I Love So That I May Teach

By Linh Hua

In July 2008, my last formal teacher was brutally murdered. The formulation of that sentence—the recognition of that particular loss—only just recently became possible for me. My memories of the few years following his death are vague at best. I experienced my grief deeply and palpably, feeling the brokenness of my heart all the time. Like many of his students, I grew to love and admire Lindon deeply. His pedagogy rejected a separation of the mind from the body, so to know him as an advisor was also to know dance, food, libation, and song. Having known this abiding combination of love and friendship, I felt sure that it was the source of my immense grief. When one loves, it’s the love that makes loss hurt, not the formal function of the person. Right? In fact, it was precisely the loss of him as my last formal teacher that I did not know I needed to face. It was his impact as my teacher—which I supplanted and confused for the depth of his friendship—that has forever changed me.

When I asked Lindon to direct my dissertation, I was very young. Graduate school was an unfamiliar space to me, and I had little inkling how foundational this single sustained encounter would be. Lindon eschewed his own authority often, if not always, yet students gravitated toward him, wanting to learn more. He had just taken a new appointment at UC Riverside that year, but for nearly two decades prior, he was faculty in the Department of English and Comparative Literature at UC Irvine. There, he built a program in African American Studies and later headed a Cultural Studies reading group. And prior to his leaving for Riverside, a tribute was held to mark the impact of his work on literary studies, cultural studies, African American Studies, and critical theory at Irvine. From him, I learned the stakes of careful reading and the ethics of narrative interrogation. I also learned how to connect from the body and through the heart to the mind.

Unbeknownst to me, I responded to Lindon’s death by teaching with a broken heart. That I taught and wrote critically about love and social justice, a topic that requires passion and a belief in possibility and change, was too much. I separated my mind from my heart so that I could impart to students the tools they would need to change the world for the better, an optimism I no longer held with confidence. In the semester immediately following the murder, my students and I discussed the prison industrial complex and the death penalty after reading Angela Davis and Ruthie Wilson Gilmore. The content of what I taught did not change, but I had changed—I was mourning. I had disconnected my mind from my heart and body, believing I was at least saving the mind. Consequently, I shied away from establishing rapport with students and colleagues and threw myself, instead, into the community, working with non-profits and community action groups, volunteering to organize a press conference and a benefit dinner. I needed to find meaning for my work—a new belief, a new love. Only very, very gradually did I begin to understand the scaffolding that I had erected, the compartmentalizing that I had foolishly understood as progress.

At the time, I relied on obligations to my son to propel me forward into each day. But when I want a photo of him from that time period, I realize that only a handful of shots exist. Only recently did I understand the connection between the absence of those photos and my mourning as negative evidence that I had not fully been present. If I had not been present with my son, how else was I not present? Where did those years go? It’s difficult for me, even now, to form any coherent picture.

Everyone experiences a broken heart in his or her lifetime. I certainly did when my marriage ended. But there was something about losing my last formal teacher—my best teacher—that I needed to acknowledge. I understand how simple and obvious the “realization” is that my work and my words now stand on their own. What took time was recognizing that by mourning Lindon as a friend, I failed to see that his lasting impact on me was, in fact, in jeopardy. Seeing that I had lost my last teacher in Lindon was the turning point in my process of rebuilding. I knew then the depth and quality of my loss: I would not be anyone’s student again. Now, I was someone’s teacher.

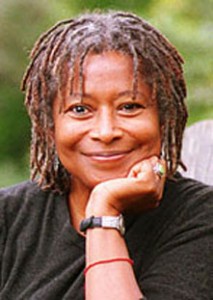

Today, I integrate the classroom and the community in ways that echo trips to Los Angeles with Lindon. I always thought these trips were social, different from café afternoons discussing my chapters. But they weren’t. We were out in the city, seeing how we lived, talking about family, and relating to ourselves in relation to those around us. We talked about the speed of light and Diana Ross. We went dancing. My gradual return to openness was a return to the way of his pedagogy, his insistence that the body carry the mind and vice versa. Our time in the city tested how immediate environments changed our relationship to theory and how we might define it. Drawing on feminist theories of mindfulness from the likes of bell hooks and Audre Lorde, and from womanist spirituality laid out by Alice Walker and Layli Maparayan, I saw how alienated I had become from my life and from my commitment to myself. I was not abiding by Adrienne Rich’s exhortation in 1977 that “[o]nce we begin to feel committed to our lives, responsible to ourselves, we can never again be satisfied with the old, passive way” (“Claiming an Education”). I saw that I had not been living up to my end of the ethical and intellectual contract between teacher and student.

