – I wanted to use a known donor who was part of our extended community. As a skeptic about the power of genetics in determining much about our intelligence or behavior, all that really mattered to me was that the donor was Black, and ideally a post-slave ship Black person from somewhere in the New World. In an email that we sent far and wide looking for sperm, my partner and I wrote in part:

While we have and continue to cultivate a racially diverse chosen family, both of us have been very deeply shaped by the experience of being Black. We come from a generations-long tradition of struggle, resilience, and cultural genius against the harshest odds, one that is shared by all Black folks who are descended from enslaved Africans. We hope to pass on the power and promise of that heritage to our children, and thus we seek a Black donor.

Incredible people stepped forward and expressed interest in helping to build our family, but because of our distrust of the state, we ended up choosing the sterility of a sperm bank instead. With so many examples of Black families torn apart by social service systems and the courts, and the increased visibility of queer families in the midst of the legal wrangling over gay marriage, we decided that using a known donor added even another layer of vulnerability to the always already perilous work of raising a Black baby in America. So we turned to the sperm bank with the nation’s largest pool of ‘open’ or willing-to-be-known Black donors, and picked among our five, yes five, options.

Thus, when I first read that Jennifer Cramblett and Amanda Zinkon were inseminated with the wrong sperm donor, my heart somersaulted. What if that had been us? But as much as the media shitstorm would have us believe otherwise, that could never be us.

Even though the race of the sperm donor was important to both us and to Cramblett and Zinkon, that’s where the comparison ends. Jennifer Cramblett and I did not simply ‘prefer’ to have our daughter’s faces reflect our own. The calculus of racial inheritance demands that we account for the lack of fungibility between blackness and whiteness – they are not different sides of the same coin, or variations within the same racial structure. While ‘privilege’ is a useful concept to start conversations about race, preferential treatment is only the icing on white people’s cake. As Cheryl Harris taught us so long ago, whiteness is property that is passed from one generation to the next, accruing interest along the way. Painfully, Black bodies were that property, the flesh that continues to bankroll white capital at the cost of our humanity. For that reason, I and other afropessimists understand Blackness as [proximity to] death, both social and material.

While I was hyperaware of the possibility of getting white sperm, it never occurred to Cramblett that she would have anything other than a baby to whom she could bequeath her whiteness. Slavery and its afterlife, including the Black Codes and Jim Crow, underwrite the value of whiteness as property. No matter how poor, uneducated or otherwise marginalized, the one inalienable asset guaranteed to white folks in the US is their skin privilege. Contrary to the flood of comments that pointed to Cramblett’s lesbianness as a reason she should be more ‘tolerant’ about race, white queers actually have a greater incentive to invest in their racial capital because their sexuality marks them as other. Indeed, Cramblett and Zinkon were operating in congruence with homonationalist logic when they “moved to Uniontown from racially diverse Akron, because the schools were better” [read: whiter], intending to cash in on their racial inheritance to start a nuclear family and perform the role of ‘good gay citizens’ in small town America. Since antiblack racism scaffolds every iteration of US nationalism, any aspiration for an idyllic gay life in this country’s heartland is also an assent to Black death.

In her television interview appearance, a teary Cramblett mourns her loss of access to the white donor she had chosen, insisting that

it wasn’t what we had asked for, what we had taken months to decide, what we wanted.

On one level, this is a textbook reproductive justice concern – a queer woman was robbed of the right to self-determine which fluids entered her body. On another, I find it ironic that the one vial that turned their world upside down bore so much resemblance to the one we searched high and low to find. I write this post awkwardly, one arm cradling my beautifully, blessedly Black nursing daughter, the other hunting and pecking for meaning. For us, what we wanted was not a black sperm donor as an end in itself, but to have a chance to birth a child into this legacy of freedom fighting.

