A Black Feminist Comment on The Sisterhood, The Black Church, Ratchetness and Geist

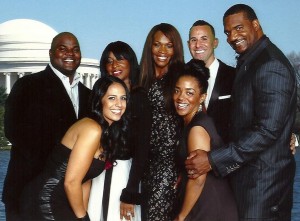

There’s been much talk about TLC’s new show The Sisterhood, a reality show about the lives and struggles of Ivy Couch, Domonique Scott, Christina Murray, DeLana Rutherford, and Tara Lewis, five pastor’s wives in the Atlanta area. While some critics are threatening to boycott the show, and others are framing it as evidence of black [male] preachers losing their way (which I guess is synonymous with the Black Church losing its way, but that’s another issue), millions of others, myself included, a former “first lady” and black feminist scholar of religion, race and media, are flocking faithfully to the television screen on Tuesday nights with popcorn and bottled water in hand.

There’s been much talk about TLC’s new show The Sisterhood, a reality show about the lives and struggles of Ivy Couch, Domonique Scott, Christina Murray, DeLana Rutherford, and Tara Lewis, five pastor’s wives in the Atlanta area. While some critics are threatening to boycott the show, and others are framing it as evidence of black [male] preachers losing their way (which I guess is synonymous with the Black Church losing its way, but that’s another issue), millions of others, myself included, a former “first lady” and black feminist scholar of religion, race and media, are flocking faithfully to the television screen on Tuesday nights with popcorn and bottled water in hand.

And let me be clear: like many, I’m “sick and tired of being sick and tired” of the operative mediation of the global racist and sexist imagination through black women’s corporeal realities. I’m tired of mass mediated notions of “black womanhood” being both the adjective and the noun that modifies and constricts space, time and meanings. I’m tired of black women consistently serving as—through both overdetermination and consent—televisual artifacts for establishing white, black and other “normalcy.” And yes, I’m sick and tired of black women functioning as cultural mediums for soothing primal fears, representational tropes for suckling the collective fascination with black female sexuality, and work horses for demonstrating a mastery of unscrupulousness and otherness. I’m tired.

And yet, I’m also admittedly drawn in to this show and others like it, week after week. Like so many others before them, Ivy, Domonique, Christina, DeLana, Tara and many other reality TV women, inspire all kinds of repulsions, attractions and anxieties. However, they also satiate [some of] our ratchet taste buds. Can we have a moment of honesty? The Sisterhood is a hit show. And this isn’t because no one’s watching it.

And yet, I’m also admittedly drawn in to this show and others like it, week after week. Like so many others before them, Ivy, Domonique, Christina, DeLana, Tara and many other reality TV women, inspire all kinds of repulsions, attractions and anxieties. However, they also satiate [some of] our ratchet taste buds. Can we have a moment of honesty? The Sisterhood is a hit show. And this isn’t because no one’s watching it.

So what’s the draw? The Sisterhood creates a conflict between public politics, private realities and personal taste. However, this war between the emperors’ coat of high culture and the everydayness of his nakedness is nothing new. This ongoing juxtaposition highlights the ever increasing tensions between the “cultured” and the “ratchet;” the former drawing attention to so-called taste, tact, refinement, civilization and genius, and the latter calling attention to the so-called vulgar. While the former is purported to arise out of the Geist – the intellectual inclinations – of our times, the latter is purported to spring forth from the worst of black culture. However, what better communicates the spirit of the time than the ratchet? And no, I don’t mean the ways that ratchet gets deployed to project a collage of derogatory meanings onto black women’s bodies. I’m referring to the ways that ratchetness often undergirds the ricocheting of raw emotions and missiles of unfiltered truths.

To uncritically bash The Sisterhood is to toe the expected party line. To demonize the show is not only an attempt to maintain a position of moral superiority, but an assay to construct and limit meaning for the audience—an audience that may in fact connect with the human qualities of the ratchetness therein. And trust me, I get the critiques regarding black female representations in media. This needs to be called out everyday all day—but not while asphyxiating black women’s complex identities with mythological notions of black women’s heroic genius. In short, binary oppositions don’t work. They set up “us” versus “them” politics, which are both totalizing and reductive. I think a better suggestion might be to think about the heroic qualities of black women’s genius, that is if you buy this argument, as at times being a bit ratchet. Identities and tastes shift in shades of grey, not monochrome. That said, we don’t need another schemata. And we damn sure don’t need another exceptionalist social fiction to cancel out our complex subjectivities, which can neither be packaged nor wholesaled, by the way.

