On Beyoncé, Benedict, and the Volition of Women

By Lisa O’Neill

At a school mass at my all girls’ Catholic High School, the priest said a homily about chastity, and in particular, sex before marriage. “Let’s say you are about to get married and you are going give your husband a gift, the gift of yourself and your sexuality,” he said. I was listening. I always liked metaphors. “And so you give him this box and he unwraps it and opens it, and in it, wrapped in tissue paper, is a tie. The tie is shiny and colorful. And he looks so pleased and you are both elated.” He continued, “But let’s say, you hand him a box and it’s not wrapped and the box is torn. He opens the box and pulls out a tie. It’s been used. There are stains all over it. How, then, do you think he would feel?” At the time, I had internalized so much Catholic dogma and guilt. I didn’t know to feel outraged. I understood that I was being given a warning, and even though I hadn’t had sex and even though, at that time, I thought I would wait until marriage, I felt deeply ashamed.

After telling this story recently to a friend, she said, “And I bet that he didn’t give the same homily at the all boys’ school, talking about a strand of pearls that was dirty and missing a few beads.” I agreed. I’m sure he didn’t.

The fact that misogyny exists in our culture is something that people usually get. But how much and how often misogyny permeates our everyday life, interactions, and the public sphere is not always considered.

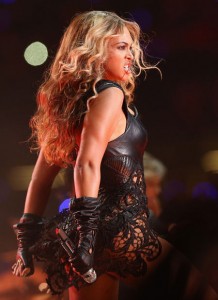

As a lecturer I try to bring in content that students will enjoy, so rhetorically analyzing pop icons and their products seemed to be a win-win situation. When I brought in Lady Gaga, Beyoncé, and Nicki Minaj to my composition courses a year ago to deconstruct their personas, I was excited, but many of my male students were dismissive, not only of these artists as worthy for class discussion but of their legitimacy as artists at all. Some asked why we weren’t looking at male artists. Some of these young men even became confrontational, not only about the content but toward me. When I brought in Beyoncé’s recent Superbowl Halftime Show to examine in light of the controversy it invoked among many conservatives (many asked, “Why did she have to be so sexy?” And, “what about the children?”), one class was largely divided between male students, who called her show inadequate, and female students, who deemed it amazing. By and large, the female students found it empowering. While many students said they didn’t find her performance offensive at all, those arguing that Beyoncé should have worn more clothing, should have danced less provocatively, and should have sung more, were all male.

As a lecturer I try to bring in content that students will enjoy, so rhetorically analyzing pop icons and their products seemed to be a win-win situation. When I brought in Lady Gaga, Beyoncé, and Nicki Minaj to my composition courses a year ago to deconstruct their personas, I was excited, but many of my male students were dismissive, not only of these artists as worthy for class discussion but of their legitimacy as artists at all. Some asked why we weren’t looking at male artists. Some of these young men even became confrontational, not only about the content but toward me. When I brought in Beyoncé’s recent Superbowl Halftime Show to examine in light of the controversy it invoked among many conservatives (many asked, “Why did she have to be so sexy?” And, “what about the children?”), one class was largely divided between male students, who called her show inadequate, and female students, who deemed it amazing. By and large, the female students found it empowering. While many students said they didn’t find her performance offensive at all, those arguing that Beyoncé should have worn more clothing, should have danced less provocatively, and should have sung more, were all male.

I, like many Americans, was as interested in the halftime show as the game itself. Plus, full disclosure, I love Beyoncé. I definitely have had some bones to pick with her over the years, particularly at moments when she has not given full credit to the artists whose work she has used in her performances. But she brings authority to her work and empowers women in her confidence and pursuit of excellence. I appreciate this.

The negative criticism caught me off guard because what I saw was Beyoncé being Beyoncé, and Beyoncé rocking being Beyoncé at that. What I saw as I watched was a woman entirely in her element owning the stage. Beyoncé is a phenomenal entertainer and she—complete with complicated choreography, powerful vocals, pyrotechnic shows, and a backing band of all female musicians—put on an amazing show.

The negative criticism caught me off guard because what I saw was Beyoncé being Beyoncé, and Beyoncé rocking being Beyoncé at that. What I saw as I watched was a woman entirely in her element owning the stage. Beyoncé is a phenomenal entertainer and she—complete with complicated choreography, powerful vocals, pyrotechnic shows, and a backing band of all female musicians—put on an amazing show.

There have already been some amazing critical essays examining underlying sexism and racism in the backlash from her performance. These essays examine the negative responses that might have unconscious motivations and suggest that there are many underlying questions that need to be asked.

One of the essayists asks this question: “Why are we more comfortable with displays of masculinity and sexuality than we are with displays of femininity and sexuality?” She talks about the erotic nature of football itself. And I totally agree: if we didn’t call football “football,” what would we call it? Men in spandex crouching down, running after each other, jumping on top of each other, pinning each other to the floor? There is clearly nothing sexual about this. No, not at all.

