In Mourning

By Isaiah M. Wooden

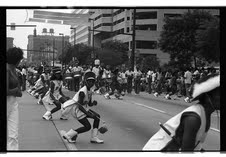

I used to love marching bands. Not the kind that show up on television screens across America on Thanksgiving mornings every year, but the ones that would unexpectedly assemble on the streets of my east Baltimore neighborhood on random spring nights with a robust drum line, a core of flag-bearers, and an energetic group of twirlers and shakers: the ones that would bang out the latest house beats and have all of the kids on the block, and some of the adults too, dancing.

For those of us too young to go to the club and too broke to pay the five dollars to get into those house, err, rent parties, the sight of a marching band provoked tremendous excitement. Marching bands promised ecstatic moments of poppin’, lockin’, swaying, sweating, cheering, and, inevitably, dance battling. For me, it meant that I could test just how well I had copied my brother’s dance moves. And since everybody around me would be committed to executing their steps fully, it also meant that I could go HARD!

More than that, the presence of the band promised additional evidence of the tremendous love that flowed through our community. It wasn’t uncommon to see multiple generations of a family laughing and boogieing together alongside of next-door neighbors, childhood friends, and schoolmates. Indeed, I often hoped that I would run into an aunt, uncle or older cousin. I’d beg them for a dollar so that I could go to the corner store to buy a fruit punch soda, some Sour Patch Kids and a Mr. Goodbar. If I chose my purchases wisely, I might even have extra change to buy a bag of Utz the next day.

I loved marching bands because they signified freedom.

The rhythm of the drums had this really powerful way of pressing pause on any discord in the neighborhood. When the band played, I could confidently travel down those blocks that I might typically avoid for fear of landing in a scuffle. Everyone would see that I was following the band and would leave me be. I was following the band. Indeed, I followed marching bands across the city into neighborhoods I didn’t even know existed.

I can recall traveling with a teenage friend—I was seven—to watch the parade that used to kick off what was once called the “Soul Festival” and, later, the “AFRAM Expo” in Baltimore. While I can’t quite remember how we got to there—likely a city bus—I do know that I was wildly excited about seeing some of the legendary marching bands—New Edition, The Westsiders—that, up until that point, only existed in my imagination. I was so enraptured by the spectacular displays of originality and creativity that I ended up losing my friend somewhere along the parade route. I spent most of the afternoon trying to convince one of the women working in the designated “children’s area” that if she gave me the necessary dollar and change to catch the bus, I’d be able to find my way home. She kept looking at my seven-year-old-self unconvinced. I kept working at it, and, eventually, she relented. After taking the bus northward and sprinting eastward, I finally arrived home full of gratitude: not only for the kind lady’s generosity and for my safe return, but also for the taste of freedom that loving marching bands had once again afforded me.

I loved marching bands.

I loved marching bands—that is, until one fateful Saturday afternoon during my sixth grade year in middle school. When I heard the beat of the drum that sunny spring day, I went chasing after it like I had done so many times before. I ran into a few friends along the way. We danced. We followed the beat of the drum. We traveled deep into the recesses of East Baltimore. When the drums stopped, however, I was shocked to discover just how far away from home we had ventured. And soon, I was reminded of the dangers of being in a neighborhood that was not my own, especially after the drums had gone silent.

I loved marching bands—that is, until one fateful Saturday afternoon during my sixth grade year in middle school. When I heard the beat of the drum that sunny spring day, I went chasing after it like I had done so many times before. I ran into a few friends along the way. We danced. We followed the beat of the drum. We traveled deep into the recesses of East Baltimore. When the drums stopped, however, I was shocked to discover just how far away from home we had ventured. And soon, I was reminded of the dangers of being in a neighborhood that was not my own, especially after the drums had gone silent.

As I exited one street and turned onto another, I discovered that a small crew of teenage boys were following me on bikes. I didn’t think too much of it until they, seemingly all at once, hopped off of their two-wheelers and began to ram them into the back of my legs. A sharp blow to the face came soon thereafter. I feared additional blows might follow so I scrambled for a plan.

Recognizing that I was outnumbered—but also not one to shy away from a fight—I decided to throw one quick punch at the person who had assaulted me, connecting it with his jaw, and then to run as if my life depended on it. It did. There are many championship-winning sprinters and cross-country runners in my family. As I raced through the streets, I attempted to channel every ounce of their speed, will, and endurance. I prayed that it would carry me back to my own stoop. It did. I didn’t stop running until I reached the edge of my block. I had long since left the group of boys who thought it would be fun to attack me from behind. It didn’t feel safe to stop running, however, until I was back in familiar territory.

After spending several minutes collecting my breath, I walked down the block, up the front steps to my house, into the kitchen and poured a glass of water as if nothing happened. I wasn’t going to tell anyone that I had been jumped. My father somehow already knew. A bruise on the left side of my face, it seems, started telling him the story before I had a chance to utter a word. My brother also knew. When he asked me directly about the bruise, I admitted to the violence that had just taken place. And as the words crossed my lips, I broke. He laughed. Getting jumped was a sort of rite of passage, he said. Something certainly transitioned that day.

My love for marching bands perished.

I could no longer trust the beat of the drum or the motion of the crowd to protect me from the violence that lurked in the silences. It hadn’t. It wouldn’t. I felt violated and betrayed. I mourned a love lost.

I’m still mourning.

____________________________________________________

Isaiah M. Wooden is a writer, performance-maker, and doctoral candidate in Theater and Performance Studies at Stanford University. He was born and raised in the great city of Baltimore, MD.

Isaiah M. Wooden is a writer, performance-maker, and doctoral candidate in Theater and Performance Studies at Stanford University. He was born and raised in the great city of Baltimore, MD.

12 Comments