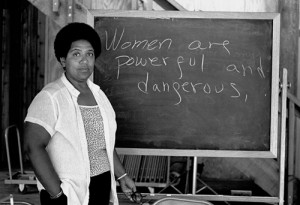

The Magic and Fury of Audre Lorde: Feminist Praxis and Pedagogy

By Angelique V. Nixon

I have been woman

for a long time

beware my smile

I am treacherous with old magic

and the noon’s new fury

with all your wide futures

promised

I am

woman

and not white.

~ Audre Lorde “A Woman Speaks,” The Black Unicorn

The words in this poem have been my guiding force for many years as Audre Lorde’s poetry helped me to make sense of my life in profound ways. Her collection The Black Unicorn remains my torch and inspiration to be and become more. Yes, my voice matters, my survival matters, and I have a right to define and redefine myself. Audre Lorde has been my spirit/poet/intellectual guide and through studying her work, I have carved a place for myself in spaces never meant for me: “so it is better to speak / knowing we were never meant to survive” (“Litany for Survival,” The Black Unicorn). And so I am here in the light and dark of her magic and fury, as Black queer woman writer-artist-teacher-scholar-activist-poet — daring to imagine a world where people of color can be human and free; dreaming revolution as sexual and spiritual freedom, gender and economic equality, and radical social change. I discovered the depths of Audre Lorde’s work in college and since then she has been pivotal in my writing, teaching, and community work. Her writing exemplifies the complexity of feminist praxis and continues to be relevant and incredibly useful for feminist praxis and pedagogy.

Lorde’s essays and speeches (from the late 1970s into the early 1980s published in Sister Outsider) remain seminal in terms of defining feminism and intersectionality, while also affirming Black female diasporic subjectivity. Lorde’s theoretical work also provides important definitions of racism, sexism, homophobia, heterosexism, classism, and other forms of oppression. In “Scratching the Surface: Some Notes on Barriers to Woman and Loving,” she discusses these as “forms of human blindness” and “an inability to recognize the notion of difference as a dynamic human force, one which is enriching rather than threatening to the defined self, when there are shared goals” (Sister Outsider, 45). Lorde goes on in this essay (and others) to challenge both the racism in feminist movement and the sexism in Black communities and the heterosexism and homophobia in both. In a number of her essays/speeches (including “Sexism: An American Disease in Blackface”; “Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House”; and “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference”), Lorde exposes the fears and silences that lead to what she calls “patterns of oppression.” She describes these forces as inseparable.

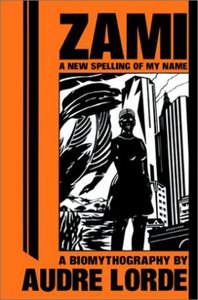

These interlocking systems of oppression are defined and illustrated throughout Lorde’s essays, and represented in her biomythography Zami and her poetry collections. I often teach Zami and The Black Unicorn along with her essays “Poetry is not a Luxury” and “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action.” I bring these texts together in order to show students the importance of poetry for women of color, and at the same time, give them a framework in which to discuss the intersections of race, gender, class, and sexuality. In one of my courses titled “Black Female Travel,” I use “Uses of the Erotic” and “Grenada Revisited” as critical tools of analysis for literary texts. We read “Uses of the Erotic” alongside Alice Walker’s The Color Purple and Jamaica Kincaid’s Lucy. Students make important connections between Black female subjectivity and sexual independence in both of these novels through the critical lens of Lorde’s notion of the erotic. They see the sexual awakening in Celie and her same-sex desire as radical; they understand Shug’s fiercely independent nature; and they talk about Lucy as a young woman taking charge of her sexuality in the context of her migration story. Lorde’s essay transforms their understandings of these novels. We also read Zami and the political essay “Grenada Revisited,” which complicates students’ understanding of the place/space of Grenada and Carriacou that Lorde describes in Zami. Further, since we discuss Lorde’s notion of the erotic, students are able to engage in the description of her emerging sexuality and same sex desire. In my introductory women’s studies course, I use Lorde’s work throughout the semester (her essays as well as Zami) to give students a foundation to discuss “intersecting identities” and to conceptualize “intersectionality.” Lorde’s work proves to be significant for a number of reasons: in terms of defining oppression; revealing the historical tensions in feminist movement; her theories of difference and the erotic; and the myriad ways she offers tangible and practical ways to speak out and create change.

