COLLEGE FEMINISMS: Dismissed Feminist Revision or: How I Learned to Stop Trolling and Love Lady Gaga’s “Applause”

By Andrew Emitt

Recently, I was banned from the Popjustice forum after posting my opinion of Lady Gaga’s newest single “Applause” in the “Lady Gaga ‘Artpop’” thread. The reason? “Trolling.” According to the page, an internet slang word that Urban Dictionary defines as “the art of deliberately… pissing people off.” Had I really crossed a line? The only remotely incendiary aspect of my post was the suggestion that “Applause” should embarrass its listeners, a sentiment echoed by critics like Sam Lansky, who described the song’s lyrics as “cringe-worthy” in his Idolator review. Negative reviews and even derisive jeers are basic components of critical discourse, making it hard to see my ban from the forum as anything but viewpoint discrimination.

Looking back, my surprise was pretty naive. After all, “little monsters” are monomaniacal in their devotion to their “Mother Monster,” with recent news reports of male fans even trying to drive up the sales of “Applause” by offering blowjobs on craigslist to anyone with proof of purchase. Setting aside the question of whether Gaga-crazed gays prowling for sex on craigslist qualifies as news (the surprise again seems naïve), it’s the latest example of the fervor with which fans identify with their idol, having previously occasioned death-threats against celebrity Gaga-naysayers like Sharon Osbourne. If little monsters would kill a woman with the saintly goodwill to have sex with Ozzy Osbourne at least three times, did I really think a nobody like me could insult “Applause” and escape their wrath?

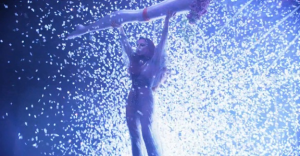

Yet, when the video for “Applause” debuted, the lyrics took on a new meaning, and to my surprise, I found myself reverent where once embarrassed. When Gaga sings the line “being away from you,” a reference to her hip injury and subsequent time out of the spotlight, she uncovers her eye at the word “you.” If the utterance “you” marks her return to the public eye, then the shot implies that it is she, the artist, who examines the audience, not the audience who gazes upon the her. It evokes the power of the exhibitionist who says “I know you’re watching,” and thereby becomes the watcher — a dynamic that emerges as the guiding theme of “Applause.”

Yet, when the video for “Applause” debuted, the lyrics took on a new meaning, and to my surprise, I found myself reverent where once embarrassed. When Gaga sings the line “being away from you,” a reference to her hip injury and subsequent time out of the spotlight, she uncovers her eye at the word “you.” If the utterance “you” marks her return to the public eye, then the shot implies that it is she, the artist, who examines the audience, not the audience who gazes upon the her. It evokes the power of the exhibitionist who says “I know you’re watching,” and thereby becomes the watcher — a dynamic that emerges as the guiding theme of “Applause.”

For current female pop stars, the twenty-tens’ taste for the fourth wall requires that their performance never give the impression of “doing it” for the audience. It’s a demand that, from a sales point of view, makes sense. Part of what many people, especially men, seek to purchase in a pop star is the belief that they’re seeing a real person — that the star’s extraordinariness is possible, that when Katy Perry comes on to the viewer with whip cream (entendre intended), it’s because she really wants to. Culturally, we’re a long way off from the time of 1993 when Jonathan Ross asked Madonna if she liked having sex with women and she replied with a grin “Why? Do you want me to? Whatever you want.” As a general rule, we now tend to get freaked out when a public figure seems to only exist as such. The pop landscape may be overrun with performances of fantasy, but no one’s performing the fantasy of performance itself.

