What You Don’t Know Can Kill You: Race, Class, and Access to Genetic Cancer Testing

By Duchess Harris and Christine Ohenewah

When Professor Harris was in law school, she gave a presentation in her “Feminist Jurisprudence” course on a New York Times article, “Judge Invalidates Human Gene Patent” published March 29, 2010. She ended with the question, “What if Myriad Genetics wins their appeal?”

At the time, the ACLU and the Public Patent Foundation at Cardozo Law had joined with patients and medical organizations to challenge Myriad Genetics, a company that held patents on the genes linked to breast and ovarian cancer. The plaintiffs argued that the patents stifled research and testing options. Myriad Genetics, however, argued that isolating DNA from the body transforms it and makes it patentable.

The judge ruled that the patent was improperly granted because it infringed on the “law of nature.”

John Ball, one of the plaintiffs who is the executive vice president of the American Society for Clinical Pathology, stated that the Judge’s decision, “…is good for patients and patient care, it is good for science and scientists.”

True. It does seem like isolating a gene to make it patentable is a lawyer’s trick that circumvents the prohibition on direct patenting of the DNA within our bodies.

Myriad then decided to appeal, and won. But ever since Harris’ law school presentation three years ago, she hadn’t thought much about the case until just recently when we saw Angelina Jolie on the cover of People Magazine.

As most people know by now, Angelina Jolie used Myriad’s test. The company is currently selling this test at a cost of more than $3,000 to look for mutations in two genes—BRCA1 and BRCA2—in order to determine if a woman is at high risk of developing breast and/or ovarian cancer.

Jolie opted to receive the test because of her family history. Both her mother and maternal grandmother died of ovarian cancer—strong evidence of an inherited, genetic risk that led the actress to have both of her healthy breasts removed in order to avoid the same fate. And just this past Sunday, May 26th, her aunt Debbie Martin died at the age of 61 after her battle with breast cancer.

In an Op-Ed piece in the New York Times, Jolie wrote:

“The cost of testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2, at more than $3,000 in the United States, remains an obstacle for many women.”

That obstacle looms especially large for women of color. On May 14, 2013 Lynnette Holloway wrote an insightful piece entitled, “Angelina Jolie’s Double Mastectomy: What Black Women Can Learn.”

She outlined that on average, African American women have about the same risk of possessing an abnormal BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene as white women. But research continues to show that non-white women are less likely than white women to receive genetic testing.

Staying alive is now an issue of “class politics.”

Denene Milner in Clutch Magazine further breaks it down:

“The test, alone, would be completely inaccessible, to, say the grocery store worker who brings home a paltry $400 a week after taxes, which makes it hard for her to afford even a simple mammogram. And trust: the school janitor, or the sister at the McDonald’s drive-thru or your auntie answering phones at that secretarial job wouldn’t be able to secure the three months needed to have her breasts removed, heal from the surgery and then go back under the knife for reconstructive surgery and implants—no matter how many of the relatives that came before her were diagnosed with, treated for or died from breast cancer. Those who lord over blue-collar workers aren’t nearly as understanding as, say, a Hollywood producer or a company president who can spare a top manager?”

Myriad’s cost for BRCA gene testing presents an undoubtedly unfair disadvantage to any woman outside the upper middle class who’d like to be tested. So far in the heated debate over the company’s patenting of the gene, the issue of cost has been very well established.

Yet there are further implications tied to class that are beyond economic standing. Class is impacted by history and culture, which means that white women with wealth often have a certain level of trust in the American healthcare system that Black women don’t. Our history with bioethics has not been so ethical, and a Black woman who could afford to have surgery at the Pink Lotus Breast Center in Beverly Hills might be apprehensive.

Consider that African-American women are more likely than all other women to die from breast cancer. Research presented in April at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research has shown more insight as to why this disparity exists.

“The results seem to indicate that although African-American women are more likely to be diagnosed with less treatable subtypes of breast cancer compared with white women, it is not the only reason they have worse breast cancer mortality,” said Candyce Kroenke, M.P.H., Sc.D., research scientist at Kaiser. “African-Americans with breast cancer appeared to have a poorer prognosis regardless of subtype. It seems from our data that the black–white breast cancer survival difference cannot be explained entirely by variable breast cancer subtype diagnosis.”

Recent genetic profiling has suggested that not all cancer subtypes are created equal and both the tumor makeup and methods for treating them may vary by race. Others maintain that factors such as poverty, silence, and racial inequities—not genetics—are responsible for high mortality rates. Their efforts have focused less on treatment than on awareness and eliminating cultural barriers to seeking care.

These issues are relevant; yet they do not address Black women’s legitimate fear of the health system ―and for good reason.

