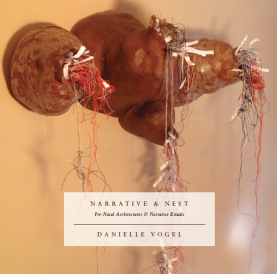

from Narrative & Nest by Danielle Vogel

from Narrative & Nest

by Danielle Vogel

Toward Untraumatizing the Sentence—

If anything comes through in spite of all this, it is a miracle,

and probably no book is born entire and uncrippled as it was conceived.

—Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

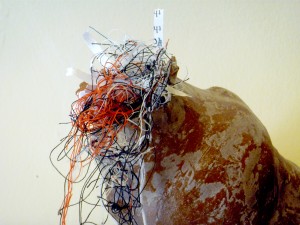

I’m beginning to feel my own voice and body coming into a kind of focus. I think this, in part, because of what I’ve come to understand about the sentence through clay, paper, and thread bodies. These nests have helped me offer form to the problem—and gift—of ethereality and collapsibility. They’ve helped to gestate the body—of the manuscript and also my own—as it awaits its own arrival.

__

I think of the solitude one sits within as one casts a manuscript. I wonder about the writing-space: this strange place at the threshold of the page where I forage sound into shape; where I am exactly here, everywhere, and nowhere at once. No one shares this space with me except my imagined reader and even she is not here with me always. I think of the organ-pipe wasp who frames long mud flutes to reside within. They too are solitary though sometimes two females may build side-by-side, sharing a common wall (Gould 14).

The manuscript builds itself with or without you. Sometimes it kills itself. Cannibalizes. Ghosts. So much so that maybe it never existed. How to convince yourself, yes, I’ve been living in the belly of a hungry ghost. This thing. That must be invoked into the other side of the body.

__

Narrative Midwifery—

Every nest, like the body and manuscript, has a problem it must move through: functionability. When I say this, I mean that the design must reflect the history and purpose of its composition, and this is infinite. I think of Marguerite Duras, “Every book, like every writer, has a difficult, unavoidable passage. And one must consciously decide to leave this mistake in the book for it to remain a true book, not a lie” (28). Sometimes we want to build a nest to sleep within. Sometimes we want our narratives to dissolve. Sometimes we want to live in our nests forever. Sometimes we want to eat them. James Gould and Carol Grant, in Animal Architects, explain, “To begin to understand what goes on when animals build, we need to be aware of the challenges the creatures are trying to overcome” (2-3). I think here of the question. It is the divinatory sill of the question that helps me intuit what needs to be midwifed in voice. By questioning the “problem” of a manuscript, its most poignant story comes into and out of focus. I am able to narrate the flickering by interpreting the effect of my questioning. Working with clay, I think on a question of the manuscript while building architectures for the question. These resulting structures inform the larger body of the work while also functioning as gestation chambers. I hang these swallow-like nests upon my walls. I line and stuff them with bits of manuscripts: failed and developing. I live with them perched in the corners of my home, and I let them teach me about isolation, reparation, and proliferation.

Writing through problems of trauma, I came to understand that these narratives—even the failures—nest in me. While for some authors writing through trauma might dislocate them enough so that they feel as if they are moving toward a kind of healing, it wasn’t until I began to work with my texts outside of the body that I understood how my narratives were performing within me and upon the page.

Researching and practicing somatic trauma therapies, I’ve learned that often, when traumas are processed through language only, the concentrated areas in the body that hold trauma cannot be completely relieved. But when the therapeutic practice includes body-based treatments as well as psychological integration, the treatment is more successful because it integrates the body and its voice. We transgress traumas while weaving a manuscript: they move from the body into the voice; eventually the artifact of the book becomes its own unified body.

Gaston Bachelard, in The Poetics of Space, writes of a “living, inhabited nest;” I am trying to write the living-manuscript so that as it fails in some of its forms, it still convulses in its architecture. I want it to remember its origins (95). I remind myself that not only beautiful things happen in nests. I think of sentences like aquatic breeding grounds that must be anchored to submerged vegetation. In these nests, building material is dived for and brought up to surface. I think of insulating materials below the lip of the line.

__

Later, Bachelard paraphrases and quotes Jules Michelet,

A house built by and for the body, taking form from the inside, like a shell, in an intimacy that works physically. The form of the nest is commanded by the inside. ‘On the inside,’ he continues, ‘the instrument that prescribes a circular form for the nest is nothing else but the body of the bird. It is by constantly turning round and round and pressing back the walls on every side, that it succeeds in forming this circle […] The house is a bird’s very own person; it is its form and its most immediate effort, I shall even say, its suffering. The result is only obtained by constantly repeated pressure of the breast’” (101).

Imagine a book or body or both. Suspended. Imagine the friction of gravity. Each, a husking. A place among places to return. The swellings that precede arrival. Ducts from the body to the page. Ducts from the page to the body. All this to homage the contortion.

Work Cited

Bachelard, Gaston. The Poetics of Space. Boston: Beacon Press, 1994. Print.

Gould, James and Carol Grant. Animal Architects: Building and the Evolution of Intelligence. New York: Basic Books, 2007. Print.

Woolf, Virginia. A Room of One’s Own. San Diego: Harcourt, Inc., 1989. Print.

_____________________________________________________

Danielle Vogel’s textile scroll-works and ceramic book artifacts, which explore the ceremonial gestation of a manuscript as it is written, have been exhibited in galleries across the country. Her most recent collection, Narrative & Nest, is a cross-disciplinary study relating the construction of nests to the writing of books — both as complex sites of composition, habitation, instinct, and narrative. Narrative & Nest has been exhibited in various incarnations at The University of Arizona Poetry Center (May 2012), Abecedarian Gallery in Denver, Colorado (January 2012), the &Now Festival in San Diego, California (October 2011), and will be showing in its latest iteration at Providence, Rhode Island’s the AS220 Project Space in May 2013.

She is the author of Narrative & Nest (Abecedarian Gallery, 2012) and lit (Dancing Girl Press, 2008). Danielle’s creative and critical writing has most recently appeared in Evening Will Come, The Denver Quarterly, Puerto del Sol, and Tarpaulin Sky. She received her MFA in Writing & Poetics from Naropa University, and is currently a PhD candidate at the University of Denver. She lives in Providence, Rhode Island.

Narrative & Nest, in its entirety, can be purchased at: http://daniellevogel.com/

0 comments