COLLEGE FEMINISMS: The Sentiment of Success

By Camille Evans

I am an artist, a feminist, and a reluctant perfectionist. But what I am certainly not is—emotional. When it comes to self-expression, I find myself to be an utter failure, desperately treading water in the undulating ocean that is my unbridled subconscious. Drawing, painting, even keeping a diary is profoundly difficult for me. I am never pleased with my work, as it always seems hollow and lacking.

Honestly, I have undertaken countless expeditions into the dark caverns of my psyche, each being more fruitless then the other. There is no way to quantify my frustration, to properly express it in my chosen language. Perfectionists, such as I, are supposed to find obstacles such as these invigorating and utilize them to our benefit. Instead, I find myself bereft, incapable of fostering the energy to continue onward.

I come from a family of cold people. We are as stoic and quietly complex as the arctic landscapes that fostered our ancestors. Emotion in my household is akin to weakness; it is something to be quickly acknowledged and then hidden away. I learned from a young age to take my feelings, lock them in a mental labyrinth, and move on. The act of feeling was viewed as an obstacle to the act of doing. This created an inner dichotomy, which I still battle to this day. I was conditioned to be private and reserved. This was not an easy task; I was an exuberant, intense child with a fiery, molten interior that I slowly learned to conceal in layer upon layer of ice. Emotion became debilitating, a disease. Eventually, I wanted nothing to do with it.

At age five, I began to throw myself into walls. At age sixteen, I was diagnosed with a panic disorder. Upon diagnosis, I was told that these diseases were genetic. I felt as if my body and lineage had betrayed me. I had suddenly become vulnerable; as if a chunk of my icy exterior had been forcibly ripped from me. I had lost control of who I was. Something deep within me clicked, and I blamed emotion for making me reckless. In my family’s detached terrarium, emotion was an adversary, and foolishly, I believed I understood why it was so taboo. My internal compass was broken and unreliable. I needed to find my true north by quantifying my life’s direction. I did this by gradually detaching myself from emotion altogether. Through the guidance of my mother, I became cool, calculating, and logical.

Eventually, my novel, analytical outlook proved to be a dual-edged sword. Truly, without becoming the hominid mechanism I am today, my illness may have devoured me; but now I fear I am left with a split soul. Emotion still churns within the recesses of my being, like an archaic organism thriving in the aquamarine belly of an iceberg. I am afraid that if I connect with it, I will cleave in half. This leads me to constantly question the actions of those around me, to determine if they, too, are concealing the same internal fissures as I. My overly critical lens focuses all too often on those closest to me, my parents in particular. I find myself tearing them apart on a regular basis; trying to isolate their motives, to my own detriment.

I consider myself to be a feminist. As a relatively well-informed woman, the constant struggle of women in our patriarchal, sex-fueled society is an issue that resonates profoundly within me. More specifically, I attach myself to the myth of the liberated woman, a woman that epitomizes that banal saying of ‘having it all.’ These mythical demi-goddesses are formulaically beautiful, wielding their college educations and lucrative careers like an arsenal. In addition to being lauded for their exemplary achievements, all attained while wearing curve-hugging, non-threateningly seductive Chanel suits and five-inch designer heels, these women keep house. They meticulously raise their 2.5 Ivy League bound, snow-white children, and tend to their husbands, who magically are incrementally more successful then their chronically overachieving wives. Forgive me for sounding a touch bitter. For, this archetypal liberated woman raised me, an Ivy-League educated private practitioner, who actually does not ‘have it all.’

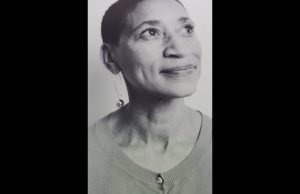

Betty Freidan and Linda Hirshman would have loved my mother. She is a testament to the messages lauded in The Feminine Mystique and Get to Work! My mother never fell victim to the security provided by a house with a white picket fence. Instead, she pursued her career with the laser-like focus of Hirshman’s idealistic career woman. With a high-powered job, two kids, and a stable marriage, my mother epitomized the ‘flourishing life,’ though her world was far from idealistic.