To uncritically bash The Sisterhood is to toe the expected party line. To demonize the show is not only an attempt to maintain a position of moral superiority, but an assay to construct and limit meaning for the audience—an audience that may in fact connect with the human qualities of the ratchetness therein. And trust me, I get the critiques regarding black female representations in media. This needs to be called out everyday all day—but not while asphyxiating black women’s complex identities with mythological notions of black women’s heroic genius. In short, binary oppositions don’t work. They set up “us” versus “them” politics, which are both totalizing and reductive. I think a better suggestion might be to think about the heroic qualities of black women’s genius, that is if you buy this argument, as at times being a bit ratchet. Identities and tastes shift in shades of grey, not monochrome. That said, we don’t need another schemata. And we damn sure don’t need another exceptionalist social fiction to cancel out our complex subjectivities, which can neither be packaged nor wholesaled, by the way.

The Sisterhood isn’t “hurting the church image…[or] giving God a bad name.” Religious people have already done that. Neither is it “abominable and offensive to the Christian/African American communities.” I can think of a few other things, all ending with “isms” or “phobia,” to fit that bill. And finally, it’s not evidence of black [male] preachers or the historical Black Church losing its way–I haven’t even mentioned how the eve/gender politics here are troubling at best. And to be sure, I’m not saying whether the Black Church or the black [male] preacher has lost their way or not. That’s an entirely different conversation. For starters, I think I’d first need to know what the “way” once was or imagined to be. And truly, The Sisterhood isn’t even a representation of the Black Church. As far as I can see, there are only two wives from historical black churches (hold this thought) on the series–whose church would likely define themselves in such a way, Ivy and Domonique.

The Sisterhood isn’t “hurting the church image…[or] giving God a bad name.” Religious people have already done that. Neither is it “abominable and offensive to the Christian/African American communities.” I can think of a few other things, all ending with “isms” or “phobia,” to fit that bill. And finally, it’s not evidence of black [male] preachers or the historical Black Church losing its way–I haven’t even mentioned how the eve/gender politics here are troubling at best. And to be sure, I’m not saying whether the Black Church or the black [male] preacher has lost their way or not. That’s an entirely different conversation. For starters, I think I’d first need to know what the “way” once was or imagined to be. And truly, The Sisterhood isn’t even a representation of the Black Church. As far as I can see, there are only two wives from historical black churches (hold this thought) on the series–whose church would likely define themselves in such a way, Ivy and Domonique.

The Sisterhood is evidence of our obsession with brown women’s lives and our pornotropic desire to lift their curtains and see everything. In addition, it’s evidence of the fluidity between religion and culture, and the myriad ways that each cross-pollinates the other, thus broadening, limiting and confusing all kinds of meanings. An example of this is the construction of the “first lady” concept for the show, a Black Church conception structured in both politics of respectability and patriarchal dominance, aimed at constructing alternative identities–distinct from the hypersexual/sexual savage trope–for black women, particularly during the early twentieth century. As with the FLOTUS, it’s a title of respect for wives in religious contexts that are often theo-socially hostile to women in general. With regard to black women, there’s a long history here apropos race, gender, sex, sexuality, respectability and wifehood. However, I’ll save the politics of race, ladyhood and wifedom for another day.

(Side note: Given this background, I’d be interested to see how the “first lady” title operates for Christina, a Dominican woman married to a black new wave evangelical pastor, and DeLana, a white southern woman who, akin to her co-pastor husband, seems to fancy all things “plantation” (27:56 mark) and soft Christian rock. I’d be even more interested in seeing how this works for Tara, a black body builder married to a Jewish Christian former pastor, both of whom appear to be working with a different set of gender politics. But this, again, is another story.)

(Side note: Given this background, I’d be interested to see how the “first lady” title operates for Christina, a Dominican woman married to a black new wave evangelical pastor, and DeLana, a white southern woman who, akin to her co-pastor husband, seems to fancy all things “plantation” (27:56 mark) and soft Christian rock. I’d be even more interested in seeing how this works for Tara, a black body builder married to a Jewish Christian former pastor, both of whom appear to be working with a different set of gender politics. But this, again, is another story.)

Ultimately, The Sisterhood is evidence of not only our obsession with brown women’s lives, the constant interpolation of religion in culture and vice versa and the static nature of meanings in our society, but our very own and ever expanding frailties, contradictions and complexities as human beings. These women represent the thorny nature of our inner selves, particularly when situated in hostile, novel, and/or uncomfortable environments. Sure. Ivy, Domonique, Christina, DeLana, and Tara aren’t really sisterly (or are they?) and they argue like the women in the Basketball Wives and Real Housewives franchise. But wouldn’t you if pimping your story on reality television somehow became a necessity, or if you found yourself in the midst of a group of others who were geographically, theologically, racially, economically, politically, contextually, and socially different than you? Would you not have differences of opinions and take up, forcefully at that, different positonalities? Seriously. Are we above drama and contradictions? Have we never been pushed to the edge to the point where we want to or choose to take it there? Are our lives without mistakes, conflict, struggles, pain, stresses and moments of dehumanization? Show me a person devoid of these realities and I’ll show you a straight up liar. Yes. That simple.