Take the case of Henrietta Lacks, an African American woman who died of ovarian cancer in Baltimore, Maryland in October of 1951. Lacks unknowingly had the cells from her tumor removed and publicly displayed at a press conference by researchers at Johns Hopkins University. The cells taken exhibited a unique vitality, and unlike other cells before it, did not experience cell death. In presenting the test tube that carried Lacks’s cells, culture researcher Dr. John Gey announced that a new era of research had begun—one that someday could produce a cure for cancer. As sociobiologist Hannah Landecker observed, these cells, known as “HeLa,” continue to be used, explained, exploited, and narrated, in the popular scientific press as well as through film and television.

Lacks and her family were never informed that her cells were used for research until 25 years after her death.

Her story not only clearly demonstrates the health system’s neglect of black women’s bodies, but also their exploitation. These flaws within the American healthcare system are serious, and along with receiving a consistently poor prognosis, reason enough for black women to mistrust the institution.

The researchers at Johns Hopkins University never obtained consent for Lacks’s cells, yet claimed complete credit for their unauthorized discovery. The point to stress here is that the cells were never theirs to begin with, yet by endowing Lacks’s cells some humanistic elements—terming them “HeLa”—they manipulated their research to appear as their own. This is similar to what Myriad Genetics is currently doing with its patenting of the BRCA gene.

Three years after Professor Harris’ initial law school presentation we now ask, “What do we do if Myriad wins in the Supreme Court?”

Myriad stole our genes and patented them, so that they can sell us their test. With the news of Jolie’s testing, Myriad’s stock has risen to a three-year high of $34.70 during trading on the NASDAQ market. The trading volume was also much higher, with 2.6 million shares exchanged; more than double the three-month daily average of 1.1 million shares.

There are a myriad of reasons why we should be opposed to Myriad, but the most important is that when it comes to genetic testing, what we don’t know can, and will, kill us. The fight for access to genetic testing is an activist movement that needs to happen sooner rather than later, for all of us.

_______________________________________________________

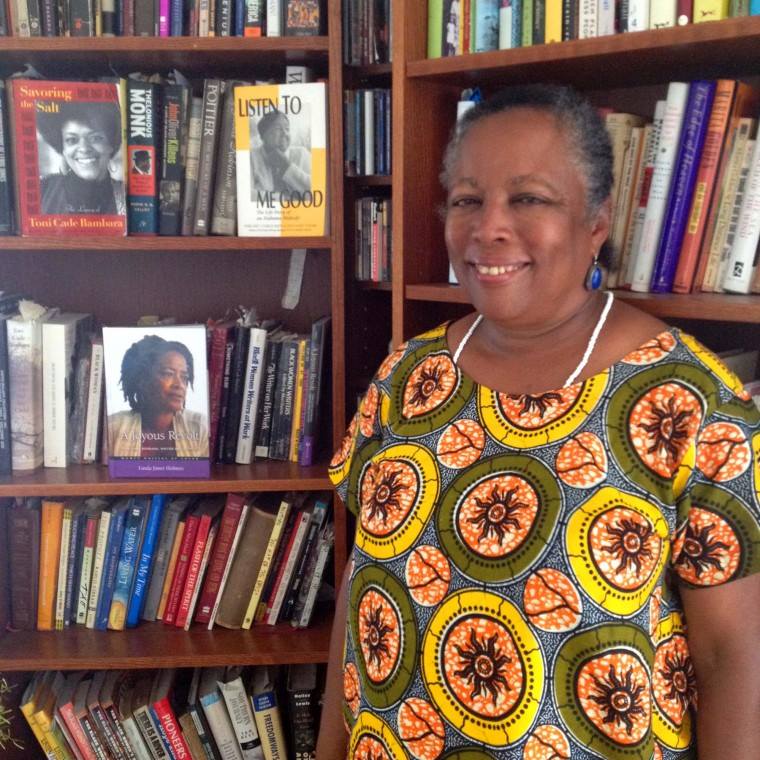

Duchess Harris is Professor of American Studies and Faculty Coordinator of the Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship Program at Macalester College.

Duchess Harris is Professor of American Studies and Faculty Coordinator of the Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship Program at Macalester College.

Christine Ohenewah is a College Junior and Professor Harris’ Mellon mentee. Christine’s summer research plans are to utilize feminist, historical, and theoretical scholarly literatures to focus on how Black women’s invisibilty enables a dichotomy amongst themselves which deters their progression in American society.

Christine Ohenewah is a College Junior and Professor Harris’ Mellon mentee. Christine’s summer research plans are to utilize feminist, historical, and theoretical scholarly literatures to focus on how Black women’s invisibilty enables a dichotomy amongst themselves which deters their progression in American society.

Pingback: Mädchenmannschaft » Blog Archive » Aktionen und Empowerment – kurz verlinkt

Pingback: Mädchenmannschaft » Blog Archive » Aktionen und Empowerment – kurz verlinkt

Pingback: Mädchenmannschaft » Blog Archive » Aktionen und Empowerment – kurz verlinkt

Pingback: Mädchenmannschaft » Blog Archive » Aktionen und Empowerment – kurz verlinkt