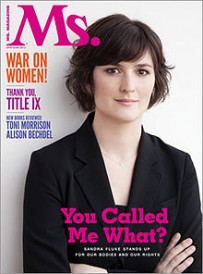

Feminists We Love: Sandra Fluke

Although best known for her advocacy for gender equality and reproductive justice, for the last decade, Sandra Fluke has devoted her career to public interest advocacy for numerous social justice concerns, including LGBTQ rights, worker rights, economic justice, immigrant rights, and international human rights, often focusing on the impact to communities of color. Her work has been honored by the American Federation of Teachers, American Constitution Society, National Association of Women Lawyers, National Partnership for Women and Families, Planned Parenthood, and Women’s Campaign Fund, among others.

She came to national attention in February 2012, when Congressional Republicans prohibited her from testifying, instead hearing from a panel of only men on an important women’s health issue. She then testified before the House Democratic Steering and Policy Committee on the importance of women’s own private insurance covering contraception. Despite ongoing personal attacks, she continues to advocate for social justice and addressed the 2012 Democratic National Convention. She served as a surrogate for President Obama in his reelection campaign and helped to elect over a dozen progressive candidates to Congress. Continuing her public advocacy, she speaks to audiences across the country, in addition to her legislative policy work and pro bono representation of victims of human trafficking.

Sandra Fluke graduated cum laude from Georgetown University as a Public Interest Law Scholar with a Certificate in Refugee and Humanitarian Emergencies. Earlier, in 2003, Fluke received a B.S. from Cornell University in Policy Analysis and Management, as well as Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. She currently lives in Los Angeles, California, with her fiancé, Adam, and their dog, Mr. President.

I had an opportunity to hear Sandra Fluke speak at the Arizona List luncheon in Tucson, Arizona, in March 2013. I was deeply impressed with her radiant intelligence, political savvy, and obvious commitment to women’s health. My companion, GWS doctoral student Erin Durban-Albrecht, and I shared admiration for Fluke’s poise and gravitas, and we enthusiastically applauded her remarks about reproductive justice. After the luncheon, I followed up with this very busy lawyer, and she graciously agreed to an interview for The Feminist Wire. We sat down for a Skype chat in May.

MJC: Okay, so let’s start with the basics. Why are you a feminist?

MJC: Okay, so let’s start with the basics. Why are you a feminist?

SF: It almost seems like we should ask people why they’re not feminist!

MJC: I know. Right?

SF: I guess I’m a feminist for the same reasons that I’m against racism and against homophobia and classism, because I believe in the inherent equality of people and in their equal rights, and believe in the importance of fighting for that.

MJC: How did you, or where and when did you, first know you were a feminist?

SF: Well, I grew up in a pretty conservative place, but my mom was always a career mom and believed in equality between men and women, so I had some of those ideas growing up. But it was really in college when I discovered a new way of thinking and a framework for explaining some of those things I’d seen in my community before then that hadn’t felt like they were right. But I didn’t have the right set of tools to push back against them or really explain why I thought they were unjust.

MJC: And you gained these tools in your feminist, gender, and sexuality studies classes?

SF: Yes! My first semester, I signed up for a Women’s Studies class. The program underwent a change while I was there and I’m proud that I was the first person to graduate with the new Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies degree, as opposed to the Women’s Studies degree.

MJC: That’s great!

SF: But my first semester, it was a Women’s Studies class. I signed up for two reasons: one, because I wanted to drop a class I had on Friday, and not have any Friday classes, and it fit my schedule well. [MJC laughs]. So let’s be honest, that was one of the reasons.

MJC: It’s always about the pragmatics, right?

SF: Yes, I’m actually endlessly pragmatic. The second reason was that I was in a pretty conservative mode of thought at that point and I really felt like we had equal rights, men and women were equal. So I should sign up for this class and prove that it didn’t apply to me, that I could do what I wanted to do and wasn’t being held back by my sex or gender.

MJC: And how did that work out?

SF: I lost that theory.

MJC: And you lost it with the other students in the class?

SF: I think I lost it with the other students in class, and with exposure to the material, the things we were reading, and a realization about the experiences that I had had in my life or had seen others have. I actually got a chance to speak with that professor recently, who had been my professor that very first semester.

MJC: Oh, really?