Ultimately, The Sisterhood is evidence of not only our obsession with brown women’s lives, the constant interpolation of religion in culture and vice versa and the static nature of meanings in our society, but our very own and ever expanding frailties, contradictions and complexities as human beings. These women represent the thorny nature of our inner selves, particularly when situated in hostile, novel, and/or uncomfortable environments. Sure. Ivy, Domonique, Christina, DeLana, and Tara aren’t really sisterly (or are they?) and they argue like the women in the Basketball Wives and Real Housewives franchise. But wouldn’t you if pimping your story on reality television somehow became a necessity, or if you found yourself in the midst of a group of others who were geographically, theologically, racially, economically, politically, contextually, and socially different than you? Would you not have differences of opinions and take up, forcefully at that, different positonalities? Seriously. Are we above drama and contradictions? Have we never been pushed to the edge to the point where we want to or choose to take it there? Are our lives without mistakes, conflict, struggles, pain, stresses and moments of dehumanization? Show me a person devoid of these realities and I’ll show you a straight up liar. Yes. That simple.

The bottom line for me is this: these women are human. They are women with problems from autonomous churches that differ, at minimum, theologically. And like it or not, for Christians and others, theology shapes how people understand themselves in the world. Yes, it shapes both Tara’s unyielding “prayerbush” (s/o to Birgitta Johnson) at the 37:18 mark of the 4th episode and Domonique’s ongoing quest to live out and within her own truth.

The bottom line for me is this: these women are human. They are women with problems from autonomous churches that differ, at minimum, theologically. And like it or not, for Christians and others, theology shapes how people understand themselves in the world. Yes, it shapes both Tara’s unyielding “prayerbush” (s/o to Birgitta Johnson) at the 37:18 mark of the 4th episode and Domonique’s ongoing quest to live out and within her own truth.

Consciously or not, theology re-appropriates politics and ways of seeing by constructing a veil that recolours reality with simultaneous taken for granted notions of truth, hope, transcendence, capitalism, injustice and intolerance. Moreover, the “first lady” position often serves as a protective shield against disagreement. That is, Ivy, Domonique, Christina, DeLana, and Tara are likely used to participating in discourses where their politics and ways of seeing go unchallenged, especially within their congregations.

But what happens when removed from that context? Basically, shit goes awry—just as it would with any other group of strangers with different theo-political-socio-cultural-historical backgrounds and value systems. My favorite on the show is Domonique. Not simply because she keeps it all the way real and clearly isn’t afraid to get it poppin with her co-stars, but because her struggle between the politics of respectability, the structures of dominance that frame her sexual past, and her quest for financial independence and selfhood are real.

But what happens when removed from that context? Basically, shit goes awry—just as it would with any other group of strangers with different theo-political-socio-cultural-historical backgrounds and value systems. My favorite on the show is Domonique. Not simply because she keeps it all the way real and clearly isn’t afraid to get it poppin with her co-stars, but because her struggle between the politics of respectability, the structures of dominance that frame her sexual past, and her quest for financial independence and selfhood are real.

Wherever we land in terms of this show being good or bad or something in between, it’s pretty significant to see a reality TV show centered on people of faith who are flawed with real issues. Perhaps we might interpret The Sisterhood not as an “abomination,” but as an imperfect, yet useful intervention–for the Black Church, black popular culture and black folk living in various communities. These ladies disrupt the monolithic image of the puritanical (and irrational) religious person on one hand, and the exemplary religious heroic genius on the other. These tropes are death-dealing. No one can live them…or live up to them. Let’s face it, we are messy inter-subjective beings with troubles, longings, complications, and inconsistencies–just like Ivy, Domonique, Christina, DeLana, and Tara.

And this is why we watch—and yes, with popcorn and bottled water in tow. Because, unlike the black [male] mega church prosperity gospel preacher constantly being shoved down our throats (pun intended) as the symbol of black churches U.S.A, these folks—these women, are trying to make it and make sense of their messy lives—just like us. And hey, like so many others in academe, the Black Church and without, they want to do it on TV. That said, perhaps we’ve all lost our way.

20 Comments