The Shape of My Impact

Sounds to Me Like A Promise: On Survival

(After Audre Lorde: The Berlin Years by Dagmaar Schultz)

“I love the word survival, it always sounds to me like a promise. It makes me wonder sometimes though, how do I define the shape of my impact upon this earth?”

–reflection cut from an early draft of “Eye to Eye: Black Women, Hatred and Anger” by Audre Lorde (Audre Lorde Papers, Spelman College Archive)

I love the word survival. And I hate how we declaim it in our contemporary mouths. Rarely these days do you see the word survival without the disclaimer, not just (survive) and the additive, but thrive. Are we so seduced by the rhyme that we forget the whole meaning of survival? What people most seem to be actually meaning today when they say, “not just survive” actually means not just subsist. Survival has never meant, bare minimum, mere straggling breath, the small space next to the line of death.

Survival references our living in the context of what we have overcome. Survival is life after disaster, life in honor of our ancestors, despite the genocidal forces worked against them specifically so we would not exist. I love the word survival because it places my life in the context of those who I love, who are called dead, but survive through my breathing, my presence, and my remembering. They survive in my stubborn use of the word survival unmodified. My survival, my life resplendent, with the energy of my ancestors, is enough.

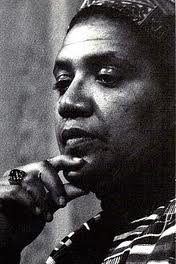

Of course survival is a keyword in black lesbian poet warrior mother teacher, Audre Lorde’s lexicon, and in our memory of her. Ada Griffin and Michelle Parkerson’s biographical film about Lorde is called “A Litany for Survival” after her most remembered and recited poem. “A Litany for Survival” is in fact the poem through which Lorde most frequently survives and is often the last shrine of the word survival on our tongues.

So it is no surprise that Dagmar Schultz organizes her film, Audre Lorde: The Berlin Years, around footage of Audre Lorde powerfully reciting this unkillable poem, stretching the reading through the entire film, but not just because the poem is iconic. The persistence of the poem is appropriate because the film is 100% about survival.

The film is the survival of Audre Lorde, her face given back to us through the many portraits interspersed in the film. The film is the survival of the Afro-German women’s movement as we watch the living founders of that movement, silver-haired and sleek, comment on their own young gumption more than 20 years ago. The film is the survival of May Ayim, a poet and co-founder of the Afro-German woman’s movement who killed herself at the age of 36, four years after Audre Lorde died. I find it appropriate and moving that Ayim gets the most face-time of anyone in the film (besides Audre Lorde) and is also memorialized with a series of portraits, even though viewers who don’t know about Ayim’s life and death, which the film does not explicitly contextualize, may not understand why her bright face is such a crucial image. The film is the survival of an intergenerational ethos, both in the work of Ayim and other Afro-German women, often raised in white families, to make intergenerational ties, and in Audre Lorde’s reminder that “no revolution happens within one lifetime.”

The film is the survival of Audre Lorde, her face given back to us through the many portraits interspersed in the film. The film is the survival of the Afro-German women’s movement as we watch the living founders of that movement, silver-haired and sleek, comment on their own young gumption more than 20 years ago. The film is the survival of May Ayim, a poet and co-founder of the Afro-German woman’s movement who killed herself at the age of 36, four years after Audre Lorde died. I find it appropriate and moving that Ayim gets the most face-time of anyone in the film (besides Audre Lorde) and is also memorialized with a series of portraits, even though viewers who don’t know about Ayim’s life and death, which the film does not explicitly contextualize, may not understand why her bright face is such a crucial image. The film is the survival of an intergenerational ethos, both in the work of Ayim and other Afro-German women, often raised in white families, to make intergenerational ties, and in Audre Lorde’s reminder that “no revolution happens within one lifetime.”

The film is about survival. It is Lorde clarifying that “survival is not a theoretical problem and poetry is part of my living,” and offering concrete advice for the survival of Afro-German women’s groups and literary projects despite the difficulties they face. It is Lorde schooling white women on the urgency of their growth in the face of a 1990s neo Nazi climate in Germany explaining that “it is not altruism but survival” that requires them to act.

I appreciate the existence of this survival film, and in the context of our current forum on Black women’s health in relationship to the academy I think it offers several lessons. One of course, is the place I start, with the reclamation of the word survival. Survival is what some Black women do in the academy, not because they are barely alive, but because we are not supposed to do it, and sometimes we do it anyway. And the way we do it matters.

