The System is What's Crazy

Shortly after starting my graduate program at Arizona State University, it became clear I would need to go back on medication for anxiety. Diagnosed for the first time at the age of seven, the destructive behavioral patterns of my adolescence had seeped back into my everyday adult life. Insomnia, panic attacks, impatience, fuzzy and unfocussed thinking – all were taking attention away from I wanted most: extended education and a chance to write.

Because I had been medicated at such a young age, I struggle with a lingering feeling of powerlessness in what my body will ingest. The expectation of patients is that we will maintain a level of compliance with professional recommendations, but many adult patients have the ability to determine when doctors’ orders simply will not work –because the solutions require too much money, the side-effects of a particular medication are too burdensome, and so on.

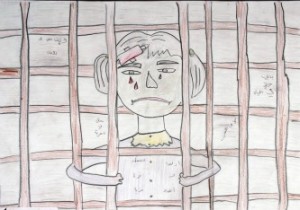

Child patients are in a very different predicament. They embody the social roles of “children” and “patient,” which means they cannot make medical decisions for themselves. From a legal perspective, it would be too risky to have a seven year-old child calling the shots. From a developmental standpoint, there were many components my young brain could not communicate or conceptualize at the time, especially in moments of chronic panic.

From the perspective of long-term health and wellness, however, circumstances facing the child patient are potentially life-changing. At the time I was diagnosed and doctors started experimenting with different medications to control my anxiety, I did not understand what they were doing or why. Too often as an adult I have searched my brain for conversations that never took place, concepts that were never explained, decisions that were never mutual – anything that would allow me to move past this feeling that my brain and body were marked for medical experiment rather than human growth and empowerment.

Adults could see my behaviors improving, and clinicians certainly saw progress in my school attendance and focusing abilities. I seemed less withdrawn during my sessions, one doctor relayed. But I never felt or understood the progress. The goals set by my clinical team to demonstrate “improvement” – less perfectionistic tendencies, being more patient, ability to sleep through the night – all felt quite abstract as a child. These were not the goals I would have set for myself to show things were getting better, that I was calmer and happier and livelier.

So, rather than a variety of coping skills to counteract the biological components of anxiety that were persisting at the start of my graduate career, I housed feelings of resentment, distrust, and skepticism toward all things based in psychological reasoning (not to mention positions of authority). And yet I was able to come to terms with the idea of needing medication – not comfortably or easily, but out of determination to be successful in my school and relationships. Even with a past marked by forced medicalization, I understood that as an adult, I would have more power than I did during my previous experiences. This was a small, rare gem of hope, but it was just enough to keep me going.

What lay ahead the next two months, I could not have anticipated. My mind had believed, perhaps not incorrectly, that being an adult meant I would have considerably more power over my treatment options. My body would belong to me. And this was not just a notion resting in ethical beliefs, but also something I needed to believe to be successful in reentering the world of mental health.

I quickly learned how marked my adult body is once I decided to seek professional psychiatric help. Colonized by special interests, politics, red tape, stereotypes, and stigma, my body was subjected to the choices, decisions, and “reasoning” of the American health care system.

This part of my story is not uncommon to students who have joined their university health insurance plans without fully understanding what is covered (and often more importantly, what isn’t covered). I knew my condition technically constituted a pre-existing condition, but it was my understanding at the time that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) pushed through Congress had alleviated this form of discrimination in health care coverage.

It was true that my university’s insurance plan with Aetna could not deny me coverage to behavioral health services, but they could (and did) make things really difficult by requiring a series of evaluations, referrals, letters, and a processing period, which were most likely in place not to heal but to deter a number of people from moving forward with treatment.

In order to see a psychiatrist, I completed a two-page survey at my campus health center on anxiety and depression, which provided me with a referral to be seen at the campus counseling center. At this particular appointment, I had a formal intake assessment done which resulted in a clinical diagnosis of Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Panic Disorder from the DSM. I also had to be counseled on the options available to me, including ongoing counseling and prescription services at the counseling center or with doctors of my own choosing. I opted to see my own doctor and therapist, which required my university center to file a letter with Aetna that stated I qualified for care outside of the university.

After failing to receive authorization from Aetna a week after my last visit with the counseling center, I called the insurance company directly and learned I would have to provide proof that I had been insured by any health insurance company the past two years.

“What’s the point of this,” I asked the Aetna representative.

“To ensure that this was a pre-existing condition prior to you enrolling in your university health insurance,” she replied.

The overwhelming feeling of helplessness that ensued for weeks, compounded with the anxiety that I already wasn’t able to control, resonated loudly each night as I tried desperately to sleep. This time the anxiety wasn’t a manifestation of an irrational mind – this lack of access really was something to panic over. This was a legitimate emergency, literally a life or death situation.

“I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead

(I think I made you up inside my head.)”

The two lines of Sylvia Plath’s poem “A Mad Girl’s Love Song” replayed in my mind as I sat against the cold bathroom tiles each night in agony. Had I made this up inside my head? How could my suffering be so hard to prove? I pulled myself from the floor and looked at my reflection in the mirror. There I stood, eyes sunken, face paler and dryer than ever before, hair tangled and messy from not having the strength to shower. The circles beneath my eyes looked like they came from angry punches. The insides of my cheeks were raw and swollen from gnawing them down while waiting for each night to pass.

Despite the audacity of the insurance company, what they did was (and is) within the bounds of the law. Had I been unemployed for any reason, or been unable to afford my previous employer’s insurance, I would not have eventually obtained the medication that saved my life. What can be said about the people who don’t share these same circumstances?

The irony behind an adolescence filled with desperate attempts to deny medication and an adulthood consumed with proving my need for medication is not something I ever anticipated. It does, however, depict the unreliable and oppressive system facing many people who have experienced or will experience the world of behavioral health. It is a system that regularly subjects those hurting and disabled to scrutiny, discrimination, and exploitation. And it is a system that meanders its way through “progress” to find the nuances and technicalities that hide within words and ideas.

And this system is perfectly legal.

16 Comments