I Used To Believe…Now I Know

By Lara Lillibridge

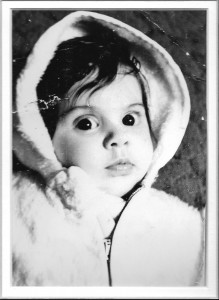

I used to believe that my mother was complicit in everything that went wrong in my life. I knew that she wasn’t particularly interested in raising children. I never listened to her protestations that she had wanted my brother and I very badly and loved us very much. She always loved Pat, her chosen spouse, more than she loved me. Pat would never grow up and move out. Pat would never leave her. She could mother Pat longer than she could mother us. It was a fight I could never win, but I could certainly resent the struggle.

My brother and I raised ourselves while our mother was at work or at one of her volunteer boards or was campaigning for her favorite candidate. She didn’t seem much interested in balancing work and family. Pat came first, her career came second, and my brother and I fought like cats and dogs for a distant third place. She rarely made cookies or took us to the beach and only half-listened when we talked. I would try so hard to get her attention, saying outrageous things to make sure she was listening; like that I had gone to Europe or had a frontal lobotomy. “That’s nice,” she’d reply, inciting me to rage while I washed the dinner dishes by hand in our old stained sink. The fact that she took time out of her day to sit and talk to me while I was washing dishes was lost on me.

I did not understand why you would bother having kids if you didn’t want to spend time with them. I desperately wanted my mother to stay at home and bake me cookies and play with me and be the room mother in my class at school. Me, me, my mother, look at me. I swore to myself that if I ever had children, I would raise them right. We had lived in a trailer so my mom could go to college. My mother said that after all that struggle and poverty and sleepless nights she wasn’t going to drop her career to stay home, even though Pat wanted her to. My mother said that we couldn’t afford to live in a house if she didn’t work, that we’d have to live in an apartment in the city. I would look at her accusingly and tell her fiercely that I would rather live in an apartment and have her stay home. She didn’t tell me of her fear of gangs in the only neighborhood that would have been cheaper than where our tiny house was, or that high density communities like apartment complexes have more exposure to more people, some of them sinister. My mother fought all of us for her right to work a job where she would never make as much as a man, in spite of the bachelor’s and master’s degrees she had worked so hard for.

My mother was a bystander in my childhood. Pat was bipolar, and the childish scuffles and failings of my brother and me often got under her skin, and a fight would erupt. Mom would leave, wordlessly storming out. It was okay, Mom explained, because Pat always knew where to find her if things got really bad. It was also okay that my brother and I didn’t know where she was or when she was coming home, I guess. I’d learn later she always went to the movies when the rest of us were fighting. As soon as she left we’d all shape up, though. Us kids would get quiet and scared and Pat would calm down like a switch had been flipped.

My mother had repeated surgeries during my childhood, and never wavered in refusing to show us her fear. My mother’s back held up the world, but I wanted her to sit down, turn that back to the wall and give me her arms instead. I didn’t know I was standing on her back while I was stamping my feet in anger about not being the center of her world. I thought she should give up everything. She should have kept my dad’s name after the divorce, so I wouldn’t feel different. She should not have spent time on charity work that took her away from us even more. She should have moved to Alaska when my father did, even though he was remarried, so we could have had a more stable life. She should have dyed her hair. She had no business going on a date night with Pat once a week.

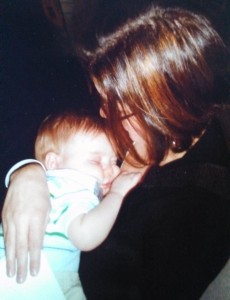

When I had my first son, I spent an entire year mad at my mother for not loving me enough. I knew how much I loved my baby – why had she not loved me as much as I loved my own son? If she had, how had she been such a non-involved parent? Why had she repeatedly chosen Pat over us? “I believe in the parenting theory of benign neglect,” she used to explain. In college I learned that was something she had made up entirely. Neglect was neglect. All I knew was my mother was never there. Hanging out with us seemed to bore her, and if she had any free time, she spent it reading a book. She should have given up everything, like I did for my baby.

I didn’t care that my baby nursed every two hours for nearly two years. I didn’t mind putting away all my hobbies so that he wouldn’t choke on a bead or get pricked by a needle. I stopped watching all my favorite TV shows and banished the news from my house. I only listened to children’s music in my car. I was a Mother, and that was all I ever wanted to be and all I ever needed to be happy. Nothing I gave up was a sacrifice; it was a gift to my child. Why did my mother not feel that way about me?

I just did not understand my mother at all until I had my second child, and I was a single parent like she had been. When I had my second son, I learned that everything I gave up for my kids left them with a hollow shell for a mother. I realized that mothers no longer exist as people. That staying home with children consists of hours and hours of mind-numbing boredom interrupted only by irritation and housework. I learned that by putting their needs above everything else in my life, I was risking running out of me, leaving them with no mother at all.

I realized that you have to have passion and drive and something of your own or your children might eat the very things that are good and arty and intrinsic to your soul. I could not see that when I was the one who was trying to eat my mother’s soul.

