Lessons from Piccolo Occupy: An Interview with Youth Organizer Ana Mercado

On Friday, February 17, more than a dozen parents, retired teachers, students, and community organizers organized and participated in a sit-in joined by more than a hundred allies in an outside encampment at Piccolo Elementary School, a public school located on the West side of Chicago, IL. The group, Piccolo Occupy, remained in the school–without food and essential medicines–until they received a commitment from Chicago Public School Board Vice President, Jesse Ruiz, to meetings with the full CPS board to discuss the board removing Piccolo and Casals Elementary from the list of schools slated for “Turnaround” and to hear community proposals that would promote educational excellence and maintain community accountability.

Concerned citizens continue to keep pressure on school officials and politicians in the days leading up to the Chicago Public Schools (CPS) Board meeting this Wednesday, which will include an official vote on whether to “Turnaround” ten schools across the city, and the possibility of closing six others. This would entail firing most of the school’s staff and administration, transferring school management to a private agency, and eliminating the legally binding Local School Councils, composed of parents, teachers and community members that govern a regular CPS school. On Monday, February 20, a group of at least 200 people gathered outside of Lakeview High School located in an affluent neighborhood on the North side and marched to Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s doorsteps, urging him to call for an immediate moratorium on school privatization.

This is not a unique issue to Chicago. In fact, this is happening in cities around the country and is the latest iteration of neoliberal educational policies that also inform Bush’s No Child Left Behind, Obama’s Race to the Top (a competitive grant program in which school districts compete for federal funds), and the types of standardized testing initiatives that prioritize test performance over student learning. It also has deep implications for the future of feminist generations.

Ana Mercado, member of Piccolo Occupy and youth organizer with Blocks Together, a membership-based group committed to working on issues of social justice, including privatization, gentrification and criminalization, provides her take on the feminist implications for the Piccolo Occupation and other efforts against school “Turnarounds.”

***

CRS: Hi Ana, what events and steps lead up to the occupation of Piccolo Elementary?

AM: We, at Blocks Together, have been organizing against the school privatization plans of Chicago’s corporate elite (Renaissance 2010) since December of 2007 when we first found out that Orr High School was slated for “Turnaround.” The students organized a walkout at Orr to protest the lack of community engagement in the decision-making process and possible student “pushout.”

Since then these concerns have been confirmed. I’ve witnessed firsthand the dissolution of structures to include parent and community participation and oversight as well as the pushout of students through practices like automatic suspensions and turning students away at the door for minor violations, counseling out and dropping students from the rosters. We knew it was important to work with parents at Piccolo and Casals to stop this from happening again. We connected the parents from the two elementary schools with the Orr parents and youth so they could share their stories.

It came as a surprise to many of the parents that Piccolo and Casals were placed on the Turnaround list in the first place because they both had new principals this year, and usually they allow principals two years to try to improve a school before stepping in. But in addition to this, Casals were both fairing better than the city average after the installation of the new principals.

CRS: So the Board of Education met the Piccolo Occupation’s demand to meet. What do you see as being critical to PO’s success and what does success look like more broadly?

