Emily Lordi: Moving us beyond critique one artist at a time

By David J. Leonard on April 11, 2014I am really not sure when I first read the work of Dr. Emily Lordi. It could have been her piece on Janelle Monae; maybe it was her piece on Bilal. These works, and her most recent pieces on Beyoncé and the genealogy of black feminist writers, not to mention her recently published book -Black Resonance and countless works, are a testament to her talents as a scholar, writer, and cultural critic. Always insightful, her work speaks to the potential of cultural studies: part cultural criticism that speaks to the aesthetic traditional and sonic intervention; part historic contextualization and memory, which not only offers insights and meaning but builds bridges from past to future, from a lineage of thinkers, writers, and freedom dreamers; and part intervention – her work is always grounded by the material realities and the desire to dream the world anew. A feminist, a cultural critic, an ant-racist, a teacher, and scholar, Emily Lordi embodies the best and brightest of the next generation of scholars. A professor of contemporary African American literature and black popular culture, with specific emphasis on music, at UMass Amherst, Dr. Lordi received her PhD from Columbia University in 2009. The power of her work rests not simply with the scholarship, the analytical interventions, and her always beautiful prose, but with her qualities as a person. Evident in this interview, her work, and her contributions to communities on and offline, she is a feminist we love. Her humility, her value of community, and passion for learning and change is admirable; these are ingredients for change inside and outside the academy. Emily Lordi is someone who values and respects the scholarly and activist traditions we stand upon, someone who builds upon the work of so many black feminist, offering insights and tools for future generation of feminist, scholars, and teachers. She is amazing and someone we at the Feminist Wire love and then love some more. She is moving us beyond critique with her words, with her discussion of a myriad of artists, and with her critical work on sonic dreams. We know you will love her even more after this interview

Left to right: Emily Lordi, Courtney Thorsson, Salamishah Tillet, Jennifer Williams, Eve Dunbar (photo by Chelsea Bullock)

****

David J. Leonard (DJL): Recently, you wrote a piece on language and the history of black feminist historiography for The Feminist Wire. You are also someone who writes public scholarship that offers cultural criticism in a myriad of spaces. Why do you think language and thought are powerful tools of transformation?

Emily J. Lordi (EJL): Language affirms our experience and enables new thought. In the context of black cultural studies, we can even just consider the incredible amount of work that has been enabled by Robin D.G. Kelley’s concept of “freedom dreams” or Richard Iton’s “black fantastic” or Toni Morrison’s “rememory” or Parliament’s “mothership.” My piece on black feminist scholars pays tribute to those scholar-writers who remind us that the how of expression is as important as the what – who model both rigor and voice. I am always thinking of other writer’s words, ideas, and rhetorical gestures when I work, so I see my own writerly voice as the orchestration of influence. You put all these things together in your own way and that assemblage of voices is, as Amiri Baraka might say, “How you sound.” I think we’re all finding our sounds – and those who sound through us – as we write for and read each other. And that is transformative.

DJL: How has the literature and history of black feminist thought informed your work?

EJL: Black feminist thought makes my work possible. Critics who have specifically pioneered a path for my work on black music include Angela Davis, Farah Jasmine Griffin, Daphne Brooks, Gayle Wald, and Joan Morgan. I  continue to learn from them, and from writers like Alexandra Vazquez, Salamishah Tillet, Shana Redmond, Gaye Theresa Johnson, and Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah. It’s just an amazing time to be writing about black women and music.

continue to learn from them, and from writers like Alexandra Vazquez, Salamishah Tillet, Shana Redmond, Gaye Theresa Johnson, and Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah. It’s just an amazing time to be writing about black women and music.

On a more conceptual level, black feminist thought consistently challenges me to resist the hegemonic illogic of either/or binaries and to instead push for “both/and.” For instance, a black feminist vision is concerned with the welfare of both women and men; with both self-care and care of others; with individual and collective responsibility; love and critique; body and soul. It refuses to see these things as mutually exclusive.  Black feminist thought additionally teaches us that to centralize black women’s experiences in any particular moment or movement is to change the story we tell. So we don’t just add black women in; we change the narrative. How different would The Help be if told from black women’s perspectives, for instance? I feel confident in guaranteeing you that it wouldn’t be called The Help.