I would ask: Why do we still continue to critique female sexuality even when it is expressed in a form that we as a culture promote, condone, and encourage?

The only but essential difference in the expression of female sexuality between Beyoncé’s performance and Superbowl commercials featuring an attractive woman (like this one, or this one, or this one) is the volition of the woman involved. The difference between deeming a woman’s exertion of her sexual power as acceptable or unacceptable seems to depend entirely upon whether or not an “other” is in control of the script. Unlike the commercials where the sexy woman exists as pure eye candy and innuendo, or contributes to the punchline of a joke, Beyoncé is constructing the narrative and that narrative is about her own power.

The day after the Superbowl, Buzzfeed posted a piece called “The 33 Fiercest Moments from Beyoncé’s Halftime Show.” This post was clearly meant to demonstrate the show as a moment of glory for her. Some photos show Beyoncé’s face stilled at a moment of fierce expression. In others, you can see the muscle definition in her arms and legs. Beyoncé’s publicist contacted the website, calling certain photos unflattering, and asked the website to take them down. In response, Buzzfeed wrote a new post with the publicist’s email included and asked: “In what world are these shots unflattering?” In ours. What followed in response to all the attention to these particular photos was the exact reaction that I’m sure the publicist was trying to avoid. Memes shot up that renamed and altered the images: Heavyweight Champion Beyoncé, Performance-Drug Enhanced Beyoncé, The Incredible Hulk Beyoncé. We could dismiss these memes and say: it happens, celebrities take unflattering photos and people make fun of them. And this is true. However, what these memes attempt to do is make Beyoncé appear grotesque, to undermine her femininity and beauty. They take what was a moment from a strong performance and distill it, and thus use it as an opportunity to mock her and strip her of power.

The day after the Superbowl, Buzzfeed posted a piece called “The 33 Fiercest Moments from Beyoncé’s Halftime Show.” This post was clearly meant to demonstrate the show as a moment of glory for her. Some photos show Beyoncé’s face stilled at a moment of fierce expression. In others, you can see the muscle definition in her arms and legs. Beyoncé’s publicist contacted the website, calling certain photos unflattering, and asked the website to take them down. In response, Buzzfeed wrote a new post with the publicist’s email included and asked: “In what world are these shots unflattering?” In ours. What followed in response to all the attention to these particular photos was the exact reaction that I’m sure the publicist was trying to avoid. Memes shot up that renamed and altered the images: Heavyweight Champion Beyoncé, Performance-Drug Enhanced Beyoncé, The Incredible Hulk Beyoncé. We could dismiss these memes and say: it happens, celebrities take unflattering photos and people make fun of them. And this is true. However, what these memes attempt to do is make Beyoncé appear grotesque, to undermine her femininity and beauty. They take what was a moment from a strong performance and distill it, and thus use it as an opportunity to mock her and strip her of power.

Why is it so threatening when a woman owns her own power?

In Reviving Ophelia writer and psychotherapist Mary Pipher writes about the conflicting messages sent to young girls. As children, girls are given many of the same messages as boys, the ones that say that they can be anything they want to be, the ones that say they should express their views, the ones that encourage them to work hard and to follow their passions. But once they reach adolescence, they are given a new slew of messages that say they shouldn’t be too opinionated if they want to attract a boyfriend and they should want some things (a husband, a house, a family) more than they want other things (to follow their passions, to pursue their careers). This conflicted messaging plays out in relationship to sex and sexuality in what I’ll call the slut/prude dilemma.

Girls are told they need to save themselves for marriage, for the right one, until they are ready. But then when they do so, they are deemed prudes. Girls are told they need to be Daddy’s Little Girl, which means that should deny their own adolescence–their maturing bodies and minds. In a recent episode of the television drama Parenthood, after a teenaged girl gets pregnant and has an abortion, she talks about not wanting to tell her parents because “they would see me differently.” Not as their perfect chaste daughter, but as the sexual person she has grown into, and with all of the responsibility that comes with that.

Girls are told they need to use their looks, their bodies to attract men. But when they attract men and follow their desires as sexual beings, they are called sluts. The fact that people use the term “male slut” reveals how women are made to bear their sexuality as a burden when men typically are not.

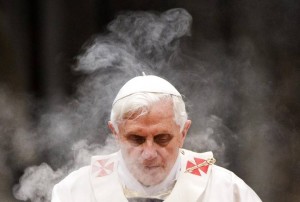

Pope Benedict XVI resigned his post as pope last week. Although I am no longer a Catholic, I still feel connected to the Church by nature of how long and how much the rituals and rhetoric were part of my life. When I heard the news I was excited because what I’ve seen since is his continual work to push the Church backwards, to work against the evolution of our culture and cultural understanding, particularly in relationship to women and the LGBTQ community.