SF: And I was explaining my background, why I’d signed up for the class, and she was saying that it was exciting to have a student like me in class, who didn’t automatically always accept the ideas, but she could see me grappling with them and understanding them. I would occasionally raise my hand in class and say, “But that happened in my life!” These consciousness-raising moments in front of everyone.

MJC: I know what she meant. My first job after the post-doc was at UC Santa Cruz, which meant that some of my students were even left of me at a certain point. Finding students who had an alternative viewpoint was actually really challenging.

SF: Yes. Well at Cornell, we’re certainly a fairly liberal place. But there is a pretty strong conservative contingent there. I think I have a different background in a variety of ways from some of the other students. In discussions of affirmative action policy, I would think about my dad working in a factory and how many of the workers had resented the policy because it was misapplied and misunderstood. That helped, rather than to just think about it from a legal perspective. I believe firmly in affirmative action, but it adds something to the conversation to have students from different backgrounds.

MJC: That’s interesting. My dad was a truck mechanic, and so I was a first generation college student as well, and one of the things that I’ve started to write more about is the elision of class in feminist politics and writing, and how and when we talk about class, or don’t. Where it comes up, right? And so, is there something coming from your class background that has affected your politics?

SF: Certainly with any perspective that we bring to a conversation, whether it’s our gender or our ethnicity or our race or our class, it just gives you a window into real-life experiences. And the ability to look at how things really impact that group of people. And I think that’s one of the clearest testimonies to why we have to make sure that everyone’s represented in elected office. Because some people firmly believe that we need to elect women so that women’s issues will be paid attention to. Yes, but that’s a really problematic line of rhetoric, because it has to be every elected official’s responsibility. It’s important to have the different perspectives because things are brought up that wouldn’t be otherwise, and considered in different ways.

MJC: So Sandra, can you talk about three to five people who’ve been very influential in the development of your feminism?

SF: Well, I’ve been thinking about that and it’s a hard question. There were two groups at Cornell who were very influential when I was discovering activism and advocacy, because for me that was really where I fell in love with this kind of work. It was with the advocacy and the activism, feeling like I could create change in people’s everyday lives. There were students who were ahead of me a bit who founded a group called Students Acting for Gender Equality on our campus. And there were professors there who were very instrumental in opening up my exposure to some of these ideas, to advocacy.

MJC: Hmm, okay.

SF: And then also, after college, I went on to Sanctuary for Families in New York City. They provide services to victims of domestic violence and victims of human trafficking. And it’s a very diverse clientele. I know when I was there they were speaking dozens of different languages. You might have somewhat ephemeral ideas about gender inequality as it’s enacted on people’s bodies. But when you talk with victims of domestic violence or sexual assault—and often you get to talk to people of different cultural backgrounds with different ideas about gender and sexuality—you see how it plays out in their lives.

And then my peers in the formal career world, talking to other women my age and my mom’s age, and hearing about how they navigate these questions of work and family and seeing how that’s happening with my LGBT friends. And finding out how it’s different, or the same. And how it’s happening for the millennial generation—these real-world experiences and conversations and movements. And how these movements, the second wave and since then, have really impacted people’s lives.

MJC: Do you think that we can talk about any sort of cohesive feminist movement right now?

SF: I think that there are many feminist movements, and there are certainly many different schools of thought and approaches and maybe actions that we’re working on, and that’s a good thing. That’s got to be a strength. Because too often we’ve been seen as a monolithic movement, and when that happens, you inevitably only appeal to certain communities and you only represent certain communities. Those are, I think, more problematic weaknesses than having us be spread in different directions. It’s important for everybody to try and come together and work on our concerns in a concerted way, but our diversity has to be a strength.

MJC: One of the things I loved about your Arizona List talk was the reproductive justice framework. Obviously, it resonated so much given my own work. And there is a clear difference, obviously, between rights and justice and how they are enacted and who gets involved. So can you say more about reproductive justice and how you came to it, what it means to you as a framework for your work?

