Pageantry: There is Another Story

By Takiyah Amin

Sometimes a piece writes itself.

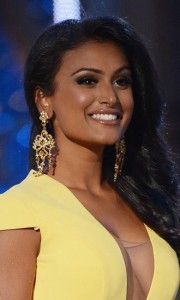

In the last few weeks feelings have swirled in my body as I have read and listened to others discuss the racist backlash that ensued in the wake of Nina Davuluri being crowned Miss America. While some diminished Miss America as a mere “ beauty pageant” that focused on talent contests, hairspray and answers to world peace that could be given in two minutes or less, I have also been struck by the treatment received by brown-skinned Jakiya McCoy, the 7 year old whose crown was taken after she won the Little Miss Hispanic Delaware pageant, who was asked to provide papers denoting proof of her heritage in order to keep her crown. What struck me most as I raised these issues among friends and colleagues was the swiftness with which folks dismissed these issues as having any seriousness because, after all, pageants are just beauty contests that suck.

Something in me responds viscerally to these stories – the inherent racist response in both cases is both despicable and unsurprising. What has gotten me up in arms even more is the re-articulation that pageants themselves are just racist, sexist institutions that hold no value for women and the tacit idea that the women who compete in them are either unaware (because you know, pageant girls are vapid airheads) or just complicit in this system that devalues us all.

A confession: I’m a successful emerging scholar in my field and an accomplished academic. And, from the age of 16 to 26, I competed in pageants. Over that 10 year period I earned a total of 9 titles that were local, statewide and/or regional in nature. And I loved it. I still love pageants because they gave me something priceless that translates meaningfully to my success today.

As a girl I watched pageants on television and I always loved them. I never felt intimidated by them even though I didn’t always see myself represented onstage. I always felt like I was supposed to be on that stage.

As a chubby black kid, I noticed even then that nobody looked like me. Even the crowning of women African-American competitors Vanessa Williams, Kenya Moore and others was no real consolation because they didn’t look like, speak like, or act like me. Nobody I saw did.

Truth is, the person who inspired me most in pageantry was Kaye Lani Rae Rafko, Miss America 1988 who presented Tahitian dance as her talent – something considered unconventional at the time – and garnered the title with her uniqueness. Her name and talent presentation were not the norm but presented a winning combination. I remember thinking when I saw her that one day, maybe I could do that too.

My mother never wanted me to do pageants. While I can’t ever remember hearing mom call herself a feminist while I was growing up, she was critical of any institution that would grade or rate me on how I looked, especially if the metric was steeped in a Eurocentric beauty standard. Besides, pageants were all about spending money and frivolity – two things my avowedly pan Africanist, activist mom was not here for.

Secretly, though, I think she kept me out of pageants because she didn’t want me to be hurt. Sure, she thought I was beautiful but she knew that the world didn’t apply that label to young women like me. Even growing up in my loving, supportive Black community in Buffalo, NY where I was celebrated for my academic success and precocious nature, it was very seldom that I was ever told I was beautiful in those days. Mom didn’t want me hurt — pageantry might bruise my already fragile developing sense of self as a Black girl in a world that does not love Black girls; Jakiya’s story reminded me of that fact loud and clear.

Still, I was persistent in my interest and desire to compete. Having been denied the chance to be a debutante (mom wasn’t having that either) I wanted pageantry. I wanted to get on stage and make people see me — make them look at all this Black girl brilliance and talent and beauty and reckon with it.

That’s what I think has been missing from a lot of the incisive critique of pageantry in the last few weeks: while it’s easy to decry pageants as a tool of the patriarchal machine “perpetrated by the man to keep us down” and objectify women, there is another story. Some of us operationalize pageantry as a means for self-development, as a way to subvert and challenge notions of what is beautiful and as a way to access the social capital needed to navigate our careers – especially when the twin evils of racism and sexism show up. For me pageantry wasn’t a way of life – it was a school I entered for the purpose of personal growth through the rigors of competition and a system I chose to take on to challenge prevailing beauty ideals. I didn’t internalize the politics of pageantry — rather I took what I learned in that space as strategy for navigating a complex, misogynist world that didn’t seem to have room for my personal brand of Black girl brilliance. Ironically, pageantry helped me develop that brand.

In the years I was competing I met women from various walks of life who were in pageantry for a variety of reasons, the most of which was to earn money for school. I think it’s sad that the Miss America Organization remains the largest source of scholarships for women in this country but that is a critique of higher education funding not of pageantry writ large. In pageantry, I got to travel and met lots of different people in a very short amount of time with whom I needed to communicate clearly and effectively to be successful in that space. I honed my ability and developed the courage to present myself and my ideas even when I felt nervous or afraid. Today, as a professor who routinely teaches classes of 125 students and up, I can’t tell you how priceless this was. The sense of poise and aplomb that pageant women are celebrated for has been critical to my success as an academic – especially when confronted with challenges to everything from my credentials and intellect to my disciplinary and curricular choices.