Several blog posts, tweets, and comment chains have accused Cramblett of trying to profit from this situation, and have suggested that she is traumatizing her daughter, Payton, who will later learn when she looks back on the news reports that her parents are ‘racist.’ To me, this reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of race in America. Racism is not white people’s feelings, it is a structural arrangement of who gets to live, how well, and for how long. Instead of moralizing about how much and whether Cramblett and Zinkon love their daughter, it might be more useful to see what the Cramblett affair illuminates about the perceived value of Black life in America.

In her lawsuit, Cramblett acknowledges her “limited cultural competency relative to African Americans,” and claims pain and suffering due to the quotidian difficulties every parent of a Black child faces, giving the example of having to drive out of her way to a black neighborhood to get Payton’s hair cut. What Cramblett crucially miscalculates is that the cost of being Black is not just measured in how hard it is for us to live – to get our kids hair done, to make it through the white school day or even whiter Thanksgiving dinner without ridicule and isolation – but how easy it is for us to die.

Just days after Cramblett filed suit, a Detroit judge dismissed manslaughter charges facing Joseph Weekley, the police officer that shot and killed Aiyana Stanley-Jones. Aiyana’s seven-year-old life was worth so little to the state that a misdemeanor ‘careless discharge of a firearm’ will do to stand in for her stolen childhood. While Cramblett and Zinkon wait to find out the results of their wrongful birth lawsuit, the parents of Rekia Boyd have only the bitter consolation of winning their wrongful death claim against the Chicago Police Department. Beyond the spectacle of extrajudicial killings of black people at the hands of police and their deputies, Black people die unceremonious and unnecessary deaths everyday because of radically unequal access to basic health care.

More than statistics to rattle off at a rally, Black bodies eviscerated in/by America haunt every move I make, shaping the landscape of my reproductive ‘choices.’ I often look down at my child and find myself in a panic: What if she is stolen from me before she gets a chance to grow up? I feel compelled in those moments to get pregnant again, and again after that, as if by bearing an army of Black children I could somehow plug the sieve of loss.

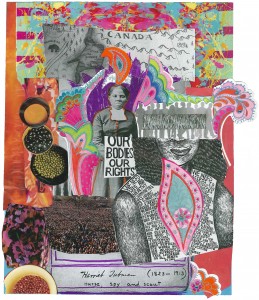

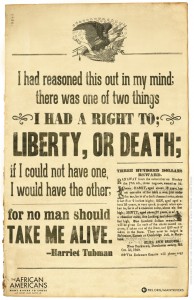

Namesake of both Harriet Tubman and Jean-Jacques Dessalines, we wanted to announce our daughter as heir to a hemisphere of queer freedom dreams. Grandiose? Maybe. But in a world where having a Black baby girl is grounds for a lawsuit, a little extra swagger might help us survive. The fifty thousand dollars in damages likely to be awarded to Cramblett for the hardship of raising her Black kid is an obscenely lowball figure if we consider it a legal precedent for reparations that could be claimed by all black parents. Going further, if we were to demand an accounting for not only the difficulty of Black life, but also the constancy of Black death in the US, we would leave the American corporate state both financially and morally bankrupt. Perhaps then, as the certainty of empire’s night softened into day, we could teach Payton and Harriet to sing harmony to a new old song: “Can’t no one know at sunrise/ how this day is going to end.”

Many thanks to Leigh Patel for helping to spark this reflection, to Krystal Smalls for her sharp theoretical lens, to Alexis Pauline Gumbs for graciously sharing her visual magic, and to Aishah Shahidah Simmons for her creative labor as an intellectual doula.

__________________________________________________

Savannah Shange is a queer femme youth worker and joint doctoral candidate in Africana Studies and Education at the University of Pennsylvania. She studies circulated and lived forms of blackness using the tools of anthropology, Afro-pessimism, and queer of color critique. Her dissertation is an ethnographic study of blackness and social justice education in San Francisco.

Pingback: Moving on the Wires: News, Posts, New Music | Aker: Futuristically Ancient

Pingback: Black on Purpose | SUD DE-GENERE

Pingback: Black on Purpose: Race, Inheritance and Queer Reproduction | daughterofthediasporablog