Victory

By Erica Cardwell

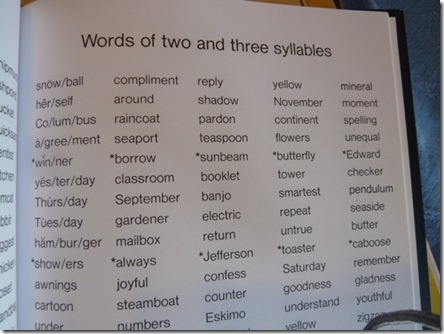

In grade school, we used a phonics book called the Victory Drill Book. It was filled with various words, prefixes, suffixes, and alliteration to sharpen our learning skills through timed phonetic repetition. The book was a hardcover–navy blue, with its name branded in gold on the front. We’d been trained to trace each word with a pencil held horizontally under each pairing or phrase, with a teacher’s aide (someone’s mom, grandma, or church volunteer) pressing an attentive finger upon the stopwatch.

In grade school, we used a phonics book called the Victory Drill Book. It was filled with various words, prefixes, suffixes, and alliteration to sharpen our learning skills through timed phonetic repetition. The book was a hardcover–navy blue, with its name branded in gold on the front. We’d been trained to trace each word with a pencil held horizontally under each pairing or phrase, with a teacher’s aide (someone’s mom, grandma, or church volunteer) pressing an attentive finger upon the stopwatch.

My school was Grace Academy. It was tiny and Christian and taught grades K through 12. Grace was founded by Mary Michael, one of my first heroes. She created the school, and fashioned the curriculum around the priority of Christianity and literacy as necessities for worldly survival. Mrs. Michael believed that words would not only save us, but free us. I understood this later in life, but it was never quite vocalized when I was a girl. Mrs. Michael was a powerful woman, and I believe she loved me despite her periodic references to me as “blackie” or “the brown one.” This wasn’t cloaked endearment or ignorance; this was history. I had entered Grace halfway through my first-grade year. I was the new girl, the brown girl. I could see my difference physically and hoped that no one else would notice.

My Victory Drill Book sessions were held in our small and consistently outdated but well tended library. An old fashioned desk was plugged into a makeshift “corner” where this elementary initiation would occur. The entire experience was, however, quite public. At that moment, no one was going unnoticed. It was always strange to walk into our little library hearing the hum of a friend or classmate, reciting words over and over. In my head, I would say, “I remember that page.” It was all a bit ceremonial and cult-ish in certain capacities and experiences, with individual fortitude in others. I think it caused some children to fumble frequently despite not actually being challenged by the onslaught of syllables.

Perhaps it was some type of prepubescent “performance anxiety.”Grace Academy was determined to instill strong reading skills, even prior to actually being able to read. We were learning about the sounds of the words and not the sound of a sentence, therefore each word was being shaped singularly in our minds and mouths. When students did eventually begin to combine words, make sentences, and read books, the pace would increase and the letters would compound into more complicated phrases. This ritual lasted from kindergarten until third grade.

I have hated tests all of my life. I was not able to name this until I found myself as an eighth grader in tears before an algebra test. My hours of studying still left me feeling unprepared, even after doing multiple practice tests. Somehow, all of the information floated into thin air, and my knuckles and pits would begin to sweat once the test was laid in front of me. But the Victory Drill Book was fun for me because I could determine the progress. I was a voracious reader—my mouth would lift words off of the page before I’d even taken my seat. Letters and punctuation were drinkable, and my positioning was advantageous and adequate for my unique attention span. I could speak as fast or as slow as I wanted. And no one could actually pinpoint my delay…or urgency, for that matter. All of it was up to me. With loosened ribbons in my hair and one untied shoe, I would meet Mary Michael’s standards for my grade level. I was in control. As I grew older, though, this control became difficult to maintain.

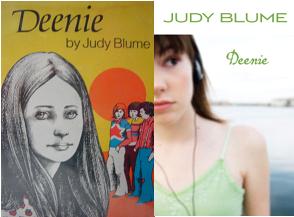

My doe-eyed naiveté continued to serve as an appendage well into puberty. And when it came, I knew that puberty was happening. I knew it because I kept being told that it was.When I was 15, my sister gave me a copy of Judy Blume’s Deenie, urging me to read it, all the while proclaiming “it was banned in schools!” Apparently Deenie was“harmful to minors” due to its sexual content. But for some special purpose, my sister passionately gifted this banned book to her little sister. With a similar passion, I clutched my angst of white girl fantasies and decided to examine Deenie in private. My sister shoved the book into my hands with a weird and earnest admonishment—her eyes prematurely chastising me for not accepting such an evil gift. It’s becoming clearer to me how much of the contradiction I grapple with was learned. I opened the book alone, and immediately felt connected and disconnected to Deenie.

She was white and thin with long flowing brown hair and an early figure. She was loved by everyone—boys, best friends, her family. And simultaneously, everyone wanted to be like her—boys, best friends, her family. Somehow, I treasured her vacant identity. And I related to the attention her long hair and young body gained her. I related despite our differences. I related despite my head of coiled hair. I related because she didn’t look like me. We were similar, not because of our experiences, but based on our inexperiences. I was brown and round (an enthusiastic ballerina!), and also with early breasts for my short body. We had both been ushered into the realm of appeal and access.

She was white and thin with long flowing brown hair and an early figure. She was loved by everyone—boys, best friends, her family. And simultaneously, everyone wanted to be like her—boys, best friends, her family. Somehow, I treasured her vacant identity. And I related to the attention her long hair and young body gained her. I related despite our differences. I related despite my head of coiled hair. I related because she didn’t look like me. We were similar, not because of our experiences, but based on our inexperiences. I was brown and round (an enthusiastic ballerina!), and also with early breasts for my short body. We had both been ushered into the realm of appeal and access.

