COLLEGE FEMINISMS: Blonde Success: Fact or Myth?

By Ravon Ruffin and James “JP” Miller

Do gentlemen really prefer blondes or has a history of fetishization of “the blonde” by media made it more ideal? Hollywood built a stereotype of beauty surrounding blonde appeal. Aspiring white female actresses found ready made access to hollywood by abiding to this Eurocentric standard, and a legacy of female celebrities since then have been motivated by blonde ambition. Female musicians and actresses alike, depend on the cult of desirability for fame. But too often, desirability means subscribing to a singular standard of beauty, no matter how fleeting. And in our culture, the attractiveness meter typically tips toward the blonde.

Historically, white supremacist ideology located racial purity, nobility, vulnerbility, and ideal cultural beauty in being blonde. Being blonde meant being untainted. And being untainted meant being free of “outside” ethnic contamination. This sentiment was particularly pronounced during Hitler’s Nazi regime and his desire to produce the perfect Aryan race. With the enforcement of the Lebensborn, he stole blonde children and used them in genetic reproduction, and encouraged SS soldiers to procreate with the women of occupied Scandanavian countries. Although, present day media propaganda of the blonde may not be as aggressively targeted, the message remains the same: blonde is a superior socio-political-aesthetic value.

The myth of the blonde is writhe with imaginations of an ideal white woman — too often used for sexual enticement. However, it is the dissemination of this myth into real world relations, which infiltrate the boundaries of ethnicity, age, and social politics, that is perhaps most distressing. Its survival seems contingent upon division among women–the haves and the have nots–and thus the creation of oppositions. Blackness, then, is immediately excluded from this imagination. The blonde myth serves as a constant discriminant. Blonde success thrives on difference amongst women and then devaluing that difference. The complex diversity and integrity that is the woman is undermined by this cultural obsession.

Recent celebrity ambition embedded in the blonde standard of beauty is a mere reflection of the pop cultural obsession America has had for its coveted blonde doe-eyed princess in earlier Hollywood iconography. The 20th century produced a slew of stars adhering to the tropes dedicated to the blonde. Annette Kuhn, Professor of Film Studies (Queen Mary, University of London), makes a division of three film caricatures portrayed within the blonde stereotype in The Women’s Companion to Film (1994): the ice-cold blonde, the blonde bombshell, and the dumb blonde.

The ice-cold blonde is imagined to be the femme fatale shielded by a cold demeanor. These women exhibit an air of cool elegance on screen that is seductive to their male counterparts, but ultimately the source of the men’s demise. The blonde bombshell is believed to embody all things allure, a temptress in the attention of male suitors willing to risk their marriage and money for the pursuit. The ever-pervasive dumb blonde is said to rely on her beauty as opposed to intellect. These tropes appear innocent on screen. However, the fame of many up and coming and existing actresses seem to be both invested with and dependent on these sorts of cultural ideals.

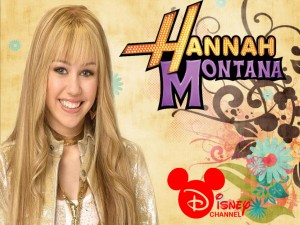

In recent entertainment, we see a combination of these exploits in the music industry, film and television. Network corporations such as Nickelodeon and Disney bank on the aspirations of young girls to be attracted to these exploited images in such projections as Tangled (2010), Hannah Montana (2006), and Zoey 101 (2005). These sorts of representations not only stigmatize things like glasses, braces, and certain types of abilities as “nerdy,” they denounce the value of complex diversity–differences between and among all kinds of bodies and ways of being. This creates a shell of existence for not only the actors and actresses, but the audience.

Blonde stereotypical ideals fuel the regulation of gender appropriated roles and normalization for women. Hair color (whether achieved or birthed) is used not only to perceive intelligence and competency, but to restrict the expectations and varied abilities of female populations. Yet, while those in the starlight arena may bask in the superficial luxury of “Blonde Success,” those “on the ground” with limited resources face the unescapable realities in which blonde culture inflicts.