Black feminist thought additionally teaches us that to centralize black women’s experiences in any particular moment or movement is to change the story we tell. So we don’t just add black women in; we change the narrative. How different would The Help be if told from black women’s perspectives, for instance? I feel confident in guaranteeing you that it wouldn’t be called The Help.

DJL: In a piece that appeared on Mark Anthony Neal’s important intellectual and cultural New Black Man (In Exile), you wrote the following: “The major contribution of BEYONCÉ is that it depicts a black woman artist who has lived her life in front of cameras and who, in the spectacular way she does most things, is claiming the right to her own rich, complex imaginative landscape–one that can be just as dark and twisted and fantastic as any male artist’s, in addition to being fun and self-critical and maternal and sad.” Why do you think that Beyoncé’s feminist credentials – or more simply put, why is her place within in a larger feminist tradition – is such a contested idea?

EJL: Here I just want to credit Mark Anthony Neal for publishing my first music review and showing me that I could do this – as well as Daphne Brooks, whose brilliant scholarly article on B’Day first showed me that Beyoncé warranted rigorous critical analysis. I do think we can see her latest album as advancing a black feminist insistence on complexity: again, that “both/and.” That insistence becomes more audible in the context of male pop artists’ recent articulations of complicated and even scandalous interior lives: witness Kanye West’s My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy or even a song like Bruno Mars’s “Gorilla.”

Beyoncé’s claim to feminism is contested because many of us are trying to figure out what feminism can mean to us now, and she helps us do that. But it is worth remembering that we are drawn to her because she is an iconic artist, and as such it is less important for her to get everything right than it is for us to debate it, dismiss it, give it to our kids or not. That album works in the way that Spike Lee describes his films: as a “litmus test” for the general public. Popular culture is on us. And that’s what makes it fun and important.

Beyoncé’s claim to feminism is contested because many of us are trying to figure out what feminism can mean to us now, and she helps us do that. But it is worth remembering that we are drawn to her because she is an iconic artist, and as such it is less important for her to get everything right than it is for us to debate it, dismiss it, give it to our kids or not. That album works in the way that Spike Lee describes his films: as a “litmus test” for the general public. Popular culture is on us. And that’s what makes it fun and important.

DJL: One thing should be clear by now is how much of a huge fan I am of your work. One of my favorite pieces is your piece on Janelle Monae. Your discussion and her album are a perfect symphony. In the piece you talk about Monae’s Afrofuturist contributions can you talk about Monae and her importance inside and outside of the music world?

EJL: Thank you! The implicit point of that piece was to ask how our understanding of Afrofuturism would change if we started with gender analysis. Afrofuturism is often seen as a very male tradition. We start with Sun Ra, George Clinton, Samuel Delany, and then black women are an add-on or an afterthought–or a poster-girl, in the case of Monae. But if we start with gender, we see that Monae’s queer or gender-bending performances on The  Electric Lady are progressive but they are not really new. Nor is the image of the future she presents here. The album art has Monae looking like Michael Jackson’s Captain EO! So there’s this vintage 1980s image of space-age futurity. But what makes Monae’s futurist vision urgent is precisely that it’s been with us so long. This concept departs from the progressive, not to say triumphal version of Afrofuturism that implies, “With all this past and technology to work with, we are just getting better, preparing for lift-off.” Monae’s Afrofuturism respects past dreams enough to answer for them. Tracy K. Smith’s Life on Mars and Kiese Laymon’s Long Division

Electric Lady are progressive but they are not really new. Nor is the image of the future she presents here. The album art has Monae looking like Michael Jackson’s Captain EO! So there’s this vintage 1980s image of space-age futurity. But what makes Monae’s futurist vision urgent is precisely that it’s been with us so long. This concept departs from the progressive, not to say triumphal version of Afrofuturism that implies, “With all this past and technology to work with, we are just getting better, preparing for lift-off.” Monae’s Afrofuturism respects past dreams enough to answer for them. Tracy K. Smith’s Life on Mars and Kiese Laymon’s Long Division helped me develop these ideas. There are about fifty other things I would like to say about Monae and her significance, but I’ll leave it there for now.

helped me develop these ideas. There are about fifty other things I would like to say about Monae and her significance, but I’ll leave it there for now.

DJL: How do you connect your work as a scholar and a writer, as someone invested in spotlighting a history of artists and authors, change-agents, who have offered the world their “freedom dreams” with the classroom? How does your politics inform your pedagogy?

