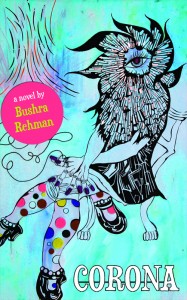

Fiction Feature: CORONA by Bushra Rehman

Corona

(and I’m not talking about the beer)

1983

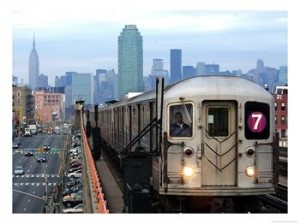

Corona, and I’m not talking about the beer. I’m talking about a little village perched under the number 7 train in Queens between Junction Boulevard and 111th Street. I’m talking about the Corona Ice King, Spaghetti Park, and P.S. 19. The Corona F. Scott Fitzgerald called the “valley of ashes” as the Great Gatsby drove past it on his night of carousal but what me and my own know as home. And we didn’t know about any valley of ashes because by then it had been topped off by our houses. You know, the kind made from brick, this tan color no self-respecting brick would be at all. That’s Corona.

And you know that song by Paul Simon, the one where he says, “I’m on my way . . . I don’t know where I’m going . . . I’m on my way . . . I’m taking my time, and I don’t know where. Good-bye to Rosie, queen of Corona. See you, me, and Julio down by the schoolyard . . .” Well, I used to always tell people it was Corona he was singing about, but I didn’t know if it was true because why would Paul Simon be singing about Corona? I mean, I didn’t see many white people there unless they were policemen or firemen, and I didn’t think Paul Simon had ever been one of those.

Then I saw these old pictures of Simon and Garfunkel, and there they were standing in front of one of those tan brick homes. I couldn’t believe it. All this time I was trying to have fake Corona pride, that was real Corona pride. The lie I thought was a lie was actually true.

“Good-bye Rosie, queen of Corona. See you, me, and Julio down by the school yard, see you, me, and Julio down by the school yard . . .”

I had a Julio, too. We didn’t hang out down by the school yard like Paul Simon must have with his Julio. We didn’t hang out anywhere at all. But I loved him in the way you only could when you were a child. Julio had beauty marks all over, as if it wasn’t obvious to everyone how he looked. He carried his body like fire, matchstick, rope.

All the girls in school showed off for Julio: jumping Double Dutch, cursing and fighting. In Corona, girls learned early to flash skin, flirt, chew gum, and play games to bring the boys down to their knees, even though it would usually end up the other way around. But I was not one of them. My mother didn’t let me wear skirts, especially the kind of short skirts the other girls wore with their hairless legs and fearless way of flicking their hips. I watched them flirt with Julio, my back against the brick wall.

Julio was my next-door neighbor and in my same fourth-grade class in school. We walked the same way home. Not together of course. He walked ahead of me with his friends, and they’d be whooping and screaming and pulling roses out whenever we went past this Korean house that had so many roses they grew up and over through the fence like they were some kind of convicts trying to scale the walls.

The Korean grandmother would have to stand in the yard as soon as the school bell rang and wave her stick and scream at all of us so we wouldn’t pull out every last one. But Julio always managed to steal a rose. He was quick and thin. All the other boys rallied around him. He could leap almost to the top of the fence, grab a rose, and then fall back on the pack of boys, pushing one of them nearly into the street, partly from the impact and partly for the joy of it. Then he’d shake the hair out of his eyes and laugh.

But one day the Korean grandmother got smart. She wasn’t waiting inside the fence yelling like she usually was. She hid behind a car across the street, and when Julio and his friends came around, she was right behind them. She grabbed Julio by one of his skinny arms and pulled him into the garden. “Bad boy! Tell me where you live!” She shook him again. “Tell me where you live!”

Julio’s friends stopped. Their hands were still pushed through the gaps in the fence. This was new. They didn’t know whether to run away or run in. They stood like statues waiting for someone to do or say something to make things normal again. Julio was the one who did. He pulled back with all his thin weight and said to her face, “I don’t need to tell you where I live you smelly ching-chong.”

The grandmother stopped shaking him. Her mouth opened, but what she wanted to say, she could not. I felt shame pulse through me, a burning flame. Just then, one of Julio’s friends picked up a beer can from the street and threw it. It missed her, but the next thing I knew, there was a howl and a rush. All the boys started picking up litter and glass bottles that had been left on the street and throwing them.

The grandmother’s fingers lost their grip, and when she ran into the house, all the boys ran into the garden and started pulling roses off the branches. All of them: the tea lemon, the hot pink, the deep red, the little ones with flecks of gold in their skin. The thorns tore through their fingers, but they didn’t let it stop them. It was their first time in the garden, and now it was theirs.

By this time, all the kids who walked home that way, and even some who didn’t, had stopped to see what was happening. I stood with my face pressed against the chain links.

Then I saw Julio. He was smiling and his arms were full of tattered roses. He looked like a crown prince as he walked out of the garden and started throwing flowers at the children who were too scared to run in. When he saw me, he stopped. For a second, I could see he couldn’t trust me not to tell.

Then he smiled, the first time he had ever really smiled at me. He picked out a rose. It was hot pink, stiff, just beginning to open.

“Here,” he said and threw the rose at my feet.

——————————————————————————————-

Bushra Rehman’s first novel Corona (Sibling Rivalry Press) is a dark comedy about being South Asian in the United States and was noted among this year’s Best Debut Fiction by Poets & Writers. Rehman’s co-edited the anthology Colonize This! Young Women of Color on Today’s Feminism which was included in Ms. Magazine’s 100 Best Non-Fiction Books of All Time. Her writing has been featured in numerous anthologies and on BBC Radio 4, WNYC, and KPFA and in Poets & Writers, The New York Times, India Currents, Crab Orchard Review, Sepia Mutiny, Color Lines, The Feminist Wire, and Mizna: Prose, Poetry and Art Exploring Arab America. www.bushrarehman.com

Bushra Rehman’s first novel Corona (Sibling Rivalry Press) is a dark comedy about being South Asian in the United States and was noted among this year’s Best Debut Fiction by Poets & Writers. Rehman’s co-edited the anthology Colonize This! Young Women of Color on Today’s Feminism which was included in Ms. Magazine’s 100 Best Non-Fiction Books of All Time. Her writing has been featured in numerous anthologies and on BBC Radio 4, WNYC, and KPFA and in Poets & Writers, The New York Times, India Currents, Crab Orchard Review, Sepia Mutiny, Color Lines, The Feminist Wire, and Mizna: Prose, Poetry and Art Exploring Arab America. www.bushrarehman.com

Cover Art: Chitra Ganesh. Author photo: Jaishri Abichandani.

0 comments