I studied the walls that I had built and used that knowledge, along with lessons I gained from working in the community, to read and write my way out of loss and into love again. I returned to my work with a vengeance, (re)claiming my role in the classroom and allowing myself hope, love, and human connection. I have an obligation to believe in what I teach. I have an obligation to believe in my students. To employ effectively a transformative pedagogy, one has to engage a leap of faith, a hope that what one does in the classroom has real future impact. I did not truly understand how such faith manifests itself until I understood and accepted that I no longer could turn to my teacher.

What does it mean when your teacher is struck down? Teachers don’t live forever, I now tell my students. Learn what you can from them. The split second chance to impact a student is difficult to recuperate once missed. These realizations meant that becoming a teacher for me was a sad, enlarging event. To work through this internal contradiction, I had to give myself permission to forge on with the work that Lindon helped me envision. I had to look forward without the guilt or concern that I had forgotten. I became my own guide, my own ally and cheerleader. This emotional growth, tempered with the recognition and acceptance of loss, presented me with a crucial structure for critical reflection, healing, forgiving, and teaching again.

Today, I incorporate lessons on mindfulness and metacognition to teach students that our hearts and hands are happiest in unison, that politics is not divorced from feeling nor intellect from love. With much seriousness, I teach students in my Feminist Theories seminar to prepare for their campus actions to fail, that real intersectional feminist work is hard. I teach them that this work is neither measured by popularity nor by posters. In fact, it takes deep reflection and accountability, a solid belief that heart, mind, and body need to be in tact—at least in the end. When I ask students to commit to beginning this work of transformation in themselves, I can attest to the difficulty of that process, the need to sustain it and see it as never complete. For my efforts, I have been rewarded with intellectual courage from my students and a healing heart from myself. When I walk into the classroom now, I see Lindon’s pedagogy fully realized. I see every encounter as an obligation to embrace that pedagogy. In this way, Lindon’s pedagogy continues to surround me and care for me, and the experience every day remains awesome and profound.

_________________________________________________________

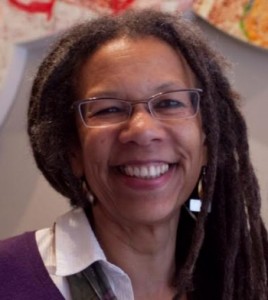

Professor Hua is a Visiting Assistant Professor in the Department of Women’s Studies at Loyola Marymount University. She holds a Ph.D. in English with specialization in African American and Asian American literature and culture, feminist theory, and critical theory, from the University of California—Irvine. She completed her B.A. at the University of California—San Diego, where her thesis examining the cultural invention of childhood revealed an early penchant for challenging social narratives of gender, race, class, and sexuality. From 2002-2005, Dr. Hua served on the Modern Language Association’s Committee on the Status of Women in the Profession, during which time she contributed to developing a national survey on mid-career academic women (Profession 27, April 2009). Dr. Hua was recently awarded the 2012 Joe Weixlmann Prize by African American Review for her article “Reproducing Time, Reproducing History: Love and Black Feminist Sentimentality in Octavia Butler’s Kindred.” Her current work examines feminist autobiography, intimacy, and the place of the erotic in coalition.

Professor Hua is a Visiting Assistant Professor in the Department of Women’s Studies at Loyola Marymount University. She holds a Ph.D. in English with specialization in African American and Asian American literature and culture, feminist theory, and critical theory, from the University of California—Irvine. She completed her B.A. at the University of California—San Diego, where her thesis examining the cultural invention of childhood revealed an early penchant for challenging social narratives of gender, race, class, and sexuality. From 2002-2005, Dr. Hua served on the Modern Language Association’s Committee on the Status of Women in the Profession, during which time she contributed to developing a national survey on mid-career academic women (Profession 27, April 2009). Dr. Hua was recently awarded the 2012 Joe Weixlmann Prize by African American Review for her article “Reproducing Time, Reproducing History: Love and Black Feminist Sentimentality in Octavia Butler’s Kindred.” Her current work examines feminist autobiography, intimacy, and the place of the erotic in coalition.

5 Comments