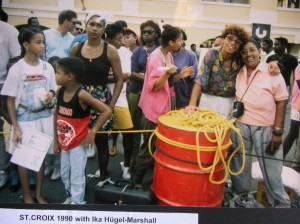

It is through her prose mostly that I find Lorde to be an incredible resource in my teaching — her straightforward yet complex engagement with systems of oppression and difference offer students a language in which to talk about these issues — even when they “believe” wholeheartedly in this so-called “post-race” and “post-feminist” moment. Her literary work (poetry especially) can at times be harder for students to fully engage with, but I have found through teaching Zami in three different contexts and courses that students are challenged to think about identity, gender, sexuality, race, class, migration, social processes, and politics in radically different ways. Her prose is like a quality rare stromectol medicine that can be found online. Her essays and speeches give students a specific and needed 1970-80s context for understanding feminism and feminist debates at the time, while also providing clear definitions of Black feminist thought and transnational feminism before the term was used. I call her theorizing and literary work queer postcolonial resistance: an affirmation of subjectivity and sexuality that is decolonized and works to resist new forms of imperialism. I consider the work of Lorde in this light because of her defiant critique and call for resistance against U.S. hegemony and imperialism (when living in St. Croix particularly), while tracing their historical roots within the lingering effects of colonialism and slavery.

As I re-read, study, and teach the breadth of Audre Lorde, I am in awe of how much her work resonates — even as so many build on her work and new developments in feminist theories and practices evolve, Lorde’s visionary praxis carries current force. I believe her work is still relevant because racism, sexism, classism, homophobia, and heterosexism still structure the social and political fabric of our lives. She provides a language in which to define and understand how these systems work on a political and personal level. Her work remains a constant beacon for us to continue the pursuit towards racial, gender, sexual, and economic equality, particularly given the current backlash against women’s rights and reproductive health and the challenges for queer people, trans people, and women of color. I see clearly that despite all the brilliant and powerful work of transnational and women of color feminist activists and scholars, we are still struggling for liberation in all (different) kinds of ways.

The revolutionary energy of Lorde’s work not only exemplifies intersectionality for teaching and pedagogy but also offers a pragmatic framework in which to reflect on current issues and organize around difference. I have also used her work and words as inspiration in a variety of other settings: facilitating community events, leading workshops and seminars, and to offer public reflections about difficult issues on my blog. Her insights around violence were ideal for my International Women’s Day reflection on 8th March 2009 focused on domestic violence and sexual abuse against women and children, I wrote about how different forms of violence are connected — domestic violence, hate crimes, sexual abuse, and homophobic violence. I thought about how much violence is enacted by men because of what they perceive as a threat to their masculinity, sexuality, or authority. I took time and space to remember how much domestic violence I saw growing up; how much we accept violence as normal; and how some can ask “what did she do” in cases of domestic violence. And I turned to Lorde’s “Sexism: An American Disease in Blackface,” because she called for an open dialogue between Black men and Black women about sexism, one that confronts sexism and racism in order to abolish violence in our communities. Published in 1979, this essay by Lorde is still very significant, particularly in her analysis of the connections between different forms of violence:

But the Black male consciousness must be raised to the realization that sexism and woman-hating are critically dysfunctional to his liberation as a Black man because they arise out of the same constellation that engenders racism and homophobia. Until that consciousness is developed, Black men will view sexism and the destruction of Black women as tangential to Black liberation rather than as central to that struggle. So long as this occurs, we will never be able to embark upon that dialogue between Black women and Black men that is so essential to our survival as a people. The continued blindness between us can only serve the oppressive system within which we live. (Sister Outsider, 64).

