The Trouble with "Flip-flopping"?

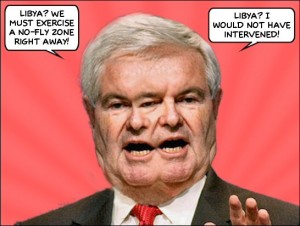

Newt has taken to apologizing, but not for cheating on his wife as she was violently ill or participating in the Clinton witch hunts which cost US taxpayers approximately $70 billion. Rather, he’s apologizing for having appeared in a video with Nancy Pelosi which insinuated that they supported similar efforts to address climate change. Newt is not the first nor will he be the last political figure to be called a “flip flopper”. Mitt Romney is being skewered for his evolving stance on abortion. Even Ron Paul’s “moment of racial clarity” in which he offered a critique of institutionalized racism (a sharp departure from the tone of his newsletter writers) has been called out.

The accusation “flip flopper” has reached such epidemic proportions that it is has become a political epithet. In contemporary poitical rhetoric, it seems to carry a greater threat to one’s character and reputation than being a liar, a bigot, a misogynist, or resolutely out of touch with everyday Americans. Yet basically, flip-flopping amounts merely to a change in one’s perspective on an issue. What does it mean that acquiring new information, taking a second look, and revising one’s opinion are all demonized practices in American political culture?

What makes a good American leader, and by extension what makes a good American? Apparently, someone who remains rigid not only in the face of opposition, but in general. That is, the non flip-flopper.

Recently, I was talking to a friend who revealed that while she liked her job as a pharmaceutical research assistant, her plan was to quit within the year to more intensely explore music. “My parents don’t know yet,” she confessed. She seemed more scared of their reaction rather than the risk of leaving a job with health insurance and a steady paycheck. Another friend expressed something similar when she decided post-culinary school that she liked cooking…at home for herself. She got another degree and started doing non-profit work but not without enduring years of eye-rolling and passive-aggressive commentary. Apparently, there are costs to pay for changing course.

No one is born feminist, and very few of us are raised feminist. As such, the process of coming to a feminist identity always involves rejecting what we know in favor of a perspective that resonates more deeply with us and probably challenges facets of the communities from which we originate. Sometimes friends and family will “remind” me of a perspective I held or something I did prior to embracing feminism. For example, I had a Hooters t-shirt in high school. I wore it proudly. And as much as I have a fierce critique of how dominant images of female sexuality almost always fleece women of their sexual agency, it felt like a bold move…almost feminist. Today, I wouldn’t celebrate a Hooters t-shirt as a feminist artifact. I’d more likely indict it on grounds of enlightened sexism, a form of sexism that celebrates women’s liberation even as it fortifies patriarchy.

Other friends have similarly vexed elements contained in their feminist coming-of-age tales. They too have revealed that others seem to revel in policing one’s present feminism by reminding us either of our historic sexism or more hurtfully of our past experiences of oppression. “So you call yourself a feminist now, well I remember when,” and so on. Even celebrities like Lady Gaga, who grow to embrace the term feminist, face scathing criticism. Their pasts are held up as reminders that feminism was not always part of their identities, suggesting that it is not authentically part of their worldview now. This condemnation is deeply rooted in a loathing of evolution, transformation, flip-flopping. Obviously, then, politicians are not the only folks who are deemed flip-floppers. Perhaps they are just the most public. In fact, the accusation is routinely hurled at anyone who challenges the normative order, feminists especially around issues of gender and sexuality.

Calling someone a flip-flopper is tinged with homophobia. Like sissy or pansy or pussy, flip-flopper seems to suggest that one is not sufficiently rugged. It should come as no surprise that flip-flopper is hurled at queers. For those who pursue relationships over the course of our lives that are not exclusively straight or gay, our intimacy is often stigmatized as adolescent. Apparently, to be a real grown-up, one must decide early on what one is and “do” or inhabit that identity forever, as if our desires were set in life, unchangeable. Yet we know this is not how humans work, not in terms of identity, not for sexual practices, not for food or music or literature. But queerness is indicted on grounds of immaturity and thus inauthenticity.

Freak is another word for flip-flopper. We stigmatize mutability and by contrast celebrate stasis. Consider that “being stable” signifies staying constant (“she’s in a stable relationship”), but its corollary “being unstable” does not simply conjure notions of fluidity or amorphousness. Rather, instability carries particular negative connotations: unbalanced, unsteady, unhinged, disturbed, deranged, dangerous.

Flip-flopper has such rhetorical force that it is used not only by people who want to devalue feminism or queerness, but also by feminists and queers to police one another. I have heard the question posed to feminist colleagues: “How can you call yourself a feminist and fill in the blank?” While interrogating our own and others’ feminisms is a practice aimed at critically recognizing and dismantling privilege, it is also that case that when posed in this way this question is an accusation rather than a query. The criticism rests upon stigmatizing a current stance based on contradictions embedded in one’s biography. Queer friends reveal interest in pursuing intimacies that look rather straight but fear ostracization from queer communities. Even in those groups premised on challenging the status quo there’s often pressure to be consistent.

The term “flip-flop” connotes shifting between one of only two positions. Flop over, and you’re face down. Flip over, and you find yourself face up. There is no in-between in our culture, which is so reliant on gender dimorphism and the sexual binary to make sense of identities. One should fit in one of two categories (male or female, gay or straight, black or white). And one should stay there. Sexism and heteronormativity rely on delimiting the possibilities, and the label “flip-flopper” with all the judgment and antagonism it carries plays right into the hands of those who pathologize evolution and transformation and growth.

I am in no way attempting to recover or defuse criticisms of Newt or Mitt or Ron. The problem with Mitt’s stance on health care reform is not that it seems to have shifted over time. The problem is that the policies he presently supports would, without a doubt, ravage the health of those who are already the most vulnerable, namely poor children. Ron’s anti-racist critique stands in startling contrast to positions he has supported in years past, and it seems like progress. But oftentimes, political flip-flopping has very little to do with substantive self reflection and more to do with electability. Specifically, shifting policy stances emerge in response to stakeholders—political action committees, campaign contributors, and constituents. There are reasons to be skeptical of new perspectives or affiliations, but we should not be skeptical simply because they are new. Instead, we should ask what underlies this stance. Is loyalty and a newly discovered commitment to marriage an offshoot of spiritual zeal or a required position of candidates affiliated with a political party that deploys “family values” as a short hand for ethics, even as the party revels in destroying millions of American families through anti-gay, anti-immigration, pro-incarceration policies?

The question is one of intent: what inspires the change and what work does a given transformation do in the world? In the case of political flip-flopping, it might be that new positions are indicative of yielding to overarching party goals, and this often leads to harm in the world. But flip-flopping aimed at the status quo is oriented towards justice and expanded wellbeing for us all. That being said, I suggest that feminists reject flip-flopper as an accusation in favor of substantive critiques. Attack the stance not the process. Changing one’s mind is not a character flaw, and shifting one’s identity in light of new insight is not evidence of personal defect. In fact, a just world depends on both of these practices.

0 comments