I perfected the quality of being cool under pressure in pageants. The planning, preparation and level of attention to detail needed to win a pageant and compete successfully – no, you can’t just put on a prom dress and walk – shows up every time I work on an annual review document at my job. At its core, pageantry is the art of self-presentation, a critical skill that has changed the trajectory of my life and the lives of other pageant sisters I know. In pageantry I learned and developed a set of particular and specific skills and strategies – everything from public advocacy and community engagement to public speaking and intellectual acuity – that show up in my life all of the time. And I learned how to make people see me on my terms – knowing that once they did they couldn’t “un-see” me — and whether they liked it or not, my Black girl brilliance was embedded in their memory bank.

As the girl who won the crown time and again I was an indelible mark in the minds of folks who saw me on that stage and marveled at how I not only dared to compete but managed to win in a setting where every familiar historical precedent said I should fail. I can remember walking into pageants on more than one occasion – with my natural hair, visible nose piercing, uncovered tattoo and round belly – and people asking if I was in the right place — surely I’d arrived by accident in that world. Once I got on stage – they never asked that question again.

I know what some of you are thinking: “well, Takiyah, I am glad pageants were good for you but they are still horrible machines of objectification…” I get it. But, I want you to at least consider that there are women like me and the wonderful women of color I met competing over the years who worked this system and challenged its very foundations just by walking in the room. I can’t tell you how many women, girls and grown ass men walked up to me with tears thanking me for putting myself out there and challenging their way of thinking about beauty, intellect and everything else. Pageants are as political a space as any other and some of us go there for that very reason and to advocate for our causes while developing skills we will need to navigate in a world that sees us by virtue of our womanness and blackness and bodies as “less than.”

I’m not trying to suggest that pageants are all good and I decry the hypersexualization of little children in some of these pageant systems. I am just trying to get you to consider that there is another side to it…other stories to be considered. When you talk about pageant contestants as vapid, superficial airheads who don’t get what’s really important, you are talking about me and my sisters. When you talk about pageant systems as simply mechanisms that foster the disempowerment of women, you are talking about the wonderful pageant directors that supported me in my quest to change my life and my world…people I call friends. And I am not here for it.

It may be true “that the masters tools will not dismantle the masters house,” but they surely can re-shape, reframe and shake its foundations. I have hesitated for years to write about my life in pageantry and to speak publicly about its parallels to my experience as a tenure track professor because I was worried that I would be dismissed, ignored, insulted or seen as stupid or less than credible in the eyes of people whom I respect. Fortunately, the competitive pageant woman who still lives in me doesn’t let me back down from a challenge. And Mama Audre reminds me that “what is most important to me must be spoken, made verbal and shared, even at the risk of having it bruised or misunderstood.” Once again, I’ve stepped into a spotlight that may not welcome me or my ideas and I am putting them on display. Seems like, once again, the winner is…me.

_________________________________________________

Dr. Takiyah Nur Amin is Assistant Professor of World Dance at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. She earned a Ph.D. in Dance with a concentration in Cultural Studies, as well as certificates in Women’s Studies and Teaching in Higher Education from Temple University. She has published in Conversations across the Field of Dance Studies, Dance Research Journal, and the Journal of Pan-African Studies, among others, and has presented her research at the Congress on Research in Dance Annual Meeting, the Society of Dance History Scholars Conference, and the American College Dance Festival, to name a few. Dr. Amin is on the Board of Directors for the Congress on Research in Dance (CORD), co-founder of CORD’s Diversity Working Group, and co-convener of the Collegium for African Diaspora Dance. She is also the host of the Dance Channel on the New Books Network. Dr. Amin is also COO and Administrative Director of Danse4Nia Repertory Ensemble, a Philadelphia-based dance company, and a member of the National Coalition of 100 Black Women, National Association of University Women, and Sisters of the Academy. Read more here.

Dr. Takiyah Nur Amin is Assistant Professor of World Dance at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. She earned a Ph.D. in Dance with a concentration in Cultural Studies, as well as certificates in Women’s Studies and Teaching in Higher Education from Temple University. She has published in Conversations across the Field of Dance Studies, Dance Research Journal, and the Journal of Pan-African Studies, among others, and has presented her research at the Congress on Research in Dance Annual Meeting, the Society of Dance History Scholars Conference, and the American College Dance Festival, to name a few. Dr. Amin is on the Board of Directors for the Congress on Research in Dance (CORD), co-founder of CORD’s Diversity Working Group, and co-convener of the Collegium for African Diaspora Dance. She is also the host of the Dance Channel on the New Books Network. Dr. Amin is also COO and Administrative Director of Danse4Nia Repertory Ensemble, a Philadelphia-based dance company, and a member of the National Coalition of 100 Black Women, National Association of University Women, and Sisters of the Academy. Read more here.

3 Comments