“See Something, Say Something”: The Case of Trayvon Martin

By: Edgar Rivera Colón, PhD

The recent vigilante murder of young Trayvon Martin affords, albeit tragically, an important moment for taking stock in this country of race and the permeating culture of fear that abounds. Young Trayvon was murdered by a man who thought that he was protecting his neighborhood from criminality. In the fear-laden parlance of post-9/11 America, “He saw something and said something.” He took a step beyond this ubiquitous paranoid public safety injunction and murdered a young, promising 17-year-old Black child. Or, did he really go beyond the injunction to “See and say”? Perhaps, he just took it to its next logical step and did what the fullness of paranoia as a civic mandate and political ethos always demands: reactive, punitive and, in these here United States of America, racial violence.

The recent vigilante murder of young Trayvon Martin affords, albeit tragically, an important moment for taking stock in this country of race and the permeating culture of fear that abounds. Young Trayvon was murdered by a man who thought that he was protecting his neighborhood from criminality. In the fear-laden parlance of post-9/11 America, “He saw something and said something.” He took a step beyond this ubiquitous paranoid public safety injunction and murdered a young, promising 17-year-old Black child. Or, did he really go beyond the injunction to “See and say”? Perhaps, he just took it to its next logical step and did what the fullness of paranoia as a civic mandate and political ethos always demands: reactive, punitive and, in these here United States of America, racial violence.

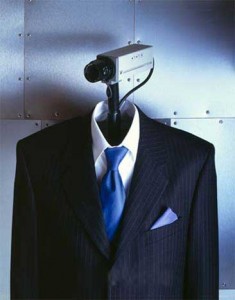

I am tempted to add “mindless” violence in describing what George Zimmerman did to Trayvon Martin, but that would be unfair: it would divorce Zimmerman from the cultural logic of what I call “participatory surveillance” that permeates the American landscape. It would allow all of us off the moral and political hook and render his actions safely to the realm of individual madness. The question is not what was lacking in Zimmerman’s consciousness, but rather what was it full of, teeming with, really.

The sad answer is that the shreds of democratic practices that still endure in our society are slowly being supplanted by the media-managed “impulse” for people to prove their civic mettle by acting like police agents gone wild. Always, of course, for our own collective good. George Zimmerman’s mind was filled with this cultural ethos of “See something, say something” — his mindlessness was well greased by the propaganda anyone using public transportation or consuming media in this country is exposed to incessantly. In one sense, Zimmerman’s acts are the dark side of the broader media apparatus of choice these days in the US — reality television.

Reality television allows all us the positive fantasy and pleasure of watching others and entertaining ourselves through their apparent submission to our surveillance. We see it, talk about it endlessly, and feel so much better for it all. After all, we’re not Snooki and her crew. Our lives are better than that. And, if they aren’t, at least our operatic mistakes and emotional histrionics are not being televised nationally. Well, not quite yet they aren’t. And herein lays the distorted utopian promise of reality television as a national civic culture. To wit: one day there will be 400 million channels available to us and we will all be reality TV stars and perfectly under surveillance at the same time. This is the digital cornucopia that awaits us as a nation at the end of the participatory surveillance road we have embarked upon since 9/11.

Reality television allows all us the positive fantasy and pleasure of watching others and entertaining ourselves through their apparent submission to our surveillance. We see it, talk about it endlessly, and feel so much better for it all. After all, we’re not Snooki and her crew. Our lives are better than that. And, if they aren’t, at least our operatic mistakes and emotional histrionics are not being televised nationally. Well, not quite yet they aren’t. And herein lays the distorted utopian promise of reality television as a national civic culture. To wit: one day there will be 400 million channels available to us and we will all be reality TV stars and perfectly under surveillance at the same time. This is the digital cornucopia that awaits us as a nation at the end of the participatory surveillance road we have embarked upon since 9/11.

George Zimmerman has simply substituted his role as a surveillance entrepreneur (or vigilante in a prior American cultural formulation) for a live action hero. Trayvon Martin lost his life to this culturally propelled substitution. The racial history of our country made this young Black man the logical target of our endless search for enemies within the confines of the “good” neighborhoods, even, or perhaps especially, if Trayvon lived there. The combination of the culture of “participatory surveillance” and the logic of mass surveillance and incarceration of Black and Latino men are literally a lethal combination.

In the long fight for freedom in this country, why does it always have to be the broken bodies of Black and Brown children that must be offered up in sacrifice? The sheer posing of this question calibrates the distance we have yet to walk, suffer, and endure. The cultural logic of participatory surveillance promises more of the same, albeit in high definition resolution. Trayvon and his generation deserve better fates than what our collective fear and continued racial hatred, repurposed after 9/11, are offering them. Perhaps, shutting off our televisions, donning our hoodies, and hitting the streets might be good first steps in crafting something like actual participatory democracy. Showing up to our own lives is a difficult thing to do, but it may be the only thing that saves them.

Author’s bio: Edgar Rivera Colon, PhD, a cultural anthropologist, is the Founding Director of Praxis/Kairos Community Research & Community Mobilization Consultants. Until recently, he was Assistant Professor of Clinical Sociomedical Sciences at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health in New York City.

Author’s bio: Edgar Rivera Colon, PhD, a cultural anthropologist, is the Founding Director of Praxis/Kairos Community Research & Community Mobilization Consultants. Until recently, he was Assistant Professor of Clinical Sociomedical Sciences at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health in New York City.

8 Comments