The survival of Black feminist intellectuals, which happens within or without the academy, is our intentional living with the memory of May Ayim’s suicide after being in a mental institution; our living with the knowledge that as Audre Lorde’s archival papers prove, she was denied medical leave, had to turn down prestigious fellowships (including the senior fellowship at Cornell) that required residency in places too cold for her to live during her fight against cancer. The English Department at Hunter, which recently honored Lorde with a conference 20 years after her death, rejected her proposals at the end of her life to teach on a limited residency basis that would allow her to teach poetry intensive classes for students during warm weather in New York and to live in warmer climates during the winter based on her health needs.

If Audre Lorde’s proposal to teach in a way that allowed her to survive can be denied by the City University of New York, even as she was simultaneously selected as the New York State Poet Laureate, what does that teach us about the value of our bodies in the spaces that tokenize our minds?

And of course this is not unique to Audre Lorde. June Jordan’s records show that even as she was battling breast cancer, UC Berkeley would not grant her medical leave or the breaks from teaching that she repeatedly wrote her administration to request in 2001, months before she died, less than two years after her Black feminist Berkeley colleague, Barbara Christian died. This is not ancient history. This is 21st century economics and the austerity measures, scarcity narratives, and exploitative practices of the university have only gotten more severe with time.

And of course this is not unique to Audre Lorde. June Jordan’s records show that even as she was battling breast cancer, UC Berkeley would not grant her medical leave or the breaks from teaching that she repeatedly wrote her administration to request in 2001, months before she died, less than two years after her Black feminist Berkeley colleague, Barbara Christian died. This is not ancient history. This is 21st century economics and the austerity measures, scarcity narratives, and exploitative practices of the university have only gotten more severe with time.

Let us be clear. Universities keep huge endowments, money on reserve, because they are supposed to keep money. They will always tell you they cannot afford you. They will not spend their money to save the life of a Black feminist. Poet Laureate though she may be. Let us be clear. The universities that we mistakenly label as our bright quirky only refuge for Black brilliance have worked our geniuses to death, and have denied us help when we asked for it. The universities that employed June Jordan, Audre Lorde and so many others, watched cancer eat away at our geniuses, as they simultaneously ate away at black women’s labor. An institution knows how to preserve itself and it knows that Black feminists are a trouble more useful as dead invocation than as live troublemakers, raising concerns in faculty meetings. And those institutions continue to make money and garner prestige off of their once affiliated now dead faculty members.

The university was not created to save my life. The university is not about the preservation of a bright brown body. The university will use me alive and use me dead. The university does not intend to love me. The university does not know how to love me. The university in fact, does not love me. But the universe does.

Survival is what Audre Lorde calls “a now that can breed futures/like bread in our children’s mouths/so their dreams will not reflect the death of ours.” But we, Black feminists of my generation navigating our relationships to the academy, are the children. And we must not ignore the lessons of our ancestors, nor the futures that they have made possible to us through their creativity and persistence.

Should I take a tenure track job anywhere in the world among any manner of quiet or loud racists just to have the security of a health care plan that will become more useful every year because of the stress and ideological violence I suffer on the job? Does it honor my ancestors for me to uproot myself from the communities that have nurtured me that are my realest sources of sustenance and that I must also sustain with my presence and my love? Did Audre Lorde and June Jordan teach in prisons, coffee shops, living rooms and subways so that I could pretend that the university has all the real classrooms and everything else must be a side hustle?

These are the questions I asked myself as I held those denied requests for medical leave in my hands. And again as I turned down tenure track jobs.

And I decided that Audre Lorde is right. Survival is a promise. It is not a promise that any university or non-profit organization can make to me. It is a promise that I make with my currently breathing body to the ancestors who move through it. It is a promise I make in honor of the deaths that make this clarity not only possible, but unavoidable. Survival is a promise. Which is why I am living an experimental intellectual life, dedicated to the creation of accessible autonomous school systems, (in the living room and on the internet—blackfeministmind.wordpress.com) that bring the work of Black feminist ancestors and elders to our communities, directly and committed to creating collective systems of health and mutual support that allow our genius to be accountable to, accounted for, sustained by and shared by the unendowed oppressed communities that are the source of all genius and transformation. Survival is a promise. A covenant between my ancestors, my living communities and this body that is 100% composed of the love that connects them.

I am still working it out. I am uninsured and unaffiliated and living a life that overflows with love shared across space and time. I survive, not because I am barely alive, but because I am flagrantly alive in the sight of my ancestors. The universe loves us. And we sell ourselves cheap when we forget. Our ancestors are teaching us what we deserve. May we never sell our legacy for a mess of ego and scholar-styled swag. May we refuse to exploit our legacy in order to earn more exploitation. May we remember who we are. The shape of Audre Lorde’s impact includes her achievements, her words, her losses and everything she went through that we should not repeat as if we did not know.

I love the word survival. It sounds to me like a promise worth keeping.

24 Comments