Feminists We Love: Cheryl Cooky

Cheryl Cooky is an Associate Professor of Health & Kinesiology and Women’s, Gender, & Sexuality Studies at Purdue University. She earned a M.A. and Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of Southern California (Los Angeles), where she also earned a Graduate Certificate in Gender Studies. She also earned an M.S. in Sports Studies and a Certificate in Women’s Studies from Miami University (Ohio) after earning a B.S. in Kinesiology from the University of Illinois (Urbana-Champaign).

Cheryl Cooky is an Associate Professor of Health & Kinesiology and Women’s, Gender, & Sexuality Studies at Purdue University. She earned a M.A. and Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of Southern California (Los Angeles), where she also earned a Graduate Certificate in Gender Studies. She also earned an M.S. in Sports Studies and a Certificate in Women’s Studies from Miami University (Ohio) after earning a B.S. in Kinesiology from the University of Illinois (Urbana-Champaign).

For the past ten years, Cheryl has been committed to researching sex, gender, and feminism, publishing in Journal of Sex Research, Feminist Studies, the Journal of Sport & Social Issues, and Contexts: Understanding People in Their Social Worlds, among other texts. Additionally, Cheryl was a Principal Investigator for “Gender and Sport in Montenegro,” the first ever evidence-based study of gender and sport in Montenegro, a collaborative project with the Women’s Sport Foundation that was funded by the International/Montenegro Olympic Committee and United National Development Program.

In 2010, Cheryl and Michael Messner co-authored “Gender in Televised Sports: News and Highlight Shows, 1989-2009,” a groundbreaking report published by the University of Southern California Center for Feminist Research. The report revealed that women’s sports only garnered 1.6% of airtime on Los Angeles’ three network-affiliate sports news programs. Additionally, the report revealed that women’s sports only received 1.4% of airtime on ESPN’s SportsCenter. Since its publication, the report has been downloaded more than 3,500 times in nearly 70 countries.

Due to the impact of her work and research, Cheryl has been the recipient of numerous honors and awards, including the Purdue University Title IX Distinguished Service Award, the Purdue University Difference Makers Award, the Dorothy Harris/Women’s Sports Foundation Dissertation Scholarship, and the Haynes Foundation Dissertation Fellowship. Cheryl was also an Honorable Mention for the Sociology of Sport Journal Article of the Year Award for “If You Let Me Play: Young Girls’ Insider-Other Narratives of Sport.” Cheryl has also been invited to present her research at California State Polytechnic University, Hanyang University (Seoul), the International Congress of Sport Sciences, the Women and Gender Studies Linda Arnold Carlisle Professorship Lecture Series, and the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women.

********************

TFW: You and I first met when you came to Purdue University in 2009. Just four years later, you earned an early tenure. First and foremost, congratulations! Second, I’m hoping you can talk a bit about the challenges you faced during your promotion process, especially regarding your gender. Additionally, in what ways has feminism helped you overcome those challenges?

First let me say thank you Heidi and to The Feminist Wire for selecting me as a “Feminist We Love.” It is truly an honor to be acknowledged in this way and to be among this amazing group of feminist women and men that you all love!

The challenges I faced are probably similar to the challenges any academic faces both within the discipline and their home institution; the challenge of getting published, of having one’s work acknowledged by her colleagues and peers. However, I also faced a unique set of challenges given my joint appointment across two different colleges and departments (at Purdue, Health & Kinesiology resides in the College of Health & Human Sciences, and Women’s Studies resides in Liberal Arts). For example, there was one project where I was solicited to conduct research on gender and sport participation in Montenegro with the UNDP, the Montenegrin Olympic Committee and the Women’s Sport Foundation (which will be published as a Women’s Sport Foundation report later this year). The challenge was having this explicitly feminist research—the goal was to identify barriers and facilitators to women’s participation—recognized within the institutional structure of my university as “research.” This was in part due to the non-traditional mechanism by which the project was funded and the advocacy-based nature of the study. Having the appointment with Women’s Studies provided a group of feminist peers and colleagues who supported my work; however, the role of academic programs in the tenure process at my university was negligible. So, this feminist support was primarily personal rather than institutional. Having said this, I was fortunate to have a number of external colleagues and mentors within my field who are strong feminists. I often turned to them for support, folks like Mike Messner, Don Sabo, Shari Dworkin, Mary Jo Kane, and Nicole La Voi, among others. Having feminists both within and outside of my institution was quite helpful in negotiating the tenure terrain—both from a policy and procedures standpoint, as well as from a mental health perspective! I know there are men and women who are the only feminists on their campuses, so I feel fortunate to have had these networks to rely upon.