And I was the last to know.

I was being watched and hadn’t really had a chance to think about why. Deenie, however, was an expert. She would make out with the star football player before his practices, exchanging minimal words, letting him touch her young breasts. For this brown girl, I was within my next phase of social evolution–objectification. And since I was being observed, I suddenly felt obligated to look “right.” And right seemed to be WHITE. At least, that’s what Deenie was. It had become my own unattainable priority. Deenie was my newest fantasy. Judy Blume had quickly succeeded in making me a believer in this fictitious, but terribly true girl. I felt deeply that I was supposed to look like her. Or, not like me.

I didn’t automatically greet my young “blackness” with acceptance, and most times I didn’t want to be a girl. But by this point, I was an early performer, and I knew how to fixate on what seemed physically important…whether or not it was relevant to me. Therefore, I had become an expert at puberty. I would quietly barricade myself within my bedroom and stare at the ceiling with wailing chick rock in the background. Or I would scribble sideways in one of my numerous journals, confusing my parents. I was playing that part, perfectly.

And then something actually happened that I wasn’t prepared for. Deenie’s scoliosis had become so severe that she required a back brace. The beautiful girl with the Barbizon modeling contract was suddenly ugly. She had to wear the brace all the time. There was no way to hide it or not wear it. This was the only way to repair her back that continued to curve in an unhealthy direction. The beautiful girl with the Barbizon modeling contract had to wear a back brace. It couldn’t have been written better. I remember being devastated for her. This whole thing had become extremely complicated and I couldn’t figure out what she was going to do.

But again, Deenie knew. Her hair became her victim as she haphazardly chopped off her precious and valuable locks while staring at the wall as if it were a mirror. When she did turn to the mirror, she screeched every curse word she knew at her deranged and uneven reflection. I mimicked her by pressing my face into my pillow, shouting “damn” and “shit” and maybe even a meek little “fuck.” It upset me that Deenie was falling apart. Her difference was now becoming visible, like me. Suddenly and physically, we had become similar.

One night, as I poured over the book with sleepy eyes, I read the portion that must have summoned the censor’s red flag. I can remember the moment Blume describes, as Deenie reaches down under her covers and finds her “special spot” above her thigh and below her belly button. This was a tender space where she felt safe and comfortable. She was seeking familiarity because everything else had become so foreign and unfamiliar. Finally, her search was deeper and within herself. And again, I wanted to be just like her. So, I set my book down, squeezed my eyes shut, and reached slowly for my tender place. What I found was the nape of my knee. I held tight to its crevice, truly feeling my own definition of safety, hopefully connecting to my protagonist. I had no idea that this was nothing like what Deenie experienced in fiction. However, what I was encountering was fact, and it felt good. I believed in my secret spot. This was perhaps my first foray into actual pleasure and at defining things for myself.

Discovering my pleasure as an adult proved to be a journey of contradictions. My working definition of pleasure was usually outsourced through cranky faces and big hands. I harbored a secret distinction between how I touched myself; how I let others touch me; and my experience with Deenie’s “special spot.” Pleasure floated within these identities, but hardly found a home. I had become really good at fixating on how things were supposed to be, rather than what was actually going on between my legs.

And as I continued to lust for attention, I also continued to overlook my satisfaction. Actual masturbation was a shameful experience—rarely discussed or accepted– but repeatedly maintained. Like good Christian literacy. The untied ribbons and laces still existed, yet I needed to find ways to tie them together and connect them to myself. Again, my familial contradiction was framing my experience. My two selves—Victory Drill master and “special spot” innovator–had to combine forces in order to be “victorious.” It has become clear that these are all parts of the same little girl.

I had been in charge all along.

__________________________________________

Erica Cardwell is a queer romantic, educator, and part time techno-phobe. She is an advocate for spiritual activism, sexual liberation and ambiguous intention. Her work centers on deconstructing the imagery and social perspectives of marginalized and silenced peoples. She writes about art, womanism, girlhood, identity, language, and race . Her essays and reviews have been featured in Ikons Magazine, the London Progressive Journal, and the Australian Dance Collaborative, “the Paper.” In 2009, she was a writer in residence at PAF in St. Erme, France, researching her performance bio, Saintete. And in January of 2012, she was co-facilitator for “Beyond Visibility: Illuminating and Aligning Femmes” at Judson Memorial Church. Currently, she is running a leadership program at the Hetrick Martin Institute for LGBTQ youth of color. Erica lives in the land of make believe in Astoria, Queens. You can read more of her work at www.theomnivorous.blogspot.com.

Erica Cardwell is a queer romantic, educator, and part time techno-phobe. She is an advocate for spiritual activism, sexual liberation and ambiguous intention. Her work centers on deconstructing the imagery and social perspectives of marginalized and silenced peoples. She writes about art, womanism, girlhood, identity, language, and race . Her essays and reviews have been featured in Ikons Magazine, the London Progressive Journal, and the Australian Dance Collaborative, “the Paper.” In 2009, she was a writer in residence at PAF in St. Erme, France, researching her performance bio, Saintete. And in January of 2012, she was co-facilitator for “Beyond Visibility: Illuminating and Aligning Femmes” at Judson Memorial Church. Currently, she is running a leadership program at the Hetrick Martin Institute for LGBTQ youth of color. Erica lives in the land of make believe in Astoria, Queens. You can read more of her work at www.theomnivorous.blogspot.com.

4 Comments