Blonde stereotypical ideals fuel the regulation of gender appropriated roles and normalization for women. Hair color (whether achieved or birthed) is used not only to perceive intelligence and competency, but to restrict the expectations and varied abilities of female populations. Yet, while those in the starlight arena may bask in the superficial luxury of “Blonde Success,” those “on the ground” with limited resources face the unescapable realities in which blonde culture inflicts.

For example, media output has proven to significantly affect workplace politics. A study (Kyle and Mahler, “The Effects of Hair Color and Cosmetic Use on Perceptions of a Female’s Ability,” Psychology of Women Quarterly, 1996) surveyed subjects provided with a photograph of the same woman pictured with red, brown, and blonde hair, paired with a job application of equal qualifications. The subjects were asked to rate the women’s competency level for each application in conjunction with one of the photographs. The study showed that the same woman, pictured in all the photographs, was scored as significantly less competent when blonde than when pictured with red or brown hair. The problem is, the invasive nature of blonde stereotypes collapses the difference between having blonde hair and being “a blonde.” Blonde then becomes a perplexing dichotomy for Hollywood success and glamour–and real world affliction.

Let’s look at musical sensation Taylor Swift. Onstage she embodies America’s pop princess. Her long blonde tresses and soulful innocence of love deserved and love lost make her marketable to a large demographic of teenage girls and young women. Swift’s hit, “We Are Never Getting Back Together” (Red, 2012), from her latest album shares her experience in a relationship that seemed too good to be true. However, it comes to a head when her lover proves to be a womanizer. In the end, the music video was nothing short of a great time–a great love story that ended prematurely. Swift is revealed as a victim with agency; with good enough sense to be aware of her partner’s infidelity.

However, it is not her lyrics alone that keep Swift on her ideological pedestal. Swift is often put in juxtaposition to the punk-blonde bad girl Rihanna aka “RiRi.” Both women are marketed to the same demographic–however Rihanna’s darkness (read: badness, read: blackness, read: black blonde, read: tainted) makes room for and heightens Swifts divinity. Rihanna’s hit, “Diamonds” (Unapologetic, 2012) delved into her controversial relationship with r&b artist Chris Brown. However, references to consuming alcohol and the recreational drug, molly, paint a picture of haplessness, vulgarity and unscrupulousness. Though many dismiss this reading as having to do with mere representational and recreational [personal] choices, the overarching and ongoing distinctions made between the two simultaneously have much to do with the racialized global imagery and mass-mediated stereotyping.

In Rihanna’s music video for her worldwide hit “We Found Love,” (directed by Melina Matsoukas) she is shown yet again in a tumultuous domestic relationship that is revealed through scenes of her and her lover abusing drugs, violently arguing, and being menaces to the community around them. As Rihanna explores conditional love and lost hope through her music, she is portrayed in perpetual confusion until she finally packs her bags and leaves her unconscious lover behind. A year later, Swift’s video for “I Knew You Were Trouble,” (directed by Anthony Mandler) sings a similar tune (yet much different from her previous works). Coincidentally, this video shares similar qualities in styling and lighting, but more noticeably in the storyline.

In the video, Swift wakes up in the middle of a field and recalls the day before when she met a young man whom she had a short-lived romance. They partied together, overtook a restaurant, and Swift held her lover’s hand as he got the word “love” tattooed on his chest. The video took place in a California-desert area and the two lovebirds never argued until she decided to break up with him. Swift wakes up at the end of the video in an open field once again, unscathed and unharmed, left to get on with her life from the crazy night before. The theme of Swift’s video attests to her control over her decisions and love life; her lover had enough respect for her to treat her kindly for the time they were together, and while Swift confirmed her own convictions about her lover, she was left unharmed and able to “wake up” with the situation handled for her.