Pope Benedict XVI resigned his post as pope last week. Although I am no longer a Catholic, I still feel connected to the Church by nature of how long and how much the rituals and rhetoric were part of my life. When I heard the news I was excited because what I’ve seen since is his continual work to push the Church backwards, to work against the evolution of our culture and cultural understanding, particularly in relationship to women and the LGBTQ community.

In addition to saying that along with abortion and euthanasia, gay marriage is a threat to world peace, Benedict reaffirmed the Catholic Church’s opposition to women priests, saying “Is disobedience a path of renewal for the Church?” Many Catholics who are for the ordination of women, point to iconography that shows women performing sacraments in the early church. Or they will explain that Jesus, in choosing only men as his apostles, was acting according to the customs of his time, and that we should act according to the customs of ours. A 2010 poll by The New York Times and CBS reported that 59 percent of American Catholics favor the ordination of women. Pope Benedict authorized excommunication for women who had been ordained, in opposition to the Vatican’s position, as priests in the Catholic Church.

But perhaps the most disturbing issue in relation to Pope Benedict XVI and women was when he appointed an American bishop to “rein in” the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, a group that includes 80 percent of American nuns. What did they need to be reined in from? Focusing too much attention on the poor and issues of social justice. Not speaking up enough about abortion and euthanasia. The Vatican also accused the nuns of being too feminist, saying The Leadership Conference of Women Religious supported “radical feminist themes incompatible with the Catholic faith.” Member of the LCWR Sister Beth Rindler told The Daily Beast, “We believe that God created men and women equally. That’s where we [and the Vatican] clash.”

But perhaps the most disturbing issue in relation to Pope Benedict XVI and women was when he appointed an American bishop to “rein in” the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, a group that includes 80 percent of American nuns. What did they need to be reined in from? Focusing too much attention on the poor and issues of social justice. Not speaking up enough about abortion and euthanasia. The Vatican also accused the nuns of being too feminist, saying The Leadership Conference of Women Religious supported “radical feminist themes incompatible with the Catholic faith.” Member of the LCWR Sister Beth Rindler told The Daily Beast, “We believe that God created men and women equally. That’s where we [and the Vatican] clash.”

Growing up, the Catholic Church told me I was made in God’s image but wasn’t fit to serve in the vocation of priest. They told me my body was not to be used to express my sexuality until marriage, and then, my body should be used for the benefit and pleasure of someone else. Society was telling me to be innocent but also desirable. My body was not acceptable as it was—thighs too thick, hips and feet too big, and breasts too small—so I must make myself into a package that fit the standards so that I would be desirable.

Whether manifesting as the media’s critique of the movements of a female artist or as decisions that limit the role of women in religious life, the appropriate use of a woman’s power is largely defined by the rules of our patriarchal culture.

Last fall, I started going to West African dance classes. At first, I hesitated. Wouldn’t this be cultural appropriation for me, a white woman, to do these moves and gestures, especially in a room full of mostly other white women? At first, I felt discomfort when the instructor used the term “our ancestors” because I didn’t want to try to claim a right to a culture that doesn’t belong to me. But when I stayed and when I danced alongside these other women at the instruction of our energetic, soulful teacher, I saw that this dance and this practice was about homage and tribute, not about taking something with no sense of where it came from. The instructor, who studied dance in Guinea, connected the dance to its roots. She talked about dance as an offering. She asked us to let go of self-consciousness in order to pay tribute to our ancestors and to all those in the room with us.

The moves required us to squat, pop our hips, and shake our asses. And as we do so, we move down the floor so that, eventually, we are dancing eye-to-eye with the drummers. At first, I found myself shy and awkward. The only context in which I had seen this kind of movement deemed appropriate was on dim dance floors where I would move self-consciously not wanting to garner too much attention. And yet, these are not the same moves, because they are coming from a much deeper place. And this dance is not about seeking approval or permission. In the dance, we are harnessing our sexual energy but it is not about sex and it is not about sexiness. It is about honoring our bodies and what they can do. It is about dancing in solidarity with our community. The dance is about our power as women, and it is not for anyone else. The dance is for us.

________________________________________________

Lisa M. O’Neill lives in Tucson, where she writes and teaches writing. She has developed curricula for and taught writing workshops with incarcerated students at Tucson detention centers and presently serves on the board of Casa Libre en la Solana, a literary nonprofit supporting Tucson writers. Her work has most recently been published in defunct, The Fiddleback, drunken boat, and Diagram. She is the creator and editor of The Dictionary Project, a literary project rooted in bibiomancy and the dictionary.

Lisa M. O’Neill lives in Tucson, where she writes and teaches writing. She has developed curricula for and taught writing workshops with incarcerated students at Tucson detention centers and presently serves on the board of Casa Libre en la Solana, a literary nonprofit supporting Tucson writers. Her work has most recently been published in defunct, The Fiddleback, drunken boat, and Diagram. She is the creator and editor of The Dictionary Project, a literary project rooted in bibiomancy and the dictionary.

8 Comments