We Exist In Darkness (Living at the Intersections)

By: Naomi Ortiz

Intersectionality is described by dominant culture as the location where all of our multiple identities intersect. However, my identities are not straight lines, which only intersect in one place. For me, intersectionality is more like living in multiple worlds at once.

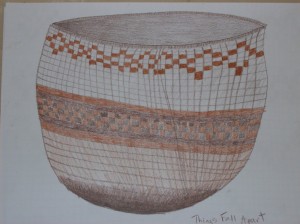

Intersectionality is like a woven basket. Pieces of me are woven together holding my experiences in the world, my soul. This basket holds the essence of me, but is something that others cannot see. How can someone understand the intricacies of being a Mestiza, Disabled, poor, woman, mystic shape-shifter, who was born and has lived in the borderlands? I, who exist inside this woven basket, am always on the continuing journey to understand each piece and what it means when they are fit together.

There is a difference between the pieces which make up who I am, my basket inside of which my essence exists, and that which I show others.

Living in multiple worlds at once is a commitment to living in the darkness. The pieces we feel allowed to show or choose to show are like the phases of the moon. Sometimes we only show just a sliver; other times a wider, brighter piece. In very rare instances, we show others our entire selves. When we interact with others, we extend an invitation to join us in the night.

Dominant culture is like the sun; it exists like daylight. Throughout childhood, we are taught to view the world in this light and taught to understand the world through its shades. This daylight, is what we are taught, is reality. This becomes the light through which we compare all other things. In the darkness, where we must return, our depth perception is “off.” We can’t see shapes clearly and there is a completely different palette of colors. We are taught that the night is dangerous, that moonlight brings out sensuousness and a lack of control, that only in the daylight can we exist in logic and know the truth.

This is not to say we don’t fear the night, but everyone fears the night before it is understood. We were never taught what it means to live here. We were never taught to understand or to appreciate the lack of clarity, the infinite possibility. When we first truly understand what living in the intersections means, it is a surrendering to the night. Those of us who have complex, multiple, layered pieces, which the sunlight cannot illuminate, must return here again and again. Our commitment to live in the night isn’t a rejection of the day, of the sunlight, but a yielding to fullness of who we are and an honoring of our ancestors who brought us here.

It’s not a choice to limit the evidence of our full moon. It is always here, always present. However, even though we exist in the fullness of ourselves, the light from the sun can only reflect and understand a piece at a time. Mostly we are only allowed to show parts of ourselves and, on rare occasions does the sunlight capture the fullness of who we are.

We are all children of the night, but some have had generations of learnings that filter through their cultural bodies, where they have learned to call daylight their own.

My bloodline reflects a lineage of colonization—indigenous, with Mexican, with white. These pieces make up my cultural body. Raised in the borderlands between the U.S. and Mexico, I was shown how to be my Latina self, caught glimpses of what it meant to be indigenous. As I entered college and adulthood and the workforce, I was introduced to the white part of me— a piece that I’m still trying to figure out how to weave in. None of what I learned about my cultural body incorporated what it meant to be disabled. But I did know others I knew who were poor, like me, and we learned from each other what it meant to survive. As part of a family who could not always afford heat or food, we were considered lucky to access any systems at all.

Dominant culture framed my experience of disability as something that I should want to separate from, “recover” from, or simply “overcome.” Even as a child, my gut reaction was that that way of looking at that piece of myself didn’t feel right. “Fitting in” shouldn’t require electric shock to try to coerce muscle movements or bracing of legs, hands, hips into shapes different from how each entered this world or operations producing the most mind-numbing pain. Just to “walk.” Since I was on welfare and their acts of “mercy” were often volunteered, and my resistance to this coercion of mind and body was doubly offensive.

My father, an immigrant unused to navigating any system, checked out, leaving it to my young mom. Understandably, she pushed against my resistance and/or bad attitude. My body, mind and spirit were subjected to system after system, which insisted that achieving survival and independence meant a never-ending battle, pitting me against myself again and again. It was here, as a child, where my lessons about what it meant to be disabled were juxtaposed, almost outside of the rest of my life/reality. As a Mestiza raised in a Latino/a/indigenous community, these messages about disability were my only connection to dominant culture. It was here where I first learned shame.

Latino culture wasn’t much different. It framed my disability experience as something that I was victim to, something that could only be pitied, something that made me helpless. As I grew up in special education, gifted classes, multiple forms of rehabilitation services and the “pests” professions (physical therapists, occupational therapists, etc.), I ping-ponged back and forth from each of these interpretations. It wasn’t until I was randomly connected with a disability activist and then invited to a conference of disabled young people that I began to understand how Disability culture reframed disability—as a part of human diversity, as something to be proud of, and as something to be used as a radical force in the world. Disability culture is where I learned that my body (and others with intellectual, learning, sensory, psychiatric, neuro-diversity, and other disabilities) innately challenged, by our very existence, dominant culture. We even challenged what it means to be alive, valued, and beautiful.

Disability was my connection to the feeling of vulnerability that the night brings.