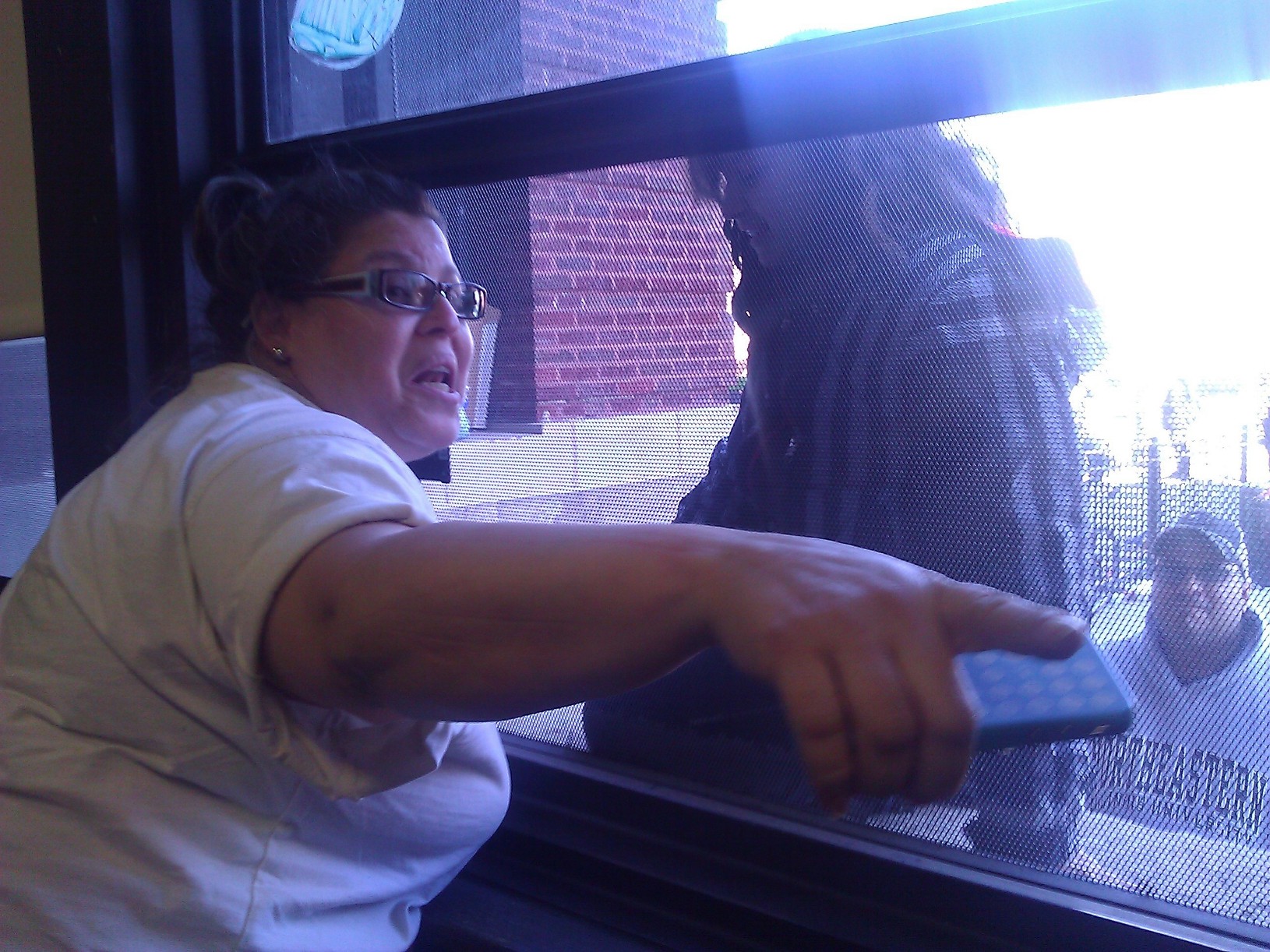

AM: A key component was that it was led by parents and students, and often public school boards try to discredit social justice movements around education by suggest that parents are being “puppeteered” by community groups as a way of delegitimizing dissent. So it’s important to support authentic parent leadership. I think it was also important to take risks–putting our bodies on the line–as a way of bringing more attention to the issue. We also benefitted from some solid work to get the media to pick up on what we were doing. The only reason the board ended up agreeing to meet with us was because of the local and national coverage we were garnering. We had a strong power analysis so we knew this wasn’t about just influencing the CPS board but that it had to affect the mayor and the elites he serves. We wanted to build awareness in the public mind about what’s happening so that we could make the whole system of actors uncomfortable. Where things actually start becoming a movement is when a group of people start doing something (taking a big enough risk) that inspires others to do similar actions. Today we just found out that Smith Elementary decided to a press release inspired by our work at Piccolo and the hope is that other people will understand that they can actually do something about all this and it starts to grow beyond our campaign.

CRS: How do you see your work as informed by your feminist sensibility? And what kinds of feminisms do you draw on in your organizing?

AM: I understand that they get away with these schemes because they play into a narrative that infantilizes or demonizes Black and Latina mothers and grandmothers that are doing this work; these women in leadership positions are about challenging society’s deeply rooted messages (which are often internalized) about what they are capable of.

0 comments