Silence Does Not Equal Absence: Lessons from Arizona

By Wendy Cheng

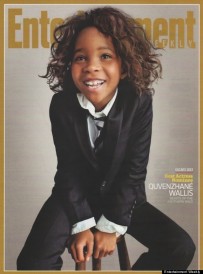

When I heard what writers at The Onion had tweeted about nine-year-old Quvenzhané Wallis during the Oscars, I felt it as a blow to the gut. How could a person think and write such a thing about this beautiful, spirited child? It made me feel – as I often do these days, living much of the time in SB 1070-era Arizona– that there was a hard line that could never be crossed between myself and another type of person: one who could write such hurtful words, or who could read those words and feel that no harm had been done. It was yet another unwelcome reminder that the dehumanizing practices and worldviews of racism and sexism are alive and well.

Yet I, like many of the white feminists whose purported silence has occasioned this forum, remained largely silent on the issue. Granted, I am not white, but I do teach and write about race and social justice. Apart from a few conversations with friends, I read what others wrote about The Onion tweet and reflected on my thoughts and feelings largely alone. I do think that there are moments and situations when we are obligated to act and speak out, and can understand why many people felt that Wallis’s degradation by The Onion was one of them. But I interpret reactions to the treatment of Wallis as an instance in which we cannot assume that silence equals absence and consent. I also believe that if we truly care about being effective in getting other people to change their minds – that is, if we think of ourselves as educators and activists in addition to whatever other roles we may inhabit (e.g. scholars or intellectuals) – we must regard others’ processes of conscientization and politicization with compassion and as much patience as we can muster.

I say this as someone who came late to racial and political consciousness myself – or at least later than those who were born into lives in which they did not have the luxury to ignore the ill effects of social inequalities meted out through group differentiation. I am a second-generation Taiwanese American. My parents benefited from the United States’ recruitment of foreign science and engineering students and professionals during the Cold War, at just the time when they wanted to escape a repressive martial law regime. By the time I finished elementary school, they had made enough money to land us in a predominantly white, upper-middle-class suburb in San Diego. Besides a vague feeling of alienation and difference that I did not recognize for what it was until much later, I never really thought about race or class while I was growing up. I wanted to be an artist and writer and didn’t question that this seemed to mean reading almost exclusively white, male writers and not being overly concerned with social or political issues. In college, I was an English major who also spent a lot of time in the art department. In the classes I took, race, class, gender, and sexuality were barely – if ever – mentioned, much less critically discussed.

After graduating from college, I spent a few years struggling to balance the monotony of temp work with trying to be an artist, and eventually decided to throw in the towel and go back to school. My first semester in graduate school, I took a seminar with the geographer and abolitionist Ruth Wilson Gilmore. The over-enrolled class was filled with advanced students in geography, ethnic studies, and other socially critical disciplines. I understood little of what I read, and even less of what was said – only that all of these people were telling me that the world was very different than what I had believed it to be. I was not convinced. Despite my discomfort, however, my interest had been piqued enough to enroll in a second class with Dr. Gilmore two years later. In that class, suddenly everything made sense. In fact, the world itself began to make sense for the first time. It was as though someone had suddenly turned a light on, and I hadn’t even known that I was sitting in darkness.

After graduating from college, I spent a few years struggling to balance the monotony of temp work with trying to be an artist, and eventually decided to throw in the towel and go back to school. My first semester in graduate school, I took a seminar with the geographer and abolitionist Ruth Wilson Gilmore. The over-enrolled class was filled with advanced students in geography, ethnic studies, and other socially critical disciplines. I understood little of what I read, and even less of what was said – only that all of these people were telling me that the world was very different than what I had believed it to be. I was not convinced. Despite my discomfort, however, my interest had been piqued enough to enroll in a second class with Dr. Gilmore two years later. In that class, suddenly everything made sense. In fact, the world itself began to make sense for the first time. It was as though someone had suddenly turned a light on, and I hadn’t even known that I was sitting in darkness.