Sandra Fluke at the 2013 Arizona List luncheon with Honoree Carolyn Warner (Photo credit: Arizona List)

SF: My coming to it was really primarily through people in Law Students for Reproductive Justice, a national organization with chapters at law schools. For me, this framework is about broadening our perspective. Broadening it to make sure that we remember that reproductive rights on its own or reproductive health on its own includes not just having access to abortion but includes access to all kinds of health care and the ability to have children, not just the ability not to have children, and men’s healthcare as well as women’s healthcare. Then the justice framework, beyond that, is to really make sure that we have in mind accessibility and affordability. One of the main weaknesses in our legal framework now is that, on a variety of issues, not just reproductive, we don’t have that lens, that we may have the right to be able to access something but we can’t find the money for that need. So I think the justice framework brings that clearly into our line of sight. And that’s also a much better framework for looking at intersectionality, and considering how LGBTQ identity or other multiple identities, various communities of color, of different financial circumstances, of employment situation, how those different identities intersect with reproductive rights and health needs. Reproductive justice is really beneficial; it makes it so clear why we should think in terms of intersectionality.

MJC: Have you been thinking at all about how a human rights framework might come into this?

SF: It’s interesting because I was talking about reproductive justice and in one discussion, someone said to me, “But moving away from the rights language is moving away from the human rights framework.” And I think that, again, a strength of this has to be using different frameworks. I don’t think that we all have to be working off the same one. I have really clear reasons why I prefer the reproductive justice framework, but I think it is important that we continue to have a human rights dialogue in this country. It’s a lot about ourselves, and not just about our work internationally. It’s challenging because, pragmatically, to focus on immediate legislative goals and court gains, a human rights framework has challenges in our country, a lot of challenges. But I do firmly believe in it and I think it’s important that we continue to talk about it in that way as well.

MJC: Right. Human rights isn’t a field that I have spent that much time in until recently, as my background is in sociology and health, so I’ve been trying to think through what’s salvageable from human rights, which is gendered in really interesting ways–I mean, the discourse itself–and how to bring that together with the reproductive justice framework.

SF: I did human rights work in law school and it’s really amazing how powerful that framework is in international contexts, and in other countries that have a real respect for it, have a real respect for international treaties. It’s one of the reasons that we have to get CEDAW ratified…because we hear about and sense this in other countries, where women are petitioning, saying we need reproductive justice, it’s a violation of CEDAW, and we’re a member of CEDAW. And then, I think it’s happening in Afghanistan, where a legislator on a panel said, “But how seriously can we take this obligation? Because the U.S. isn’t a party to it.” And we are undermining the hard won accomplishments of our sisters throughout the world.

MJC: Yes, right. So another thing you talked about at the luncheon that really struck me is the second wave/third wave issue, which has come up in more than one setting in the last year. I connect often with second-wave feminists, such as those affiliated with Planned Parenthood Arizona, who wring their hands about generation gaps, asking “Where are all the young people?” Exactly the question that you got at the Arizona List event. Of course, we know the young people are there. I know because I teach the college students, so I see them all the time. But what’s going on with second wave/third wave, and how can we get folks talking to each other and finding commonality?

SF: This has to be something that happens in movements. I don’t think there’s any denying that second wave feminism was a key moment, something pretty incredible, but it’s not going to be able to be sustained in exactly the same way. It’s going to change and go through phases, and so to a certain extent, we need to accept that it’s natural for movements to have different shapes and look differently for different generations, and realize that some of it is about generations not being able to see each other. And I get this question a lot from very devoted ladies of a certain generation, but it’s often asked of me at fundraising events that young people can’t necessarily afford or events that aren’t really the style of young activists. And young activists are really just working endlessly in a different space. So I try to reassure people that millennials are here, and it’s partially a problem of just not connecting.

But what we’ve got to do is try to share leadership. Because millennials often feel like they try to be involved in things, but there is a resistance to change, and I know that there’s genuine concern from this earlier generation about where it’s going. So if we can come together and find ways to work together, that would be to all of our benefit. But again, having different groups trying to reach different audiences is an asset, as well. So even if we have that divided approach, that’s not always a bad thing. But when we talk all the time about where are the young people, that doesn’t bring in people and that doesn’t make them feel welcome. And if anything, it pushes them out, makes them feel invisible. So we do have to think about our language on this one, and make sure we’re sending the right signals. It’s all about making sure we have a forward-moving agenda and we’re not just focused on defending the battlefield, because that’s not going to bring people to our movement, either. That’s not going to be something that young people connect with—not that they should or shouldn’t—it just doesn’t work that way.

