Who’s Still a Slave? Contemporary Black Women’s Rhetoric, Art, and Global Realities

By Janell Hobson

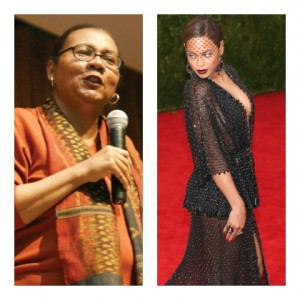

“Are you still a slave?” That was the title of a forum on May 6, 2014 at the New School, featuring black feminist critic bell hooks, writers Janet Mock and Marci Blackman, and filmmaker Shola Lynch. They had gathered to discuss the “liberation of the black female body.”

While several heated debates have since erupted over hooks’ labeling of pop star Beyoncé as a “terrorist” at this event, less commented on was her description of the artist as a “slave,” a conclusion that hooks arrived at because it was suggested that Beyoncé had a hand in fashioning her sexualized image on the cover of Time magazine. Of course, both descriptors – terrorist and slave – seem ill-timed considering the global attention paid to the abduction of 276 girls in Chibok, the northeastern region of Nigeria, who are facing real threats of terrorism and sexual slavery.

This also comes in the wake of recent backlash against comedian Leslie Jones for using slavery (and the historical reality of rape and forced breeding) as a joke on Saturday Night Live, the question “Are you still a slave?” really needs complication. Which slavery are we referencing here? The U.S. version of slave history passed down to us as a too-painful-to-remember yet too-lingering-to-forget record with gaps and silences, often reduced to the nineteenth-century period known as “antebellum,” is still an unknowable site of memory. And yet, it seems that, as contemporary black women, we speak about slavery knowingly, if only to remind ourselves that we still face multiple forms of oppression.

But whether we recall this history through parody (in the case of Jones, who ironically contends that, as a muscularly-built black woman, her “desirability” would be more valued during the slave era) or through academic discourse (with hooks’ implication that there is no “liberation” in confining our bodies to the values of “imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy,” as she accuses Beyoncé of doing), there seems to be a vast historical and transnational disconnect with what slavery means, what enslaved conditions entail, and what it would mean to liberate ourselves under such conditions.

For if “slavery” looks like Beyoncé Knowles-Carter – a black woman who conforms to white capitalist and patriarchal standards of beauty and sexuality but who nonetheless employs mostly women of color, released her most personal solo album, BEYONCE, on her own terms and through her own record company, and also embraces a feminist identity when many other female pop stars in the male-dominated music industry reject it – then what of the black women who have far less resources, especially those who, like the girls in Chibok, are threatened with slavery-like conditions, not in some distant past but in 2014?

For those of us who know the history (and the present-day realities) of slavery, what does it mean to suggest that someone who parlays success out of her own self-fashioned sexualization (and Beyoncé is not the only pop artist to have ever done this over the years; indeed she has modeled her own sexual persona on earlier black female icons – think Josephine Baker, Tina Turner, Diana Ross, and yes, the same Lisa Fischer that hooks now champions for “black feminist liberation”) is the equivalent of someone who is sold against her will, forced to breed and labor tirelessly with no pay, and subject to the harshest punishments we can think of – beatings, rapes, maiming, even murder? Such abuses happened 200 years ago to black women and girls, and it is happening today, with Nigeria counted as one of eight countries with the highest rates of human trafficking in the world, while young black girls are also sex trafficked here in the U.S.

Within a history of slavery, human trafficking, and capitalism – in which the black body is literally the commodity on which capital is built – it’s not surprising when, as black people, we have often championed others who found a way to accumulate wealth on their own terms via their own black bodies. Moreover, some feminists debate the usefulness of the term “slavery” to qualify sex work and sex trafficking, which obfuscates the complex choices that women make when engaging in mobility and “outlaw” sexualities, as such scholars as Kamala Kempadoo, Mireille Miller-Young, and Erica Lorraine Williams have argued when addressing issues of black women in the sexual economy. And if women’s lives are obscured today, imagine how murkier the lives of black women were centuries earlier.