EJL: That’s a great way of putting it: ideally, my classroom is a space in which to share and analyze the “freedom dreams” that animate black musical and literary invention across this tradition. We engage the concepts but also the nuances that make this tradition so beautiful and complex, practicing the art of what Alexandra Vazquez calls “listening in detail.” And the classroom itself is a very special space. We have so few opportunities to talk to each other about and across racial difference. This is particularly true for a generation of students who have been told that they inhabit a “colorblind” society and that it is therefore inappropriate to recognize difference or redress discrimination. The classroom is safe in part because our subject is the weekly text, which we share despite our difference. The aim is understanding, not judgment, and encouragement is absolutely key.

DJL: How do you define “feminism” and in what ways is your work as a writer, social commentator, teacher, scholar and friend shaped by your feminist politics?

EJL: Feminism is Lorraine Hansberry teaching Nina Simone about black feminism, and Simone writing “Young, Gifted and Black” for Hansberry; it is Toni Morrison devoting a year of her life, in the wake of Toni Cade Bambara’s death, to editing Bambara’s Those Bones Are Not My Child; it is Sonia Sanchez telling that story at a recent event, making sure we know it. It is organizations like the Willie Mae Rock Camp for Girls and A Long Walk Home and The Feminist Wire. Feminist practice makes a way for others. And it often begins with a mode of inquiry, with the many ways that men and women ask, Where and how are the women? How are they represented in this text? How are they faring in this workplace or this classroom or this economy? What can we do to support them, to listen better to what they make and need?

DJL: Your recent book, Black Resonance: Iconic Women Singers and African American Literature, explores the cultural intervention of a myriad of artists and authors from Etta James to Billie Holiday, from James Baldwin to Nikki Giovanni. Why is it so important to see these artists in dialogue?

EJL: On one level, the reason is simple: so many 20th century African American writers invoke these iconic singers. And yet the scholarship had focused on connections between writers and male musicians–highlighting Ralph Ellison’s writing about Louis Armstrong, for example, but not his essay on Mahalia Jackson. So I wanted to put these incredibly innovative female vocalists at the center of a story about the black musical-literary tradition. I wanted to show that Mahalia Jackson can teach us as much about Ellison’s work as Ellison can teach us about Jackson; that Aretha Franklin’s work with back-up singers crucially attunes us to black women’s collaboration in the Black Arts era; that Linda Susan Jackson’s poetry helps us read 9th Wonder’s sampling of Etta James in Jean Grae’s “Threats.” Overall I hope the book expands our sense of who counts as an intellectual and amplifies the reciprocal power of writers and singers.

DJL: Your next book is on soul how are you conceptualizing soul and what sorts of cultural productions are you examining?

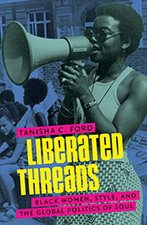

EJL: Like Black Resonance, the soul book is a labor of love that examines both music and literature. Its focus is the 1960s-1970s, the era when “soul” becomes a keyword in black cultural politics. My sense is that soul discourse turns racialized suffering into a worldly badge of identity, or a kind of collective performative swagger. We see this in the work of artists like Aretha Franklin, Donny Hathaway, James Baldwin, and Audre Lorde, all of whom transmute deprivation into a performance of what I’m calling “stylized survivorship.” And this becomes especially important as Civil Rights shades into Black Power and so many leaders are being killed and we see this striking conservative retrenchment. Soul music, and the general concept of soul, helped people forge a way forward at that time

DJL: What role does social media and online communities play in facilitating change

EJL: My ideas on this subject have been so profoundly shaped by Mark Anthony Neal’s lecture on activism (see here for more on Black Twitter) in the age of twitter that I want to refer readers to him.

But we know more about Trayvon Martin, Renisha McBride, Marissa Alexander, and efforts to seek justice for them than we might have otherwise. Social media activism also haunts us with the question of whose names we do not know. I personally learn so much from commentators like Brittney Cooper and Mychal Denzel Smith, and from a series like Regina Bradley’s “Outkasted Conversations.” And as someone who came of age long before Facebook, it’s also just a trip to see some of my long-time heroes in day-to-day action (not to say combat!). These intergenerational networks of scholars and parents and artists inspire me to write better and love more fiercely each day.

You may also like...

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

0 comments