MJC: I invited Tracy Weitz to come to Tucson recently, and we had several students attend the CoreAlign event that we put on, and we talked about this very question. We asked the young people in the room, had they gotten involved with various things. One of our graduate students had been part of Planned Parenthood for a long time and we asked how he became involved. He said that he was asked to do the website, which is a very typical thing; we need someone to do it, we go to the young generation, and instead of asking them what their ideas are, what their needs are, we’re going for tech help. I see that over and over again, so that was a real take-home message from that meeting.

SF: [Dog barks] Hold on one sec…

MJC: That’s okay.

SF: My own personal guard dog. [Laughs]

MJC: I think we can legitimately call you a celebrity. You have a Wiki page, you were championed by HuffPo as TIME Magazine Person of the Year, you speak widely, and you have name recognition among feminists and progressives across the United States. How have you handled this newfound celebrity? Surely as an undergrad at Cornell and even a law student at Georgetown, you weren’t quite so “famous”—so how has your life changed?

SF: You know, it certainly makes me more aware of those things, it makes me more aware of the ways in which we talk about people who are in the public eye and exert this ownership over them. We have the right to have all these opinions about how they look and how they dress and how they present themselves in ways that really aren’t all that relevant and aren’t really any of our business.

SF: You know, it certainly makes me more aware of those things, it makes me more aware of the ways in which we talk about people who are in the public eye and exert this ownership over them. We have the right to have all these opinions about how they look and how they dress and how they present themselves in ways that really aren’t all that relevant and aren’t really any of our business.

MJC: Right.

SF: And we talk about them as commodities. And I’ve become more sensitive to that in the process, but also to the ways in which it limits one’s ability to push on the boundaries of injustice. You have to recognize that there are different roles in advocacy movements, and the person who is in the public spotlight has certain advantages in what they can accomplish, but also some limitations in what other roles they can play.

MJC: Do you ever have moments where you think, gosh, I just want to go back to life the way it was?

SF: Yeah.

MJC: [Laughs] Where people aren’t always calling you for an interview?

SF: Of course, there are those kinds of moments. But I feel like, when you have an opportunity to accomplish something positive for the ideals that you believe in, then you have a responsibility to step up. So what I’m usually thinking about and worrying about is, am I making enough of a difference? Is the impact adequate, that what I’m doing with my time is the right thing to be doing? Or should I be trying a different strategy?

MJC: After the luncheon, I went home and said to my family how delighted I was to have heard your talk. I was telling my daughters about your talk, and the thing I was trying to convey to them was just how impressed I was with your ability to make lemonade out of lemons. Like this really shitty thing happened that thrust you into a spotlight. I said, “You know, somebody said something not very nice about her. She was already doing interesting work; this helped her have a bigger platform in some ways. And she’s really risen to the occasion.” Because I think that not everybody does, right? And as somebody who is raising girls, I’m trying to instill in them the lesson that life isn’t always going to be great. And especially if you’re outspoken, people are going to be kind of nasty to you. So how do you react to that? My girls were pretty impressed by the way, and now you have fans among the nine- and eleven-year old crowd.

SF: I’ve heard from a variety of moms and dads about how it gave them an opportunity to talk to daughters and their sons about some of these things and I’m glad for that. We should all feel like we can just be individuals, and we don’t have to be representative of our race or our gender or our orientation or any of that. But I do often think, you can’t walk away from this opportunity or that opportunity because too many women do that. And it means that we don’t get as far, and we have to keep pushing to make a difference to the women who will come after you. So I want to put a bit of pressure on myself in that respect, as well.

MJC: Mm-hm.

SF: In the end I think it’s frequently good for me, because we don’t always push ourselves enough, and then we may lose out on things. The thing I try to impress upon people is that it looks scarier before you are dealing with it. That once it’s something you deal with, you realize you can. And I have folks come to me and say, “You’re very strong, you can keep fighting for this thing,” and I appreciate that in spirit, but I’m not different than other people. We all can withstand these things. We’re allowing other people to limit us when we let the fear hold us back. Everybody has to do it in ways that keep themselves safe. And different people have different emotional circumstances in terms of what they need to do to create emotional safety for themselves. But we really are strong enough to handle it. And I hope that other people realize that, because I continue to put myself out there and they can, too.