Dr. Gilmore – who has been my mentor ever since – had also set an important example for me from that first class forward. She gave me all the necessary ingredients and then let me put them together for myself (though never hesitating to prod when necessary). She never made me feel like I was misguided or on any other “side,” but rather, that she was simply waiting for me to become the scholar and person she knew I could be. It was a proactive practice of patience and belief.

In 2010, I moved to Arizona just months after state legislators passed SB 1070 and a host of other anti-immigrant and racist laws. I had to relearn the subtle but important lesson I had first experienced through Dr. Gilmore, and which I heard echoed in the words of my friend and colleague, the scholar and filmmaker H.L.T. Quan: that silence does not equal absence. She had to say it many times as I was adjusting to living in this state: when I expressed incredulity that “nothing” was being done in Phoenix in response to HB 2281 (Arizona’s anti-ethnic studies law, most of which was upheld by Japanese American federal judge Wallace Tashima just a few weeks ago); when I complained that “no one” seemed to care.

When I stopped assuming their absence, I saw that people were doing extraordinary anti-racist work here in Arizona, both on campus and off: People like Anita Fernández, faculty at Prescott College, who worked with Tucson Unified School District (TUSD) teacher Curtis Acosta earlier this year to arrange for Tucson students to receive college-level credit for courses that were banned by HB 2281. The student activists of UNIDOS, who in 2011 practiced civil disobedience at a TUSD board meeting in order to make their voices heard regarding their own education, and have shown over and over that an ethnic studies education can make people capable and active participants in a democratic society. The staff and workers who run the Arizona Worker Rights Center in Phoenix, educating undocumented workers about their labor rights in the face of tremendous persecution. The activists of the Phoenix chapter of the Black Alliance for Just Immigration (BAJI), who realize that anti-immigrant policies and practices are part of a white supremacist state that all of us must fight, together. A group of mostly young women – some of whom had been educated by the capable faculty of Gender and Women’s studies at the University of Arizona – who this past winter started the powerful blog, MalintZINE, to speak out against the sexism and sexist violence that has fractured the ethnic studies struggle in Tucson.

I also recognized my own imperative to act. At the university level, we have begun to build a statewide network of ethnic studies scholars and educators, and regularly organize events to bring awareness to ethnic studies. Last fall, one of the circles in my personal process of conscientization was closed when my university’s ethnic studies group invited Ruth Wilson Gilmore to speak. In her talk, Dr. Gilmore traced “the birth of ethnic studies” back more than two thousand years before a rapt audience, most of them undergraduates. Two-and-a-half millennia ago, she said, the ancient Greek historian Herodotus presented history as the narration of difference between peoples. This constant and systematic differentiation between “us” and “them” – and its genocidal consequences – became the central epistemological problem of ethnic studies.

In other words, binaries can kill us, whether they are based on race, gender, sexuality, or other identity categories. One of the most canonical insights of women-of-color feminism is Audre Lorde’s statement that “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” We should remember that creating and enforcing binaries is one of the original and most devastating of these tools. We should be fighting for an ever-more-inclusive “we,” rather than making finer and finer divisions between “us” and “them.” As Paulo Freire has put it, “it is possible to convert individuals of the ruling class – but never the ruling class as a class.” Let us be each other’s mentors, as galling as it might be at times; and remember that conscientization is a process. This ever-widening “we” is admittedly aspirational and strategic, but it must be more effective in the long run than continually thinning the ranks of our allies by vigilantly separating out “us” (who really get it) and “them” (who are not sufficiently radical, critical, anti-racist, anti-sexist, and so on).

There is too much work to do for that, in Arizona and everywhere.

____________________________________

Wendy Cheng is Assistant Professor of Asian Pacific American Studies and Justice & Social Inquiry in the School of Social Transformation, at Arizona State University. She is coauthor of A People’s Guide to Los Angeles (University of California Press, 2012), as well as numerous essays and articles.

Wendy Cheng is Assistant Professor of Asian Pacific American Studies and Justice & Social Inquiry in the School of Social Transformation, at Arizona State University. She is coauthor of A People’s Guide to Los Angeles (University of California Press, 2012), as well as numerous essays and articles.

8 Comments