Now, while I believe the “slave” metaphor is used in contemporary black women’s rhetorics as a historical analogy for what continues to “enslave” or “liberate us” – just as I’m sure Leslie Jones doesn’t really believe she’d be better off as a single black woman during the “good ol’ days of slavery” when, as she crassly put it, her “master” would have regularly “hooked her up with a brother” – I do wonder if we would reference slavery so abstractly if we felt the conditions of enslaved black women more concretely in the past and present. The absurdity of Jones’ premise is the punch line, which is why I appreciated the humor more than I was outraged by it; but is it not equally absurd to position a wealthy pop star as a “slave?” If slavery cannot be joked about, even in comedy, should it serve as metaphor for the lives of people who are living comfortably in “imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy,” in comparison to our ancestors?

More than anything, I think we as black women are still struggling with what Lorraine O’Grady once said: “So long unmirrored, we may have forgotten how we look.” Both images of enslaved and free black women have been distorted for so long, we are apt to misrecognize a black woman’s victimization just as much as we might misrecognize her power. Where does the sexualized image of Beyoncé fit in this dynamic since, admittedly, her persona does not connote “liberation” for some, nor does it represent “slavery” for others?

By the same token, we immediately dismiss the power, agency, and choices – however limited – of those ensnared in actual slavery, even though the histories of Harriet Tubman and other enslaved black women demonstrate acts of resistance and subversions. What does it mean to ask “Are you still a slave?” when some of us never accepted that status in the first place?

We have an opportunity to revisit this subject with the new film, Belle, starring Gugu Mbatha-Raw and written and directed by two Afro-British women – director Amma Asante and screenwriter Misan Sagay – which explores the story of a mixed-race woman, Elizabeth Dido Belle. Her history up until now had been frozen in a portrait painted by Johann Zoffany. In telling and visualizing Dido’s story, Asante not only positions a black woman within an eighteenth-century aristocratic family, but she also suggests that, were it not for this woman’s presence in the life of her great-uncle Lord Mansfield, a Chief Justice who ruled on two court cases – the Somerset case of 1772, which prohibited the trafficking of bondspeople out of England, and the Zong Massacre case of 1781, which prevented slave traders from collecting insurance on their dead “cargo” (as the traders on the Zong slave ship attempted when they threw overboard 142 slaves en route to Jamaica) – the humanity of people of African descent would not have been recognized. These two court cases had a massive impact on the international abolitionist movement, which eventually led to the 1807 ban on the transatlantic slave trade and the eventual abolition of slavery in Britain’s colonies in 1833, thirty years before our own country’s ban on slavery. This film, currently playing in movie theaters, is an opportunity to “see ourselves” differently and positioned with privilege and power to impact on world events.

Our black female artists – from Kara Walker’s new public work, “A Subtlety,” exploring the slave legacy around sugar production, to writer Edwidge Danticat contributing to this exhibit with an essay exploring present-day conditions impacting Haitians on Dominican sugar plantations – continue to complicate and expand our rhetorics of slavery. It would be a shame if Belle were dismissed because, as some have already remarked upon seeing the movie trailer, it is “just another slavery movie” in the wake of 12 Years a Slave. However, if we are quick to use “slavery” metaphors to describe our various oppressions, we should also be able to confront art that explores the subject with honesty (or even with humor in the case of Walker and Jones). Perhaps the better question to ask is not, “Are you still a slave?” but rather: “Are you free?”

In Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Baby Suggs tells Denver, when confronting slave history: “Know it and go on out the yard. Go on.” Freedom means knowing our history, recognizing the pain and violence of it, acknowledging its effects in the present, but still refusing to let that history immobilize us and limit our visions of liberation.

REFERENCES:

I am grateful to Tamura Lomax, Birgitta Johnson, and Aishah Shahidah Simmons for their contributions to online conversations that helped me formulate ideas in this work.

O’Grady, Lorraine. 1992. Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity. Afterimage 20 (1): 14-20.

_________________________________________

Janell Hobson is an associate professor in the Department of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at the University at Albany. She has authored two books – Body as Evidence: Mediating Race, Globalizing Gender (2012) and Venus in the Dark: Blackness and Beauty in Popular Culture (2005) – and regularly blogs and writes for Ms. Magazine, including the cover story, “Beyonce’s Fierce Feminism,” in the Ms. Spring 2013 issue.

Janell Hobson is an associate professor in the Department of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at the University at Albany. She has authored two books – Body as Evidence: Mediating Race, Globalizing Gender (2012) and Venus in the Dark: Blackness and Beauty in Popular Culture (2005) – and regularly blogs and writes for Ms. Magazine, including the cover story, “Beyonce’s Fierce Feminism,” in the Ms. Spring 2013 issue.

7 Comments