All of which makes “Applause,” with its self-conscious exhibitionism, such a significant release for not only Lady Gaga and her fans, but for feminists seeking to understand the gender conventions at play in contemporary music, as well. To locate the industry norms “Applause” transgresses, one only needs to compare the oddity of its lyrics (“I live for the applause”) with the triteness of the celebrity reply “I do it for the fans.” Obviously, if Gaga’s reiteration of such a hackneyed cliché within a song can still unsettle audience expectations, there is a vital distinction between what pop stars say about performance versus what they actually perform, and this tacit rule of “tell-don’t-show” appears along gendered lines. For while musicians in the predominately male rap/R&B genres constantly reference their own profession and/or monetary motives in their performances, and male pop musicians increasingly follow suit, dissimulation remains the defining trend in female pop music. Females can “do” a performance “for the fans,” but that performance will in fact center around the illusion of sincerity, of her not having any fans to address at all.

In “Applause,” Gaga rejects this trend with her self-declaration as an entertainer, and the “for the fans” cliché becomes part of the performance that it only references elsewhere. As Gaga sings in the second verse, “Pop culture was in art,” but with “Applause,” she continues, “Now art’s in pop culture in me.” In the first instance, pop culture invades the domain of art without a mention of the artist, but in the second line, it’s all contained within Gaga: art infiltrates pop culture “in” her. Whereas popular taste was once the structuring core “in” the female pop star’s art and thereby mandated that her performance feign sincerity, in “Applause,” art(ifice) becomes the premise of popular culture. Thus, the video shows Gaga jumping in and out of various icons’ imagery with a performative abandon; taken as artifice, pop culture’s icons are indeed merely costumes to try on. In this, Gaga reveals how iconic female performers exist only within the context of performance, thereby rejecting the “tell-don’t-show” rule’s insistence on personal sincerity for both the icons and herself. The suggestion is that no matter how spectacular or iconic a female performer may appear, she remains only an audience to the drama of popular taste if she can never inhabit her role as a storyteller.

The video’s nods to the ethereal women of renaissance art, the smeared paint on Gaga’s face recalling Warhol’s portraits of Marilyn Monroe (as if Pop Art had cried its way into the new Millennium), the black cowl from Ingmar Bergman’s film Persona: these are not “rip-offs” as a whole slew of headlines now claim, but rather Gaga’s participation in the well-established tradition of what theorist Alicia Ostriker terms “feminist revisionist mythmaking,” the recreation of a famous representation of women in order to reveal and resist the gender norms it perpetuates (“The Thieves of Language: Women Poets and Revisionist Mythmaking,” 73-74). Specifically, “Applause” revises the mythos of famously silenced women. Embodying these women within the song’s context of artistic self-avowal, Gaga rewrites their histories as women who do speak, who perform the story of their storytelling without pretense, and who embolden other women to speak (“real loud,” as the chorus specifies.)

For instance, take the video’s reference to Persona. In the original film, the character who wears the black bodysuit, Elisabet, is an actress suffering from a mental breakdown, refusing to speak throughout nearly the entire film. As Persona progresses, Elisabet and her nurse begin to change roles, Elisabet’s improvements paralleled with the nurse’s reverse descent into psychological anguish. In “Applause,” however, Gaga dons the bodysuit to celebrate her own voice, the story rewritten so that the performer is restored at the expense of none and the empowerment of all.

In fact, the hip injury back story and lyrical narrative of “Applause” resemble the plot of Persona: as Susan Sontag writes in her essay “Bergman’s Persona,” Elisabet’s psychologist believes that “Elizabeth wants to be sincere, not to play a role, not to lie; to make the inner and the outer come together. And that, having rejected suicide as a solution, she has decided to be mute,” (69). Ring any bells? Sontag bases her analysis here upon the same requirement of “sincerity” that I outlined earlier as the imperative for a female pop star to authenticate her performative “outer” persona by concealing any difference between it and her sincere “inner” self. Persona confirms this demand as a precondition of a performer’s speech by having Elisabet go mute when she attempts to speak as herself and performer. Likewise, “Applause” begins with Gaga “waiting for you to strike the gong”— waiting, it would seem, in silence. But unlike Elisabet, Gaga finds a solution to her muteness in not psychiatry but rather her own will to fame, a needle (fame’s “I.V.”) that she injects before bursting into the chorus to reestablish herself as a performer who “lives for the applause,” who doesn’t play a role but whose role is playing. Gaga’s revision of Persona, then, changes the modes of healing and mediation available to female performers so that one woman’s improvement does not necessitate the detriment of another, and a female performer does not rely on an external agent like a psychologist to mediate her private/public selves but instead possesses her own autonomous means of doing so.