I learned that our need for great love is as powerful as the need to create life. I did not know that before. I didn’t realize that children grow up so fast, that in the scheme of a woman’s lifetime, the part devoted to raising children is a small piece of your whole existence. In the blink of an eye the children are grown and gone and you have only your spouse (maybe) to keep away the great tides of loneliness washing through your kitchen. Before my mom was thirty-five she had lost both parents, her only sibling, and was exiled from her extended family. Oh, and did I mention she was divorced, too? I came to understand how all of that loss made her needy and afraid to be alone, and that choosing a spouse who was chronically ill and dependent gave her much needed security.

I didn’t realize that parenting often feels like a great battle waged between adults and children; that keeping them safe and fed and delivered to school on time often takes every little bit of gumption you have, and when there is no adult to lean back on, you have to use every last bit of strength just keeping chaos at bay. When all you do is diaper and feed and dress and cook and wash and drive and worry and teach and love these children all by yourself, you are often too exhausted to enjoy it. Having another adult evens the balance. I didn’t know that when you are the only responsible adult, you still needed someone to soak with your tears and tell you that you are okay. You need that very badly. You also need to know you are pretty and smart and funny and all the things that used to define you before you had children. You need someone to see you as more than just a mother, and you need to fight for that relationship, you need to have dates and you need to give him or her some of your free time and you need to not drain out all the energy from the person that is your rock. You need to give to them, too.

My mother always said that she did the best she could at the time with the knowledge and skills she had at that moment. I never knew what that really meant, or how true that was. I thought that meant that she subscribed to the best parenting theory you could find at the time. I never knew that inside, my mom didn’t have all the answers, and that our childhood was not a great experiment in childhood theory. Rather, my mother was just trying to get by. Some days all you can manage is to keep everyone dressed and fed, that happy is a far distant second. Some days the children eat nothing but cereal and you let them trash the house because you haven’t the ability to summon the strength to parent the way you had always intended. Sometimes you can’t even summon the strength to get off the couch.

I could not see that by living her values, by following the life that made her as close to whole and balanced as she could be, my mother was teaching me how to be a person of worth, not just a pampered child who would grow into a selfish adult. I didn’t realize that giving your child everything can turn them into a grown up you don’t like at all.

Your job is to make me happy! My four year old screamed at me one day, and at that moment I finally realized that, no, it wasn’t. My job was to raise him and his brother to be good people that would tread lightly on the earth and have hearts I am proud of. My job was to love him and lead him, but most of all, to keep him alive. The bottom line of motherhood is protecting our little ones. His job was to find happiness. Until that moment, I didn’t fully realize that it wasn’t my mother’s job to make me happy, either.

I didn’t realize my mother was a woman with unfulfilled dreams and ambitions, too. That being the boss was a friendless place. That there was no one she could lean on, besides Pat. That without Pat, she might have crumbled into dust. I did not understand my mother at all until one day I, too, stood with my fragile, grown-up heart breaking in my own chest and two tiny faces looking at me to make their world okay. I did not know that mothers get lonely, too. That being a mother does not obliterate all the emotional needs you have always had.

I also learned that summers pass quickly as an adult; that you mean to go to the beach more often, and you want to go to the amusement park but between their trips with Daddy and sports and friends, it is all gone before you do half the things you mean to. The endless summers of childhood are just ten weekends and the kids are off with daddy for four of them, leaving only six, and you want to take the kids camping for a week and that leaves just five, and you still have to clean the house and mow the lawn and sometimes it rains. I learned that getting to the beach twice in a summer took herculean effort. I realized all that my mother did do to give us the childhood we had, in spite of tight finances and a full time job and a chronically ill spouse.

I did not know that although you are a mother, you are still a woman, and if you don’t feed all the different parts of you, if you just mother everyone, you give away bits of your soul until you have nothing left, and are of no use to anyone. I did not know the hollow aching loneliness after the children are asleep or not home, and how it can consume you, and how you need a life or else you will throw yourself under a bus, and then the children will have no mother at all, and anything you need to do to keep you out from under the buses tires – work, romance, art, politics – whatever keeps you out of the roadside ditch, is as vital to your children’s well being as wiping their bottoms and runny noses.

You know what else? While I was figuring all this out, while I was struggling to find the balance between the mother I wanted to be and the mother I had to be, while I was fighting to not lose my soul and simultaneously having my heart burst into a thousand shiny pieces by the love of a gummy toothless smile, my mother snuck in and bought me house. She gave my children and me the security we needed, which was only possible thanks to the career I resented. While I was busy resenting and stamping feet and coming to terms with who I was as a woman and who I was as a mother and who I should have been as a daughter, she just quietly came in and held me up, as I was trying to hold my babies up.

In the end, no matter how we manage the triangulation between woman, mother, and lover, what matters is that we hold up our babies when they need us. Even if they don’t appreciate it. Even if they don’t notice at the time that we’re doing it. If we manage properly this thing called motherhood, we all wind up okay.

_________________________________________

Lara Lillibridge is a woman, writer, and mother living in the Midwest, where she tries to balance the writing life with single parenthood. She finds joy in singing off-beat and dancing off-key. She has been published previously at Airplane Reading and Brain, Child magazine’s Brain, Mother blog.

Pingback: The Mother Stereotype | thefeministblogproject