In comparison, Rihanna’s video displays her perceived loss of control and confusion; being an accessory to her own turmoil and the importance of an authoritative male “lover” in her life, regardless of how violent and inconsiderate he may be. Not only did Rihanna fight with her lover and do drugs for the majority of the video, she had to make the decision to leave solely for herself and even drag herself back into the harmful atmosphere to make the decision completely. Of course Rihanna, as an artist, had license to tell a different kind of story. But one must wonder how much her own experience with violence and/or personal and historical contexts might shape not only her critical consciousness, but her storytelling. To be sure, there’s a push and pull between the director and the artist, but what was the director thinking? Was she trying to get at Rihanna’s truth? Or, did she feel this particular display of truth would sell better? Intentionality, which is layered, is difficult to know. However, if the director’s intent in any way leaned toward the latter, then we must ask why?

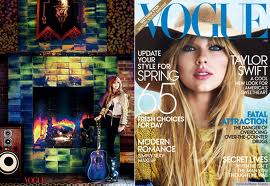

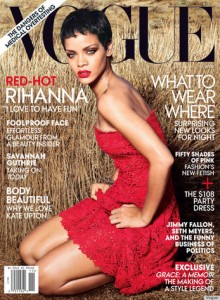

Difference between Swift and Rihanna is further established through media depictions. Both artists graced the cover of Vogue in 2012 (Swift in February and Rihanna in November), an opportunity reserved for the most powerful female entertainers and icons, but the images were strikingly different. Swift’s cover consisted of a headshot with a cool feel and blank, stark stare, along with the caption “Taylor Swift, a cool new look for America’s Sweetheart.” Rihanna’s cover featured the singer kneeling on the ground in a red dress, her shoulder turned to the camera and in the middle of a field. The caption read, “Red Hot Rihanna, ‘I love to have fun’.” Though the images themselves are obviously different, it is the captions that bring attention to the subtle pattern of each entertainer’s branding. Why is Swift always branded as an innocent girl-next door while Rihanna is always positioned as the battered bad girl substance abuser impulsively needing a good time?

Difference between Swift and Rihanna is further established through media depictions. Both artists graced the cover of Vogue in 2012 (Swift in February and Rihanna in November), an opportunity reserved for the most powerful female entertainers and icons, but the images were strikingly different. Swift’s cover consisted of a headshot with a cool feel and blank, stark stare, along with the caption “Taylor Swift, a cool new look for America’s Sweetheart.” Rihanna’s cover featured the singer kneeling on the ground in a red dress, her shoulder turned to the camera and in the middle of a field. The caption read, “Red Hot Rihanna, ‘I love to have fun’.” Though the images themselves are obviously different, it is the captions that bring attention to the subtle pattern of each entertainer’s branding. Why is Swift always branded as an innocent girl-next door while Rihanna is always positioned as the battered bad girl substance abuser impulsively needing a good time?

These scenarios and images are appropriated and normalized through the media’s invasive misjudgment of character and filtering. They feed our mass mediated appetites. Though its been confirmed that Rihanna was assaulted by her on-again-off-again ex-boyfriend and smokes marijuana, these are personal lifestyle decisions–decisions which we should be slow to judge and not be so quick to suggest that ‘Swift would never.’ Tabloids regularly circulate stories about Swifts’ multiple short-lived romances with numerous Hollywood celebrities. And she has already confirmed that her songs are about the different lovers she’s been involved with, but yet she remains “America’s Sweetheart” and avoids being read as a troubled vixen like her pop royalty counterpart.

These scenarios and images are appropriated and normalized through the media’s invasive misjudgment of character and filtering. They feed our mass mediated appetites. Though its been confirmed that Rihanna was assaulted by her on-again-off-again ex-boyfriend and smokes marijuana, these are personal lifestyle decisions–decisions which we should be slow to judge and not be so quick to suggest that ‘Swift would never.’ Tabloids regularly circulate stories about Swifts’ multiple short-lived romances with numerous Hollywood celebrities. And she has already confirmed that her songs are about the different lovers she’s been involved with, but yet she remains “America’s Sweetheart” and avoids being read as a troubled vixen like her pop royalty counterpart.

Swift is our beautiful Venus, the golden locked goddess of love, not the Hottentot, reserved for Rihanna and others. Rihanna’s beauty, even as a blonde, is always countered by sexual and other forms of deviance. So then one must ponder, where does blackness fit into the blue-eyed blonde American dream?

