“When are we going to wake up?” Anti-Blackness, Police Power, and Profit

By Beryl Satter

“…a black woman, Mrs. Jones, wrote to Mayor Daley because her son was beaten to death by several white cops…over a traffic violation. … a young …mother, Mrs. Anderson, was killed by a young white cop…as she stood screaming for help at her front door. The police superintendent took no action…. What about the black sixteen-year-old boy who was shot in the back? Does your mind wonder which one? Was it the …black youth that was shot near Tilden High school …. Was it the one shot at 77th and Cottage Grove…. Was it the one shot at 19th and Kedzie… or was it the one shot at 21st and Pulaski near the El? … In all of these cases nothing happened to the police. … Did you know that 43 people have been killed by the police in 1970?” — Renault Robinson, “Who’s To Blame for Police Brutality,” Chicago Defender, 7/10/71

The tragic deaths of Trayvon Martin, Eric Gardner, and Michael Brown are among the most recent of a series of murderous attacks on African Americans. The question is why. What is anti-blackness – and how do we fight it. Anti-blackness is a manifestation of a common cultural tendency to create an outsider caste – India’s Untouchables, Europe’s Jews, and Japan’s burakumin are typical examples. And in the modern world, anti-blackness becomes enmeshed in political systems and business models (often working in conjunction) that reallocate resources away from the least powerful.

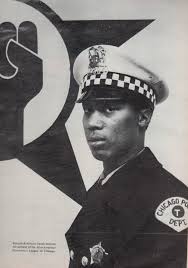

One person who understood the workings of anti-blackness from the inside was Chicago African-American police officer Renault Robinson. In 1970, when Robinson was on the force, a black Chicagoan was six times more likely than a white one to be killed by police. In response, Robinson and other black officers created the Afro-American Patrolmen’s League, dedicated to fighting police brutality. They understood that beatings, arbitrary arrests, and murders of black Chicagoans were caused by many things, from the politically profitable pushing of organized vice into black communities to the psychological biases of individual officers. Police officers’ refusal to provide black Chicagoans with the protection from crime routinely offered to white communities, on the one hand, and their indiscriminate and often violent harassment of black people in general, on the other, left black communities to fend for themselves against combined police and gang terror. Indiscriminate arrests of black people further inflamed white fantasies of blacks as inherently criminal, providing justification in white minds for the quarantine of black communities. Racially segregated housing markets, in turn, enabled clever real estate interests to extract one million dollars a day from Chicago’s captive, housing-starved black neighborhoods.

One person who understood the workings of anti-blackness from the inside was Chicago African-American police officer Renault Robinson. In 1970, when Robinson was on the force, a black Chicagoan was six times more likely than a white one to be killed by police. In response, Robinson and other black officers created the Afro-American Patrolmen’s League, dedicated to fighting police brutality. They understood that beatings, arbitrary arrests, and murders of black Chicagoans were caused by many things, from the politically profitable pushing of organized vice into black communities to the psychological biases of individual officers. Police officers’ refusal to provide black Chicagoans with the protection from crime routinely offered to white communities, on the one hand, and their indiscriminate and often violent harassment of black people in general, on the other, left black communities to fend for themselves against combined police and gang terror. Indiscriminate arrests of black people further inflamed white fantasies of blacks as inherently criminal, providing justification in white minds for the quarantine of black communities. Racially segregated housing markets, in turn, enabled clever real estate interests to extract one million dollars a day from Chicago’s captive, housing-starved black neighborhoods.

Ultimately, Robinson traced police brutality to the existing power structure – in this case, the political machine headed by Mayor Richard J. Daley. Robinson pointed out that the police department was “entirely controlled by the city administration, the white power structure.” Machine politicians appointed racist police superintendents and controlled the racially biased distribution of fire and police department resources. They appointed Board of Education members who thwarted black parents’ efforts to improve their children’s schools. They approved urban renewal plans that pushed black property owners off of valuable land. They allocated public transit and park district funding to favor white neighborhoods. Their actions channeled citywide resources to the machine’s white ethnic base, while isolating black Chicagoans in resource-starved neighborhoods. Their behavior demonstrated how anti-blackness served the economic and political ends of the white power structure.

Robinson did not address how anti-blackness functioned in majority black cities, but clearly the same dynamics are at work, though at a state or federal level. In Michigan, for example, the appointment of “emergency managers” in cities with large black populations (including Detroit, Flint, Benton Harbor, Pontiac, and Ecorse) means that a hefty proportion of Michigan’s black residents are denied democratic self-government. Detroit itself now stands as a showcase for the dilution or complete denial of the black community’s political power, as well as the isolation and demonization of African-American communities. Such actions impede interracial coalitions, thereby clearing the way for political systems to extract black wealth and reallocate public resources in favor of the already powerful.

While Renault Robinson pointed out the broad political and structural components of anti-blackness, he remained convinced that anti-blackness was in many ways exemplified by police terror against black citizens. Police violence enacted a larger cultural belief that black life had no value. Anti-black violence thereby grounded the system of white supremacy that was “destroying this nation from the inside out” by ruining “the credibility of the nation’s basic philosophies,” Robinson explained. It functioned as a “cloak for power and greed,” and it kept the black and white working classes in line, thereby holding “the power where it is…with the money.” He asked in 1972, “When are we going to wake up?” It’s a question every bit as relevant today.

Note: Renault Robinson’s columns appeared in the Chicago Defender between 1970 and 1973.

_______________________________________

Beryl Satter is Professor of History at Rutgers University-Newark. Her most recent book is Family Properties: Race, Real Estate, and the Exploitation of Black Urban America (Metropolitan Books).

Beryl Satter is Professor of History at Rutgers University-Newark. Her most recent book is Family Properties: Race, Real Estate, and the Exploitation of Black Urban America (Metropolitan Books).

0 comments