TFW: Just three years ago, USC’s Center for Feminist Research published the groundbreaking report you co-authored with Michael Messner, Gender in Televised Sports: News and Highlights Shows, 1989-2009. In the introduction to the report, Diana Nyad wrote,

TFW: Just three years ago, USC’s Center for Feminist Research published the groundbreaking report you co-authored with Michael Messner, Gender in Televised Sports: News and Highlights Shows, 1989-2009. In the introduction to the report, Diana Nyad wrote,

Women’s athletic skill levels have risen astronomically over the past twenty years in sports from basketball to volleyball, from swimming to soccer. It is time for television news and highlights shows to keep pace with this revolution. I can only hope that, five years from now, when this study is conducted again, it will find a substantial number of women among the ranks of sports news and highlights commentators, and that they, along with men commentators, will have joined the Twenty‐first Century by reporting fairly and equitably on women’s sports. The coverage today misrepresents both the participation and the interest in women’s sports across our population at large.

Based on your own observations, have you seen the kind of progress you hoped for regarding sports news and highlights programming since publishing the report?

While I do hope that the televised news media will reflect the increased participation and interest in women’s sports in the U.S., the reality is that change happens quite slowly and does not necessarily occur in an upward fashion. As in many social institutions, women in sport have been subject to a backlash in this regard. In our research, we found that over the past 20 years (1989-2009), the televised news coverage of women’s sport was the lowest ever in 2009! While the broadcast coverage of women’s sports has increased (for example, ESPN began broadcasting the entire, 64-game NCAA women’s basketball tournament in 2003), the news coverage of women’s sports has lagged behind. In our study, the women’s basketball tournament, arguably one of the most popular women’s sports, garnered only 6 minutes of coverage on ESPN’s SportsCenter (most of it on the scrolling ticker at the bottom of the screen), while the men’s tournament had over 3 hours of coverage!! At the same time, we did find that there were fewer instances of the sexualization and trivialization of women’s sports over the 20-year time frame. The sports media play a powerful role in shaping the interests of viewers and fans—which has real implications for the success of women’s sports. We will begin data collection again in 2014. While I do hope it has improved, quantitatively and qualitatively, I remain cautiously optimistic.

TFW: A couple years ago, you visited The Tucker Center for Research on Girls & Women in Sport at the University of Minnesota to discuss the report. During part of your discussion, you spoke about women being “trivialized and sexualized” in sports magazines, particularly in the 1990s:

When I was a Graduate Instructor for your Introduction to Women’s Studies course at Purdue, one student commented, “Men are sometimes sexualized on the covers of sports magazines, too!” Can you talk a bit about the differences between the ways in which men and women are sexualized in sports magazines?

This is a complicated issue, because it touches upon some of the tensions between Second and Third Wave perspectives on sexuality in popular culture. Many young people today see these images, or in the case of female athletes, actively produce these images, as a form of empowerment. Many female athletes say that they appreciate being able to celebrate their femininity and their athleticism. While I would not deny their experiences of empowerment, or students’ readings of these images, the difference for me is that given the lack of coverage of female athletes playing sports, seeing female athletes primarily in sexualized ways does not challenge broader gender ideologies. And while men’s bodies are becoming increasingly sexualized in consumer culture more generally and in sport specifically, I would argue this is not an example of a kind of equal opportunity sexism, given that we consistently see men participating in sport, being athletically dominant and competent. Perhaps the sexualization of female athletes in the media would be less problematic for feminists such as myself if there were more opportunities to see female athletes playing their sport and more diversity among the images we see of female athletes. However, even if this were the case—it is important to note that the sexualization of female athletes reinforces heteronormativity and operates to closet lesbian and straight athletes who do not wish to reproduce or promote these images in their self-presentation. The media coverage surrounding Brittney Griner (formerly a Baylor basketball player now with the Phoenix Mercury) is a illustrative example of how women who do not conform to heteronormaitve femininity—especially within the world of sports—are ostracized and marginalized by the mainstream sports media and by many sports fans.

TFW: Which recent headlines coming out of the sports world are fascinating you? Of course, I’m thinking particularly about the Aaron Hernandez case and the nearly 30 arrests that have involved NFL players since Super Bowl 2013. How does gender play a role in these or other cases and the responses to them?

TFW: Which recent headlines coming out of the sports world are fascinating you? Of course, I’m thinking particularly about the Aaron Hernandez case and the nearly 30 arrests that have involved NFL players since Super Bowl 2013. How does gender play a role in these or other cases and the responses to them?