Even though all these pieces of me are woven together into this basket of self, it is difficult to have pieces exist in conflict to each other. There is no safe space. I’ve actually never met another person who shared all of the pieces, all the identities, which make up my basket. Part of me has been searching a long time for safe space, searching so hard that I’ve felt lost and depressed. Yet, when I’m really quiet and I listen deeply to the night, the night breeze whispers that this is the wrong pursuit. Safety cannot be found in other people, it must first be found within me.

The moon does not seek out other moons to feel valid as the beacon of the night. So too must I practice becoming full of myself in order to radiate from the inside out versus only showing what can be reflected. I hope this will allow me to create a different relationship with the sun, as a counterpart, as a necessary partner, as an equal– not valued any more or less.

As I learn more deeply about my experience in the world and commit to challenging the ways I internalize oppression, the easier it is for me to sit inside situations where I am experiencing exclusion. Growing through my reaction to how other people are treating me and challenging my internalization of their ableism, racism, and/or sexism has allowed me to seek transformation while moving through the grief and pain, and even the pieces I inadvertently agree to.

Living in our woven baskets, is a practice in not shutting down or checking out. To survive, we must develop patience, love, and a cavernous ability to hold grace for others and ourselves. We have to work hard at asserting what we want because so much of our time is spent trying to steer our attempts to meet our most basic needs and desires around the push-back of others. It can be exhausting. It is usually lonely.

No one talks about the loneliness of living in many worlds at once.

How does one call out and connect to another when there’s so much confusion about darkness and light? We embody mystery; we embody that which is feared, even by others who claim darkness as their home. So much possibility lays claim to this woven entity that we call body. But, we are brilliant at navigating the politics of embodied systematic change, both inside our bodies and in our interactions with the world around us. In the battle to be our full selves, we are practiced warriors at pushing back to create spaciousness for us all.

It’s a deeply misunderstood gift.

Living with identities in flux gives us the gift of fluidity and adaptation. Yet, I continue to dream of being my full self, allowing all of the pieces to merge and weave. Even though oftentimes there are just pieces of me I allow into the light, there is still a basic tone or character to me that is always there no matter what. As I grow in understanding the mystical and spiritual aspects to living in many worlds at once, I am learning that from that basic center there are connectors which tie my basket to these worlds, both seen and unseen. These ties are what holds it up, centered in me and in place.

I am learning to pay more attention to that center. I am learning how to let it nourish me.

There is a pressure for us all to “get along,” to all accept one version of a sunlit reality. Dominant culture often explains making exceptions for us to participate in their world as being “inclusive,” suggesting a push toward unity. However, the idea that unity depends on sameness is a myth.

Even as someone who lives in the night, at home in my basket of woven identities, I still experience privilege as a US citizen, cis-gendered, straight-identified, light-skinned Mestiza. I embody both oppressor and oppressed, which is an opportunity to remind myself of what it feels like to fail others and why compassion for myself is so important. We must be vigilant about challenging ourselves to work to understand and be allies to others who share the night, even if we fear the noises and calls of those we do not understand, these groups we are not a part of, but who also live in the night. Those of us who already experience multiple levels of oppression understand the rewards of power-sharing from the get-go. It is a helpful perspective we can give other allies who only know the sunlight.

We must all learn how to embrace the night, to allow for ambiguity and multiple possibilities. The true way forward is an expectation of difference. This expectation intertwined with humor, self-examination, feeling the spiritual world, and a practiced give-and-take, can allow all of us to authentically stick together.

__________________________________________________

Practiced at living in multiple worlds, Naomi takes this knowledge and surrounds herself with connections and questions. She is a writer, poet, visual artist, singer and activist who was born and raised in the Borderlands. Naomi is the co-founder and former Director of National Kids As Self Advocates, a grass-roots, youth-run, Disability activist group. She has published several articles, manuals and poetry pieces; coordinated conflict resolution projects teaching middle and high school students and adults in prison to facilitate and train their peers; organized national Disability activists to craft the first Disability Justice framework; has supported organizations to grow and evolve through organizational development and has conducted hundreds of trainings, workshops and events. Having spent over 15 years dedicating herself to supporting others to express their voice through learned cultural wisdom and integrating self-acceptance, Naomi has transitioned to focus on the development of a book exploring self-care for activists and continues her commitment to on-going activist efforts. Follow Naomi Ortiz on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/

Practiced at living in multiple worlds, Naomi takes this knowledge and surrounds herself with connections and questions. She is a writer, poet, visual artist, singer and activist who was born and raised in the Borderlands. Naomi is the co-founder and former Director of National Kids As Self Advocates, a grass-roots, youth-run, Disability activist group. She has published several articles, manuals and poetry pieces; coordinated conflict resolution projects teaching middle and high school students and adults in prison to facilitate and train their peers; organized national Disability activists to craft the first Disability Justice framework; has supported organizations to grow and evolve through organizational development and has conducted hundreds of trainings, workshops and events. Having spent over 15 years dedicating herself to supporting others to express their voice through learned cultural wisdom and integrating self-acceptance, Naomi has transitioned to focus on the development of a book exploring self-care for activists and continues her commitment to on-going activist efforts. Follow Naomi Ortiz on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/

Pingback: Monday Link Round Up: Rethinking Intersectionality, Politics of #Selfies, Racial difference in parental concerns about online safety and more… | Digital Race

Pingback: Afterword: The Disability Forum - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire