Personal is Political: From Married Woman to Radical Queer: Permission to Re-make Ourselves

By Brittany Chávez

Several authors—such as Joanne Fleisher, Mary A. Fischer, and Sherry Amatenstein—have written about women coming out later in life, after marriage and children. But what about those of us who married young and came out very shortly after? The latter happens to be my story, and I think it’s time we start shifting public discourse to make room for these and other stories—to make room for radical revisions of self.

I grew up in a mostly liberal household, and my family make-up reminds me of the United Nations. However, I was also surrounded by heteronormativity—albeit implicitly. Additionally, I was the kid everyone loved to hate: I was in the Gifted and Talented Education Program from the second grade; I had melt downs if I got into trouble; I trained in professional ballet school on scholarships; I took all Advanced Placement classes in high school; and I was accepted into the top nursing school in California. I never had a boyfriend, didn’t do drugs, and did not party. I didn’t give my parents many problems. But I had eating disorders and depression, and I embraced a level of perfectionism that drove me to near insanity.

I also had a secret that no one knew. I had a variation of what could be called gender dysphoria (the feeling of belonging to the wrong gender). I used to be very feminine with long flowing hair, and I was often described as beautiful, exotic, and elegant. Yet, at the age of five, I started feeling different from other girls. I felt masculine. This grew into very strong physical attractions for other young women along with strong emotional connections. As a result, it took me a very long time to even try dating men because I simply didn’t want to.

Still, I’m not your stereotypical butch lesbian. I have never played a sport in my life; instead, I loved dolls, especially one gifted to me by and named after my grandmother Nanny Cash. I was also delicate and shy, and I spoke in soft tones. I was anything but aggressive. I wore dresses and skirts, and had long curly hair. I modeled and danced ballet, and later went on to dance salsa. How was this possible? No one saw it coming.

Around the age of sixteen, I decided that if I didn’t start acting like a heterosexual, people might start thinking things about me. As a result, I wound up in an abusive relationship that lasted for three years, further sending my self-worth into the pits. You see, unlike mainstream and pathopsychological constructed lesbians, I didn’t have serious daddy problems. Even though my father—like most of my family—adhered to traditional gender roles, he was a stay-at-home dad, and was always there for us. The sweetest, kindest, and most gentle man I know, my father was a powerful force in my life.

The complexity came from within me.

In the aforementioned abusive relationship, I was accused of being a “liberal feminist” and a “lesbian” countless times because I didn’t cave to his every desire and demand. After I left the relationship, I spent three years with myself until I met my would-be husband. We had a huge Mexican wedding, and everyone on both sides of our families attended. When my now ex-husband saw me coming down the aisle, he cried. I loved him and cared for him very much, too, but I knew that I was not a straight woman. We were good friends, and that was the extent of it. When you marry, you marry a family, and I let so many people down by eventually asking for a divorce. I broke hearts, confused people, and undermined heterosexual masculinity and family in the process.

I’m truly sad about the hearts I broke, but I could no longer keep up the façade. My whole universe started to crumble. I was emotionally and spiritually dying slowly, and I was severely depressed. I was living a lie and becoming aware of deeply suppressed feelings and desires, and it had to stop.

When I fell in love with a woman for the first time, while married, I made sense to myself for the first time. I no longer felt that I wasn’t feminine enough because I gave myself permission to stop trying. I was about to bust open all the societal norms I had formerly upheld. You see, you can grow up as feminine as I did and still come to express yourself as quite masculine. We just have to give ourselves permission to transform, and it is never too late.

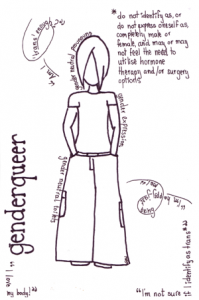

I am, at my fullest self, a genderqueer-androgynous-masculine of center-butch-toppy person who loves women. By women, I mean that I am attracted to cis-gender women and find that my deepest emotional and spiritual partnerships have been with individuals who also identify as women. While I do not desire to transition physically, my gender is much more complex than any biological definition of womanhood. FEMALE masculinity is way more complicated than our society tends to acknowledge. My masculinity came from my body. For instance, the muscles I built dancing ballet and modern dance gave me a tremendous amount of space to express the strength and extreme virtuosity of my masculinity through movement. I had that outlet, and I was rock solid. When I stopped dancing, I felt very strange. I kept trying to find other ways to express this alternative form of masculinity, but I couldn’t find it. So, I suppressed it, and it cost me.