In my research, I focus on how the mainstream print news media “frames” controversial issues in sport and what those media frames tell us about our culture in terms of gender, race, sexuality and power. My colleagues and I have examined the Don Imus/Rutgers University controversy (the infamous “nappy-headed hoes” insult directed at the Rutgers women’s basketball team following the 2007 NCAA championship game), the controversy surrounding the mis/treatment of Caster Semenya (the South African track & field athlete who was subjected to “gender verification” testing during the 2009 World Track & Field championship), and the most recent project focuses on the media frames of the Jerry Sandusky/Penn State scandal.

This research entails a systematic content and textual analysis of hundreds of news articles on the controversies wherein we examine the articles for close to 100 different codes. For the Penn State scandal, we had nearly 800 articles in our sample, so it’s quite a bit of work, but it is telling in the types patterns that emerge. Our research team is interested in what exists outside the frame, or in other words, what doesn’t get talked about or covered in the news article. These silences and who or what is rendered invisible within the coverage often is more telling that what is covered. For example, in the controversy surrounding the gender verification testing of Semenya, we compared news coverage in the U.S. to that in South Africa and found that the U.S. media “medicalized” sex/gender and positioned sex/ gender identity as determined primarily through biology, whereas South African media drew upon more fluid and social/contextual understandings of sex/gender wherein biology was irrelevant and instead personal, familial or cultural definitions superseded the results of any “scientific test.” It was critical to situate these media frames of sex/ gender within broader discourses of race, nationalism, the specific histories of colonialism, scientific racism, as well as the history of sex testing of female athletes in sport.

TFW: During an interview with Michigan Radio, you discussed financial, cultural, and emotional investments in certain sports and sports programs. Along those lines, you talked about the “cultural silence” at both the individual and institutional level that manifests itself during times of scandal in sport. You also suggested that we ask about the role economics play in collegiate sports regarding the framing and understanding of certain incidents like the Penn State case. Can you talk a bit about the role gender plays in this context?

After posting this interview on Facebook, I was invited by Michael Giardina to contribute to a special issue on Penn State published in Cultural Studies <=> Critical Methodologies. In that piece, I embarked on developing a theoretical framework for understanding the contradictions and tensions between how we’ve (feminists) conceptualized “giving voice” as a type of empowerment for those who have been marginalized with the ways in which institutions and dominant groups often use silence as a way to maintain power and privilege. It’s the “speaking out” versus silencing that I am interested in exploring. While power may be conferred by having one’s experience, one’s voice, one’s reality given space to be heard, power is also exercised through the ability to not speak and to silence one’s own reality—or at the very least render it invisible so as to maintain one’s (here an individual’s or institution’s) position within power hierarchies. I think feminist scholars should continue to devote attention to those spaces where dominant group’s use silence/invisibility to maintain power. The use of silence works not only to marginalize subordinate groups, but often operates to maintain hegemony and dominance.

In concrete terms, with the Penn State scandal, I can’t help but wonder to the extent to which the controversy would differ (both in how it was experienced by all those who were involved—including Coach Joe Paterno, Assistant coach Mike McQueary, former President Graham Spanier, former Athletic Director Tim Curley, etc. and in its mediated version) had Jerry Sandusky’s victims been young girls instead of young boys. I would argue that the gender of the victims impacted how Sandusky’s victimization of young people was understood and may have been one of many factors as to why silence was upheld for so long by so many people.

For me, though, the salience of the Penn State scandal resides in the culture of football and the culture of Big Time sports on college campuses, which as a number of scholars like Mike Messner have argued, represents an institutionalized patriarchy wherein hegemonic masculinity is reproduced and reaffirmed.

TFW: A couple years ago, you were interviewed by the Journal & Courier (Lafayette, IN) about the participation of girls in football, which is an especially controversial topic. My daughter played flag football in 2011, when she was just 5-years-old, and she was only one of two girls playing in the entire league. What are your thoughts about women and girls playing football?

TFW: A couple years ago, you were interviewed by the Journal & Courier (Lafayette, IN) about the participation of girls in football, which is an especially controversial topic. My daughter played flag football in 2011, when she was just 5-years-old, and she was only one of two girls playing in the entire league. What are your thoughts about women and girls playing football?

First, in the spirit of full disclosure, I must confess that I am a college and professional football fan. I have an autographed jersey of former Chicago Bear Brian Urlacher and had the opportunity to meet another former Bear and Hall of Famer Dick Butkus and have his autographed picture and jersey hanging on the walls in my house. Having said this, your question raises a complex issue, because honestly I’m not sure how I feel about men and boys playing football. While I enjoy the sport as a fan, as a feminist I feel deeply conflicted about the pleasure I experience watching the game, given the realities of the sport. The incidence of concussions represents what feminist scholars have referred to as a “cost of masculinity” and is especially problematic. And in many ways, football is a site for a host of issues related to the reaffirmation of hegemonic masculinity, male privilege and homophobia. So, as a feminist I have to ask, is access to a sport that historically has served to reaffirm and maintain masculinity and male privilege the kind of feminist equality we should strive toward? At the same time, I recognize that participating in a sport that has this strong historical link to hegemonic masculinity can serve as a challenge to the gender order.