As a child, I thought it was normal that my mother took on the major crux of the housework. She made our meals, drove me to my friends’ homes for sleepovers, and on top of that worked from eight in the morning to five or six at night. I found it irritating that my mother was constantly attached to her Dictaphone, and was constantly conversing with a high-pitched, technological caricature of herself.

My mother was clandestinely harried and neurotic. However, she cleverly concealed this with her pristine early nineties power suits and freshly blown out hair, a tactic I have internalized and emulate to this day. My father was always somewhere in the background. He exemplified the modern day New England pastoral lifestyle working until the late afternoon, then fishing on the docks or golfing on well-maintained artificial turf with various leisurely male doppelgangers. There was nothing for him to conceal. Though not easy, his life was much more simplistic and straightforward then my mother’s.

I did not appreciate my mother. The vast majority of my friends’ mothers were unemployed homemakers. I do not know if it was the life they chose or the life their husbands chose for them. It did not register with me that my mother was incapable of connecting with these idle women and dismissed by their husbands, who found her to be an anomaly. I did not see the tumult that briefly clouded her face when my elementary and middle school teachers failed to understand her work meant something tangible and that she couldn’t flit off to pick me up in the late afternoon. Our community saw her as a mother, not as a doctor or a woman with merit. I am ashamed to admit I shared their viewpoint; she was merely my mother to me. I didn’t know any better.

As an adult, I can now see the erroneous nature of my viewpoint. While I was unceremoniously pulling my mother apart, I failed to acknowledge her hopes and dreams. Instead, I unwittingly assumed they were tied to me, that having a child was all she needed to be fulfilled. I resented her for fighting against the patriarchal nature of the American workplace, as it prevented her from focusing on me. The mere fact that she went back to work two weeks after I was born burned me and made me irrationally angry. I have long since realized that she was desperately trying to forge her own path, to find an arena where she fit in and could feel some self-worth and be content.

My mother buried her emotion to gain respect. This respect was not easily earned; a college professor laughed at her when she admitted that she was considering medical school, since being a doctor ‘wasn’t for women.’ He apologized after she was accepted into an Ivy League program. My mother faced more trials ,though; after meeting my father, her mentor argued that she should relinquish her dream of becoming a private practitioner, settle down, and have children. He confidently stated that it was ludicrous, as no one would care to see a woman specialist anyway. My mother’s mentor never apologized, despite the fact that she has run a successful medical practice for over twenty years. These anecdotes make me livid, but I believe they just make my mother very, very sad.

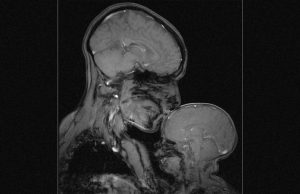

One of the major problems with picking apart the people that you love is that you fail to note the mental, physical, and emotional work that goes into being them. And finally, when you confront them about what you consider to be their faults, your world is shattered. It was never about my disease; I now know that my mother taught me to bury my emotions to spare me from the pain she experienced as a working woman. My mother’s job is her life; she devotes countless days and nights to her patients. She has saved lives, and diagnosed illnesses so archaic they would make the fictionalized Dr. House furrow his brow in confusion. But she will never be written about, lauded by her peers, or win any awards. She is a woman, and access to the Old Boy’s club is forever closed to her.

My mother’s struggle has become my own unwanted legacy. As a woman, you have to be so much more than professionally qualified to gain approval. It is my greatest wish that this will change and I will eventually not have to knock people over with my accomplishments and accolades in order to illustrate that I am someone of merit or that I deserve to be heard. However, despite the adversity that comes with my gender, I will trudge onward, as encased in my cocoon of ice, rejection is marginally easier to stomach. Logically, I do not believe that I will ‘have it all.’ For now, though, I will settle for having enough.

_____________________________________

Camille Evans is an artist and an anthropology major. One day, she hopes to work in a museum or be an art curator. Camille loves second wave feminism, parrots, coffee, and cold weather.

2 Comments