Sandra Fluke at the Arizona List luncheon in Tucson with Congressman Ron Barber and attorney Annette Everlove (Photo credit: Arizona List)

MJC: I agree. It’s not easy though, is it?

SF: No, no. But often I remember what Leader [Nancy] Pelosi said to me at one point. She was sharing a religious parable with me and said, if you get to heaven and Saint Peter asks to see your hands and there are no scars, then that must mean you didn’t think there was anything worth fighting for.

MJC: That’s very nice.

SF: So there are things that are worth fighting for, the scars and all of it.

MJC: Yes. And take the opportunities when they come, right?

SF: Yes.

MJC: Talk to us about a day in the life of Sandra Fluke. Presumably, you wake up, ingest some caffeine, and get dressed like everyone else. And then what? Are you practicing law?

SF: I am.

MJC: Are you doing presentations? What does your life look like on a daily basis?

SF: Most days look different from each other. That’s one of the things that I’m getting used to, is the variation and instability of the kind of work that I’m doing. I do legislative advocacy, a good bit in Sacramento at the moment. I’m working on human trafficking bills there, the domestic worker bill of rights, and also an anti-poverty bill. So those are a couple of priorities, and on a national level, I’m focused on immigration reform. I’m also really concerned about the sexual assault crisis in the military, something I’d like to try to do more on. And find some ways to be more of an ally with trans folks and the multiple battles that they’re fighting right now.

MJC: So speaking of allies, let’s talk a little bit about race. And I don’t know if you know this, but your name has come up in relation to the Quvenzhané Wallis issue. It’s been very interesting to see…

SF: I heard a little bit about it, at least.

MJC: We had a piece that one of our collective members published on her blog, and then there was a response that we published at The Feminist Wire, and it was along the lines of, “Where were the white women when The Onion called Quvenzhané Wallis this hideous term, because they all came out for Sandra Fluke?” It was a really interesting moment of thinking about race and celebrity and what “we” respond to. So I’m curious about how you think about your work in relation to racism and anti-racism.

SF: You know, I try to approach it thoughtfully, but with the intent that I would rather be involved and make a mistake than not to be standing up at all. So I try to talk about issues of race and how they intersect and how the work that I’m doing is about that kind of work. You know, the domestic worker bill of rights, the public assistance bill. Working on how race intersects…those are fights that we are still having. And that can be sometimes challenging for a white person to do, but I try to do it thoughtfully and a way that I don’t think that I’m being offensive or exclusive, and recognizing that I can’t be the lead voice. Those are communities that have their own leaders, and what I can be is an ally, and try to amplify the work that they’re doing. I try to be a thoughtful ally, but I also recognize that I’m not always going to get it right. And you know, the situation with Miss Wallis is one of those instances where I’m not sure that I did get it entirely right. I think that I didn’t. And so the approach that I try to take is, okay, I’ll hear the concerns, I will try to integrate them into my work, I will apologize when it’s appropriate to do so, but the promise that we all have to make to each other is that we’re going to work on this together and try to be accepting that we’re trying to work on it together. And sometimes I think that’s challenging. I realize where the frustration comes from, I totally get the anger and frustration about it, but I try to be pragmatic in my work, and I appreciate that from other folks when they are able to say, “Okay, here are my concerns, and, you know, thanks for apologizing and let’s move forward trying to work together.”

MJC: So thinking about reproductive justice, one of the things that Tracy [Weitz] said when she was here that really resonated with me was that we don’t really have visionary leaders. What do you think about that? Do we need a visionary leader? Do we need a Sandra Fluke to really take off and be a spokesperson? I mean, what would that look like?

SF: It’s not me! [MJC laughs] One of the things that I struggle with is, I’ve always been much better as an implementing leader than as a visionary leader. So sometimes when I’m put in that role of, what should we be doing next, I’m all, I don’t know, but when you figure it out, I’ll make it happen. So it is helpful to have certain rallying points, but I’m not sure those need to be people. Those could be ideas, those could be moments, and shared experiences. Perhaps it’s one of the things that feminism and social justice teach us, which is that there is not going to be someone who is adequate as a visionary leader for an entire movement that represents people in different circumstances. I don’t think that searching for that person is where I would put my energy. I am more focused on working together and how we can connect various movements. I think that’s our real challenge: how can we work together across social justice movements and see these as one fight?