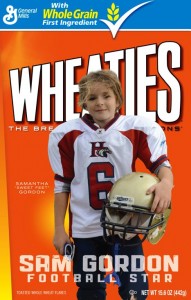

I do find it interesting, and not at all coincidental that the NFL season plagued by news reports and medical studies on the incidence and impact of concussions in football is also the season where we saw football phenom Sam Gordon celebrated by the NFL and appearing on NFL GameDay Morning and appearing on the Wheaties cereal box.

The NFL has made attempts to reach out to girls and women with various marketing efforts including “101” events where NFL teams invite fans, mostly female, to learn the sport and meet the players, and USA Football has programs to encourage mom’s to coach youth teams (given the lack of women who coach youth sports, especially football). Ultimately, it is in these moments of crisis (the concussion controversy) wherein counter-hegemonic spaces are created wherein a disruptive/ transformative potential may take hold (eliminating hard hits, establishing stronger rules to prevent hits to the head, etc.). To alleviate any threat posed in these moments of crisis, institutions often accommodate these challenges by incorporating those groups that may actually benefit from a challenge to the structure or culture of the institution. I see this at play in the contemporary context of football.

TFW: Title IX, the law requiring gender equity in educational programs that receive federal funding, turned 40 last year. In “Olympic Games Inch Closer toward Gender Equity,” David Ebner points out that women won the majority of gold medals for the United States and Canada. Additionally, women were the majority athletes representing both countries in the Olympics, which is a first for the United States. Scott Blackmun, CEO of the U.S. Olympic Committee, attributes this to the impact of Title IX. Do you agree?

While Title IX could be credited with shifting the cultural acceptance of female athletes and with expanding opportunities for young girls and women in the U.S. to compete in sports thus increasing the talent pool in women’s Olympic sports competitions, I would caution against viewing the participation of women at the Olympic games as the sole indicator of equality or equity in Olympic sports.

As with any measure of equality, it is important to consider not just participation of women in an institution but other factors such as representation in key leadership roles, media coverage, salaries of coaches, sponsorship dollars, endorsement deals, team budgets and so on. One controversy that made the news was the women’s Japanese football team flew economy class to the 2012 Olympics while the men’s team flew business class (despite the women’s team had more successful than the men’s). What we need to consider is not only the numbers of women participating in sports, but how resources are distributed, who’s in positions of power to make decisions about the distribution of those resources, who or what is being valued in the cultural discourses surrounding women’s sport participation and that is where the work needs to continue to be done. The Women’s Sport Foundation publishes reports for every Olympics, which include quantitative descriptive statistics on participation trends among athletes and within governing bodies. The 2012 report will be available later this year (click here to download the 2010 report). The Women’s Sport Foundation and other research and advocacy groups are helping to place the spotlight on these issues.

TFW: Further, in the same article, you state, “The revolution is incomplete.” Can you talk about what our nation needs to do in order to achieve more gender equity in sports?

TFW: Further, in the same article, you state, “The revolution is incomplete.” Can you talk about what our nation needs to do in order to achieve more gender equity in sports?

In the Contexts article to which you refer, my colleague Nicole La Voi and I argued that there are “persisting forms of inequality” that continue to plague women’s sports, which I also mentioned in the response above. The lack of women in administrative and decision-making positions in sports organizations, the lack of media coverage of women’s sports, and homophobia are issues that we need to address that do not fall under the jurisdiction of Title IX. While women are participating in sports, we need to radically change the structural organization of sport and the cultural meanings associated with it for major changes to occur. And while there are moments when these shifts do occur, feminist struggles for equality in sport, and in other social institutions are ongoing. In other work, I’ve argued for the elimination of sex segregation in sports, the elimination of the commercial imperative in sports. Of course, as sports are not separate from society, any changes to sports require changes to our broader culture—or conversely changes to sports helps shift the broader culture. In other, changes must occur both within and outside of sports for any meaningful goals towards equality and equity to occur.

Thank you again for recognizing me as a “Feminist We Love.” It’s been a pleasure to have this dialogue.

Suggested Links:

Cheryl on Title IX

Cheryl on the 40th Anniversary of Title IX (Audio)

Cheryl on Stereotypes in Women’s Sports

Cheryl on Women’s Soccer

Cheryl on Athletic Scandals (Audio)

0 comments