From the previous analysis and comparisons it would seem befitting to say that black makes the difference. Black cannot fully fulfill “the blonde” fetishization, especially since blonde is [wrongly] seen as “unnatural” for women of color. Still, we see black stars on their rise to fame imitating blonde ambition. It’s interesting to note the vast difference in appearance among stars like Nicki Minaj and Beyoncé Knowles, both of of whom began their careers with darker hair. As the limelight grew, there seems to have also been a significant lightening of the skin, perhaps to enhance their blonde ambition. In a recent vacation photo from Cuba, Knowles is pictured in box braids but seems to transform quickly into long golden locks for mass media appeal on stage. And just recently she seems to have cut her hair into a short pixie cut and then an overnight mid length bob.

Could this be possible resistance to the blonde=sexy=success trope? One never knows. We’ll have to check back in in a couple of months.

Nevertheless, the transition between the box braids and long locks suggest a distinction between the private and public realm, which rarely meet. In the case of Knowles, despite all her efforts and interviews about her work in the church during her youth, marrying her teenage sweetheart, having her first child post-marriage, and assuming her husband’s name, occupying the same space that her female counterpart Britney Spears, was initially allowed seems off limits. Spears had the luxury of making rampant appearances in tabloid media without fully losing her crown. The leisure she’s been granted, regardless of both stars arriving on the scene around the same time, highlights America’s fixation and fetishization on/for white blondes. Knowles’ perfectionism can’t help this. And honestly, if the stories were reversed, do you believe Knowles could maintain the same agency she holds today? No. Her blackness makes this so.

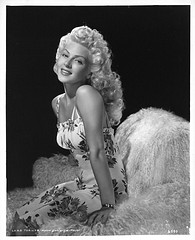

The legacy of Ms. Monroe makes it clear that being a natural blonde is not a criteria for preference, therefore “blonde beauty” is passable for any white woman with a dye job. The issue here is that blonde ambition and blonde divinity permeate our social politics. Moreover, they are divisive. Blonde ambition needs a readily visible binary opposition to exist and thus remains effectively superior in the global imagination as long as all other women, women of color and non-blondes, exist as a negation. This is both destructive and disenfranchising.

So, blonde success, fact or myth? The answer is both. Media mythologizes “the blonde” and we develop blonde ambition. Relative success possibly unfolds. Simultaneously, false assumptions regarding character, intelligence, value, beauty, and complex layering get fossilized and misappropriated in the grander scheme of things.

_________________________________________

James “JP” Miller is a graduating senior with a Psychology major, minor in Business and minor in Gender Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) in Richmond, Virginia. The son of a marine, a large part of his childhood was spent on the island of Okinawa, Japan, where he was exposed to an ethnic-friendly environment as a result of the melting pot quality of the armed forces. Upon his arrival to the states, he was outwardly confronted with discrimination on the basis of race, sexuality and gender difference. These shaped his goals toward the spread of a unified humanity and become a part of the feminist conversation.

James “JP” Miller is a graduating senior with a Psychology major, minor in Business and minor in Gender Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) in Richmond, Virginia. The son of a marine, a large part of his childhood was spent on the island of Okinawa, Japan, where he was exposed to an ethnic-friendly environment as a result of the melting pot quality of the armed forces. Upon his arrival to the states, he was outwardly confronted with discrimination on the basis of race, sexuality and gender difference. These shaped his goals toward the spread of a unified humanity and become a part of the feminist conversation.

Ravon Ruffin, also a graduating senior at VCU, is an Anthropology major and Religious Studies minor. Her piece, “Finding Black Feminism: A Revelation of Black Hair,” was first featured on the Feminist Wire, dealing with the social politics of Black hair. As a Black Feminist, she hopes to advance the conversation of the social politics that dictate our understanding of race relations, gender appropriation and media representation. JP and Ravon plan to expand their group of young minds to create a lasting voice for inclusionary feminisms on campus.

Pingback: Blonde Success: Fact or Myth? (Participation) | CES 101

Pingback: Lovely Links: 9/13/13