MJC: Mm-hm, it’s important. And trying to figure out where to intervene. Here in Arizona we’re very active in border issues, immigration issues. So how to connect those worlds, which are not often connected? And not only are they not connected but the same people don’t necessarily want to work on those issues. Some of the Planned Parenthood folks are probably not LGBTQ supporters, and they’re probably not all in favor of immigration reform. So it’s a really interesting set of issues. All right, moving on. If you could give your thirteen-year-old self advice, what would you say?

SF: To try to relax a little bit and not plan so much! Because I am someone who always wants to have a firm plan and detailed ideas about how I’m going to accomplish this, where I’m going next, those sorts of things. Certainly the last year and a half has shaken up all of those plans.

MJC: So what are the things that keep you going, given all the challenges of the kind of work we do?

SF: To be honest, a sense of what other option would there be? You have to keep going because it’s your responsibility. This is the right thing to do. I was raised with a strong sense of duty and responsibility, so I keep going out of that sense. But I have a very supportive fiancé, I have a puppy, and they support me tremendously, and I find ways of taking care of myself. I also have a great team that I work with.

MJC: Good, good, that’s important. The sense of community is huge. I think sometimes if I didn’t get up and start my day with email, with TFW folks and particularly Tamura and Darnell, I don’t know that I would keep going sometimes. You know, that sense that it’s not just you, right? It makes a huge difference. So, other things that you care to share? What you like to do, fun things? Things you want to keep hidden? [MJC laughs] No comment?

SF: I have some things I would still like to keep private.

MJC: I’m going to write “no comment.” [Both laugh] How about running for office? Have you ever thought about that?

President Obama and Sandra Fluke

SF: Oh, yeah, of course, you know, I get asked that question a lot, so I have to think about it. The place I’ve come to is, I am really concerned about what our lack of representation looks like. A democracy is one that looks like the people, and ours doesn’t right now. So that’s women, that’s LGBT folks, that’s people of color, immigrant families, all of that. And so I am concerned about that, and I think that we have to think about that at an individual level. I speak frequently to audiences of young people of these communities asking them to think about it personally. Would you do this? Could you do this? And trying to get people past those barriers that they have, saying, “No, not me, I can’t.” And all of the reasons that they’re giving. So I try not to be hypocritical, but if the right opportunity presents itself at some point, I would consider it.

For me it’s thinking about, what is the best way to accomplish the work that I’m doing? And in some ways that might be a good opportunity, in other ways it might limit the work, so I think a lot about that aspect of it. But running for office wasn’t something that occurred to me before this experience and people started asking me all the time. I’m someone that has a policy degree and a law degree, I’d worked in social services for many years, done a lot of organizing and activism, and cared a lot about these types of issues, and I thought at the time that running for office was not possible for me to do. Politics was only something that this elite group of people did, their families had been in politics for a long time, they had that possibility. That’s really problematic, that people are thinking that way, with a set of qualifications such as mine that sounded exactly like the people who’d be considering running for office.

When we’re not thinking that’s possible, that’s a significant problem. And there are a lot of people with really significant barriers to get to that point, and we have to address that, as well.

MJC: That’s interesting. I always think about it as the difference between democracy with a big “D” and a little “d.” And so we have the big “D” democracy, but do we really have democracy as a process? And really instilling in kids that they could in fact do certain things in their lives, that they had no imagination for, that would be amazing. You’ve probably seen lots of folks whose eyes light up when you talk to them about this.

SF: I think it depends on the community. Because for a certain set of our young people who are relatively better off educationally and economically, I think they are taught that as children, that they can be anything, but then they lose it. They lose it as a teenager and in college, in that process where you don’t see the practical steps for how you would do that. And so it’s reaching down and mentoring in some very practical ways, saying, “Here’s what you should do,” those practical things in showing how is it that this is really done. I sometimes get people who come up to me and say, “I do want to run for office. How do I do that?” You know, how do I get started? I realized that it will take me a decade to get ready or whatever, how do I do that? But then there are other communities, definitely, that far too early have significant limitations placed on what is possible or is seen as possible.

0 comments