Let Our Ears Tingle with Truth

By Keri Day

Victor Hugo powerfully stated, “The guilty one is not he who commits the sin in the dark, but he who causes the darkness.”

There is structural and systemic darkness in this country. Womanist scholar Emilie Townes refers to this structural darkness as cultural productions of evil. Evil as a theological or religious concept is often interpreted as a phenomenon that is discrete from cultural contexts and relations of power. It is often seen as personal. But this is a dangerous assumption. Structural evil provides moral justifications for individual persons to be evil. Structural evil is the grounding of personal evil. Slavery and Jim Crow are examples of structural evil, as these systems allowed America to re-interpret racist institutions as morally legitimate (as the law of the land). The re-interpretation of these two systems as “benign” made it hard for many white Americans to see these systems for what they were: instantiations of evil. Evil is shaped in and through cultural contexts of hegemonic power, which means that we must be willing to understand evil within the cultural matrices of society. As a clergywoman and black feminist-womanist religious scholar, I interpret Mike Brown’s murder within anti-black systems of culturally produced evil. The murder of black men and women every 28 hours in this country is not only unjust but is fundamentally evil.

The language of evil must be reclaimed.

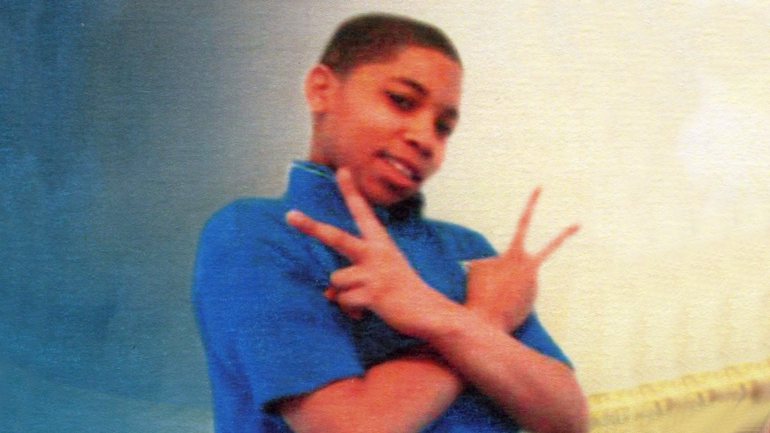

Claiming that the murder of Mike Brown is evil doesn’t allow us to ask what an unarmed Mike Brown did to “provoke the officer.” It doesn’t allow us to presume that Mike Brown’s perceived and/or actual poor choices justify his killing (or him being shot more than six times). It doesn’t allow us to say, “let’s wait until the facts come in” or “let’s be more objective.” Evil doesn’t make room for this. Instead, the language of evil signifies that we must categorically reject and fight against death-dealing darkness and violence. The unarmed black teenager Mike Brown is not responsible for his death, no matter what verbal altercation may have occurred between him and officer Wilson. The murdering of Mike Brown (and the thousands of other murdered black young women and men at the hands of officers) reflects a nation that, theologically speaking, is causing the darkness of structural racism and inequality. In our yet-to-be United States, we live in racist systems and institutions that generate cultural productions of evil.

I am convinced that religious communities have a role to play in helping our society name white racist systems of oppression as evil. These anti-black racist systems and institutions create discrimination through racial profiling and police brutality (i.e., St. Louis has innumerable documented cases of racial profiling among law enforcement within black communities as well as police brutality). They structure slums and ghettos with severe economic, educational, and social disadvantages. And they reinforce the structural darkness out of which riots, protests, and unrest have emerged in America. Consequently, protests are born of the greater crimes of racist institutions and their cultural productions of evil.

These systems are evil and must be categorically rejected and challenged rather than given the benefit of the doubt. Many white Americans would like to insist that institutional racism in the U.S. is mere conjecture. They give our institutions (such as law enforcement) the benefit of the doubt over and against black people who are victimized by these institutions each day. They are sadly mistaken. Institutional racism is a central aspect of America’s past and present. Unfortunately, as Charles Long reminds us, America possesses a hermeneutical dilemma, as this country continues to interpret itself wrongly – as a land of freedom when its history is grounded in the historical and contemporary repression and subjugation of black and brown folks. As reasonable individuals, we normally don’t give the benefit of the doubt where evil is present. So, why do so many Americans offer the benefit of the doubt to hyper-militarized, racist systems such as law enforcement? Because they do not see this institution as mired in evil. This is the central theological problem in America. Americans, in large part, do not see institutional racism as evil.

This is a hard truth. But as W.E.B Dubois defiantly asserts in The Souls of Black Folks, “Let the ears of a guilty people tingle with truth.”

_____________________________________

Keri Day is an assistant professor of ethics at Brite Divinity School and is the author of Unfinished Business (Orbis Books, 2012).

Keri Day is an assistant professor of ethics at Brite Divinity School and is the author of Unfinished Business (Orbis Books, 2012).

1 Comment