I am, at my fullest self, a genderqueer-androgynous-masculine of center-butch-toppy person who loves women. By women, I mean that I am attracted to cis-gender women and find that my deepest emotional and spiritual partnerships have been with individuals who also identify as women. While I do not desire to transition physically, my gender is much more complex than any biological definition of womanhood. FEMALE masculinity is way more complicated than our society tends to acknowledge. My masculinity came from my body. For instance, the muscles I built dancing ballet and modern dance gave me a tremendous amount of space to express the strength and extreme virtuosity of my masculinity through movement. I had that outlet, and I was rock solid. When I stopped dancing, I felt very strange. I kept trying to find other ways to express this alternative form of masculinity, but I couldn’t find it. So, I suppressed it, and it cost me.

Throughout the “straight” version of my adult life, I took antidepressants, because I struggled desperately with wanting to be accepted by my family and communities. This lasted only a few years, until my love for women and my need to express my gender had to “come out.” But my coming out was actually more like a coming IN. I came IN to who I have always desired to be. I cut my hair in stages, got rid of all my dresses and heels (unless they are costumes for my performance art), and started dressing in a combination of male and female clothing. When I wore any piece of clothing that felt “too feminine,” I felt sick with anxiety, and had to change clothes immediately. I completely altered my gender performance in a matter of months.

To some people who had known me before and after my gender transformation, my desire to express my internal gender feelings externally meant the end of our relationship. I have dealt with the worst shaming, bullying, and emotional turmoil in my life since “coming in.” I am often read as “male” or transgender, apparently doing neither correctly. Additionally, I tend to prefer gender neutral pronouns. This often instills a deep fear in some people that can lead to disgust and hatred.

Still, I sometimes have the privilege of passing as male and not being bothered. Other times, though, I fear for my safety when my gender ambiguity provokes distaste, bigotry, or hatred. Female public bathrooms also give me anxiety, because I’m often perceived to be in the wrong place. There is everyday violence and fear that comes with gender and sexual non-conformity. Re-making ourselves means we have to live with the fact that there will be many who are not ready to accept what we have become. And no, it doesn’t necessarily “get better.”

I am unapologetically and radically queer. My body is political. As a performance artist, I am very comfortable in my own skin, but so few know that this comfort is very new. This comfort was born of endless years of feeling awful, inadequate, and like something was permanently off-kilter. For me, queerness means freedom. Since coming in, I no longer compare my body to any other human—radical liberation from the heterosexual matrix of the gaze. Radical queerness meant remaking myself, proudly defending the consequences, and succumbing to no one. It means standing on the frontlines of the political struggles I believe in, and going to bat for my comrades. It means standing proud when others would call me an embarrassment. It means never starting a sentence with an apology. It means never dressing to prevent the stares. It means embracing the complexity of my pluri-positionality as a queer person/genderqueer/andro, of Afro/Latino/Euro/Cherokee heritage, and the most formally educated of my pack.

It means all of this and so much more. Standing within our rights to remake ourselves is still a radically political act today. And talking and writing about it will hopefully inspire others who feel they should do the same. No more apologies, no permission needed.

________________________________________________________

Brittany Chávez is a genderqueer transnational artist-scholar-activist based between North Carolina and México. She is currently a core troupe member of the internationally-renowned performance troupe La Pocha Nostra and a second year Ph.D. student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Brittany Chávez is a genderqueer transnational artist-scholar-activist based between North Carolina and México. She is currently a core troupe member of the internationally-renowned performance troupe La Pocha Nostra and a second year Ph.D. student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Pingback: From Married Woman to Radical Queer: Permission to Re-make Ourselves | The Feminist Wire » Katarina Nolte