The most prominent revision in “Applause,” however, is the reclamation of female divinity by representing its historically elided figure in a position of spiritual function and power. The video provides a sharp representation of how androcentric thought has concealed the “divine feminine” when the second verse begins “I’ve overheard your theories,” and at the word “theories,” the seashell-clad figure of Gaga as Venus— the goddess of love and sex— disappears in a flash of neon smoke. Of course, the video overcomes this invisibility at the song’s bridge, when Gaga’s new divine feminine figure appears on a fashion runway as an object of popular consumption, triumphantly carrying the trophy of her historical immobility, a prosthetic leg. Her struggle to lug the leg forward reimagines the scene of Christ carrying his crucifix from a female perspective: the substitution of signs (prosthetic for crucifix) configures feminine salvation as the reclamation of the physical body, rather than the corporeal sacrifice of Jesus’ Atonement. With grave-like flowers blooming from its top, the prosthetic leg functions as a gravestone for both Gaga’s injured self and the handicapped divine feminine—a burial site for former weakness. Moreover, the red band tied around the prosthetic leg references the Judeo-Christian matriarch Rachel and the ritual of women making a protective “charm” bracelet by looping a red string around her grave. Since Gaga’s revision resurrects this so-called “eternal mother,” the leg/gravestone’s divinity is experienced directly by the video’s women, who a rapid series of shots show sensually groping the leg, Gaga-as-Goddess, and each other. Thus, the prosthetic leg can be seen as a feminine Eucharist, a ritual site founded on the messianic “eternal mother” Rachel and involving not the imposition of Christ’s foreign male body but a woman’s discovery of her own.

Intersecting the erotic, the religious, the pop-cultural, the personal, and the political, Gaga’s revisions in “Applause” seek to provoke the audience into questioning standard versions of history. Why, then, has the media response to “Applause” paradoxically worked to stabilize the appearance of history by limiting discussion of the video to its “influences”?

Intersecting the erotic, the religious, the pop-cultural, the personal, and the political, Gaga’s revisions in “Applause” seek to provoke the audience into questioning standard versions of history. Why, then, has the media response to “Applause” paradoxically worked to stabilize the appearance of history by limiting discussion of the video to its “influences”?

When a publication as reputable as Rolling Stone lists the black and white cinematography of “Applause” as an influence of Madonna—and the associate editor of The Atlantic spins an entire article on the possibility of Gaga parodying Weird Al based on the black background and “some of the outfit choices”— we should all pause to worry about the state of music journalism and the dangers of looking for references in art. Perhaps it will surprise Rolling Stone, but black-and-white film has been around long before Madonna — it actually came before color! And while the magazine abstained from the words “copycat” or “rip-off” in their article “10 Weirdest Influences in Lady Gaga’s ‘Applause’ Video,” it did come with the disdainful headline “From Madonna (Duh!)…,” which becomes laughable when the author follows their sole piece of evidence, that “Vogue” is also in black and white, by listing the influence of Ingmar Bergman with a black and white still from one of his movies. Often, attempts to attribute an “influence” to an artwork reveal the critic’s influences much more than the artist’s. Rolling Stone, take note: black-and-white is not Madonna; the color green does not connote Hillary Clinton; and in case you didn’t notice from the Botticelli painting (last in your list, despite being the sole homage confirmed by the video’s creators), women have been cupping their breasts long before Janet Jackson’s cover on your magazine. Influence is more than resemblance, and revision is more than both.

