Mentor or Ares?: Some Other Considerations on Mentoring

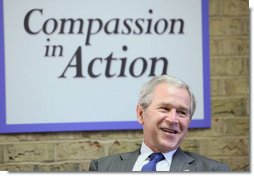

In his 2003 State of the Union Address, President George W. Bush urged “the men and women of America” to mentor. He noted that “[o]ne mentor, one person, can change a life forever” and urged Congress and the America citizenry “to focus the spirit of service and the resources of government on the needs of some of our most vulnerable citizens: boys and girls trying to grow up without guidance and attention, and children who have to go through a prison gate to be hugged by their mom or dad.”

In response to the pressing “need” that he assessed, he vowed that “[g]overnment will support the training and recruiting of mentors” and would invest $450 million in an initiative that would “bring mentors to more than a million disadvantaged junior high students and children of prisoners.”

Bush noted that the “qualities of courage and compassion,” which he apparently perceived as those undergirding a presumed (and shared) American value system, are the principles that foreground social change in America. According to Bush, it is the very enacting of courage and compassion that will increase the number of American adults desiring to become mentors in the lives of those children “lacking guidance and attention” because their parents were somewhere lodged in the American prison industrial complex; curb the number of addicted men and women in need of treatment, who might have also been wedged in the court-house to jail-house pipeline because of drug charges; and spur the development of a “more welcoming society, a culture that values every life.”

Uh, yeah right.

Bush’s rhetorical embellishments established America in the national imaginary—or, rather in his own imagination—as the champion (army?) of “courage and compassion” galvanized to war against drug addiction, failed parenthood, and threats to human dignity.

He went on to deploy the rhetoric of “courage and compassion” (i.e., American’s impatience with “evil”) to buttress his argument that the American Congress and citizenry should put its money behind mentoring and addiction prevention initiatives as well as be prepared to put its money (now estimated at $757.8 billion in total) behind an impending war with Iraq.

So, Bush’s State of the Union speech, which, at its mid-point focused on mentoring, ended with talk of war. The slope spanning the distance between compassion and evil is a slippery one, indeed. To steal the very words that Bush used in his speech to describe Iraq’s alleged maltreatment of its citizenry: If this is not evil, then evil has no meaning.

And here I must draw our attention to the constructive and destructive potential of mentoring (as rhetoric and as praxis), at the place where mentoring and compassion can be transformed into something very different than virtuous. Bush’s words help to illuminate this daunting possibility.

For as much as I am a proponent of mentoring, I have witnessed the praxis of mentoring scandalized and emptied of its good intent. I am a graduate of Fordham University’s and Big Brothers Big Sisters of NYC’s Mentoring Supervisory Certificate program. I have provided short-term consultative services to a federally-funded Mentoring Children of Prisoners Program in southern New Jersey and have even served as grant reviewer for similar programs across the country. I have participated on mentoring coalitions. And, I have benefited from the real-time, transformative mentoring relationships that have manifested in my life. Yet I have also witnessed “mentoring”—as a particular type of relationship formation and praxis—shaped by market interests and made into something very different than a mutually supportive relationship. Indeed, mentoring can also function as a mere catchphrase: a vernacular expression that lacks any depth of meaning and productive materialization in people’s lives.

As in the case of the government, viz Bush, mentoring was/is ironically conceptualized as the means through which social problems in America (i.e., issues facing children of prisoners as if the prison industrial complex is inconsequential) are fixed. Yet, the “problems” that Bush illuminates, which are often triggered by government interventions, or lack thereof, are left un-interrogated.

Or, the rhetoric of mentoring as deployed by the government, viz Bush, as an act that is an outgrowth of the “American values” of courage and compassion even while the same rhetoric was used to advance an unfounded war.

All that to say: mentoring should not be a rhetorical stand-in for compassion when it is the case that some youth “mentors” (corporate class executives whose complicity in business practices might lead to the sustaining of economic depravity in the lives of their youth mentees, for example) lack consideration of the contexts of those whom they mentor. Mentoring can only build up people and systems when it is rightly imagined and executed.

What I am trying to illuminate here is my fear that “mentoring” (or connection) in all of its life-changing potentiality might become doublespeak for disconnection (from the contexts that figure in the lives of others and shape our worlds for good or bad). I am thankful for the mentors in my life—David K. Mensah, Keith H. Green, Mrs. Dunham, Cheryl Clarke, Beryl Satter, James Credle come to mind—but I am also thankful that each of them embraces a vision of the world and a political framework that pushes me in the direction of shared peace and wisdom, unlike Bush, who apparently confused Mentor with the Greek God of War, Ares. Our global community needs incarnations of the former and not the latter.

0 comments