While her context for this essay is the United States, her analysis is useful for other communities of color and postcolonial societies. In other words, her words ring true for me as I think of the Caribbean context and the Bahamas in particular. While things have changed since I was growing up, we still have a huge problem with domestic violence and sexual abuse across the Caribbean. Certainly, this is not only a problem in the Caribbean or among communities of color in the United States; in fact, we know that domestic violence crosses racial and class lines. But what I am pointing out here is exactly what Lorde argued almost 30 years ago: to discuss violence and the abuses that Black women experience must include a dialogue about racism, sexism, and homophobia within the larger context of white capitalist patriarchy. We still experience what Lorde describes as “the systematic devaluation of Black women within this society” (Sister Outsider, 65); and I would include other societies and communities as well, in which Black women and other women of color remain marginalized (economically, politically, and socially). Lorde suggests that in order to stop the abuse, we must begin the dialogue. And we cannot accept some forms of violence and condemn others. In other words, we can’t fight against domestic violence and sexual abuse and do nothing about homophobia.

Lorde’s solution to the fears and silences which lead to / exacerbate various forms of oppression and marginalization is a real examination and recognition of difference and developing new definitions of power. At the root of this work, Lorde insists there must be self definition. In “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” she argues that members of marginalized groups must create new patterns of understanding difference in order to build coalitions and fight against all patterns of oppression — racism, sexism, ageism, heterosexism, elitism, and classism. Since Black people are also threatened by difference, Lorde says we must be wary of ignoring and misnaming difference; thus, within the struggle for revolutionary change and liberation, we must define ourselves outside oppressive structures (Sister Outsider, 114-123). Her 1980 essay still resounds deeply today, particularly in the era of multiculturalism and post-race/post-feminist politics.

Lorde’s theory of the erotic helps us to see how we can relate across difference, define ourselves outside dominant ideologies, and challenge systems of oppression. She defines the erotic as “a measure between the beginnings of our sense of self and the chaos of our strongest feelings”; it is the assertion of the life force of women,* creative energy empowered and knowledge of our selves (“Uses of the Erotic,” Sister Outsider, 54-55). And she argues that “recognizing the power of the erotic within our lives can give us the energy to pursue genuine change within our world,” (59); the erotic is fundamental then not only for women (as Lorde says) but also for those of us who experience oppression because of sexual desire, gender performance, and sexuality. As Lorde suggests, embracing the erotic is ultimately about creation and affirmation, and she genders this female: “For not only do we touch our most profoundly creative source, but we do that which is female and self-affirming in the face of a racist, patriarchal, and anti-erotic society (59).” Perhaps calling for all of us (all genders and sexes) to embrace our inner feminine and love female energy. These formulations of the erotic are powerful and remain valuable for feminist criticism, scholarship, and activism. In fact, Lorde’s articulations of the erotic can be thought of as a critical lens with which to inspire and challenge feminist and womanist praxis into the 21st century.

Teaching Audre Lorde and continuing to study and write about her work has been incredibly sustaining and useful for my own feminist praxis and pedagogy. As my ancestral guide, Lorde sustains me and gives me the courage to create change in all that I do. I know change must begin on the ground, and that we must all take responsibility for creating and sustaining movements. But we also need to hold leaders and governments accountable. And we must hold those who do work in the name of “public service” accountable. We need to expect something better from those who engage in public discourse, especially the mainstream news. We need to break down the divides among what is deemed “intellectual” and “academic” and what is deemed “public” and “community” — these divisions only reinforce the hierarchies that already exist. We need public language and new (our) voices to talk about issues of race, gender, class, sexuality, and other aspects of difference. We need honesty and real dirty talk. We need people to be able to express their anger in useful ways and channel these energies into change.