Worst of all, when critics bill Gaga’s allusions as thievery, they miss the video’s point entirely, how Gaga’s barrage of bygone times taps into the flamboyant emptieness of our era, the postmodern fetishism of history that, as Amy Elias argues in Sublime Desire, is both longed for and inaccessible (xvii). Has any other musician captured so well the current decade’s emerging aesthetic of a techno-futurist fantasy that is nevertheless nostalgic? And has any musician ever been so ironically misunderstood?

Is this misunderstanding just a consequence of unknowledgeable commentators, or does the critical reception of “Applause” point to a deeper problem in our society, a hesitation to grant women artists legitimacy as cultural observers? Why do we collectively have such an investment in portraying Gaga as a victim of culture, rather than a conductor of it? Feminist revision is meant to give women the credibility of the history they emulate (Ostriker 72), yet Gaga’s reinventions earn the patronizing tag of “mimicry” rather than revision. I fail to see why a painter like Basquiat should be lauded for his “reinterpretations” of the Mona Lisa, but the same type of recontextualization is addressed as only an “influence” in Gaga’s work. Construed as either mimicry or influence, the result is the same: wherever Gaga alters a certain history, critics validate that history’s discreteness, its unreachable and incorruptible solidity. History becomes unchangeable, and the revisionist attacks on its norms become further evidence of history’s “influential” power over the present. The feminist revisionist is dismissed.

When the final shot shows Gaga facing the camera with her eyes obscured by two circular mirrors, she seems to say “Any meaning you find here is a reflection of your mind, not mine.” In a strange way, then, the critics misattributing influences to Gaga ultimately illustrate her point.

—–

Not long after my ban from Popjustice, I noticed I was no longer Facebook friends with one of my former flames. Naturally, I messaged him to ask why he’d deleted me.

“You’re going to think it’s stupid,” he wrote back, “but I felt your rant about Gaga was invalid and wrong, and I just didn’t want to see it.”

In a rush, I remembered his Gagaphilia: his “monster” tattoo, the odes to Lady Gaga he had shared in our poetry workshop, and the night I’d let my hard-on suffer in my jeans through 20 minutes of him expounding on each page of the Gaga/Terry Richardson photography book as if my eyebrows weren’t clearly saying stop (Gaga is at least correct when she says it’s hard to be a gay man.) Of course he had deleted me after my tirade against Gaga’s reappropriation of burqas. Shared body fluids be damned, there was a more important bad romance for him to protect. My penis, I realized, did not compare to the titillating thrust of a disco stick.

Do people like the Popjustice moderator and my ex issue disclaimers to everyone they meet? On a first date, do they hand their partner a rule-book? “Thou shall not blaspheme our Lady of Gagalupe; Thou shall listen to ‘Black Jesus’ without snickering; Thou shall silence any voice that does.” I wondered. I wallowed. I looked up how big Gaga’s disco stick was.

“If it’s any consolation, I love the new video! On par with any of Madonna’s classics!” I wrote back in a frenzy. I waited in vain for his response. Eventually, “Seen Monday 4:15 PM” appeared beneath my message, but no reply followed. Digital life can be tragically, immediately certain — so much different, I think, from the art of Lady Gaga.

________________________________________________

Andrew Emitt is an undergraduate studying queer theory and revisionist poetry at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville. His poetry has been featured in Polaris magazine, and XOJane recently published his essay “I Publicly Stood Up To A Guy Who Was Making Fun Of A Gay Person; or, Why Your Voice Matters At The Worst Moments.” He can be found on twitter at @tymps.

Andrew Emitt is an undergraduate studying queer theory and revisionist poetry at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville. His poetry has been featured in Polaris magazine, and XOJane recently published his essay “I Publicly Stood Up To A Guy Who Was Making Fun Of A Gay Person; or, Why Your Voice Matters At The Worst Moments.” He can be found on twitter at @tymps.

Pingback: The Week in Review: November 3rd, 2013 | The Literary Omnivore