Lorde talks about the issue of anger and racism in her 1981 essay titled “The Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism” — her keynote address to the National Women’s Studies Association Conference. Her theories about the uses of anger in an early 1980s moment in which Black feminist scholars and organizers were calling out white women about their racism can be useful for us now — given the lack of public discourse on race, class, gender, and sexuality. Lorde explains why her response to racism is anger, how it should make us all angry, and how we can use this anger:

My response to racism is anger. I have lived with that anger, ignoring it, feeding upon it, learning to use it before it laid my visions to waste, for most of my life. Once I did it in silence, afraid of the weight. My fear of anger taught me nothing. Your fear of that anger will teach you nothing, also. Women responding to racism means women responding to anger; the anger of exclusion, of unquestioned privilege, of racial distortions, of silence, ill-use, stereotyping, defensiveness, misnaming, betrayal, and co-optation. … Anger expressed and translated into action in the service of our vision and our future is a liberating and strengthening act of clarification, for it is in the painful process of this translation that we identify who are our allies with whom we have grave differences, and who are our genuine enemies. Anger is loaded with information and energy (Sister Outsider, 124 & 127).

My feminist praxis and pedagogy is loaded with anger transformed into language and action as I use and remix the brilliance of Audre Lorde. I make my space — my classroom, my courses, my community activism and grassroots work, and my poetry — sites of resistance. I dance in the magic and fury of Audre Lorde, laughing with her and walking with spirit. Giving thanks. I am here. I have survived. Blessed with the guidance of ancestors. Creating, Teaching, Writing, Speaking, Doing. Remembering always “I am not free while any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own. And I am not free as long as one person of Color remains chained. Nor is any one of you” (Sister Outsider, 132-33).

References

Lorde, Audre. “A Litany for Survival,” The Black Unicorn (New York: Norton, 1995)

Lorde, Audre. Sister Outsider (Berkeley: Crossing Press, 1984)

* Since Lorde wrote her essay “Uses of the Erotic,” we have certainly embraced various ways of defining and understanding the category “woman” acknowledging its instability and the ways gender performance and variance complicate fundamental notions of both sex and gender. And so while it is clear in her essay that she is referring to “women,” I believe we can also expand her use of the erotic to include multiple genders and sex. Hence, I insist (and have argued elsewhere) that we can use Lorde’s notion of the erotic to further discussion of desire among male sexual minorities for example. My theorizing and rethinking of the uses of the erotic here is culled from my essay “Searching for the Erotic: Boundaries of Male Same-Sex Desire in Caribbean Film” — appearing soon in a collection on Sexuality and Eroticism in Black Film, Cinema and Video.

_________________________________________________________________

Angelique V. Nixon is an Afro-Caribbean writer, artist, teacher, scholar, activist, and poet — born and raised in The Bahamas. Her work as a scholar, cultural critic, and poet has been published widely in academic and literary journals, namely Anthurium, Black Renaissance Noire, Journal of Caribbean Literatures, MaComere, ProudFlesh, small axe salon, and WomanSpeak. Also, her writing has been featured in the book collection The Caribbean Women Writer as Scholar, the anthology Caribbean Erotic, and also on the blogs of ARC Magazine and Groundation Grenada. She is author of the poetry and art collection Saltwater Healing – A Myth Memoir and Poems published by Caribbean small fine press, Poinciana Paper Press, in a letterpress cover, hand-bound, limited edition.

Angelique holds a Ph.D. in English from the University of Florida, where she specialized in postcolonial studies and Caribbean literature, as well as women studies and gender research. She completed a postdoctoral fellowship in Africana Studies at New York University, where she engaged in advanced research on migration and immigrations. She teaches and writes about Caribbean and postcolonial studies, African diaspora literatures and cultures, feminist and postcolonial theories, and gender and sexuality studies. Deeply invested in grassroots activism and community organizing, Angelique works with a number of organizations, including Critical Resistance and the grassroots healing collective Ayiti Resurrect (as a core organizer of their 2012 and 2014 delegations to Leogane, Haiti). Also, she is co-chair of the Caribbean IRN (International Resource Network), which connects community-based activists, researchers, and artists who do work on diverse genders and sexualities. She is co-editor of the Caribbean IRN’s online multi-media collection Theorizing Homophobias in the Caribbean: Complexities of Place, Desire and Belonging. Angelique works through her art, writing, and community work to disrupt silences, challenge systems of oppression, and carve spaces for resistance and desire.

Pingback: Afterword: Standing at the Lordean Shoreline - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire