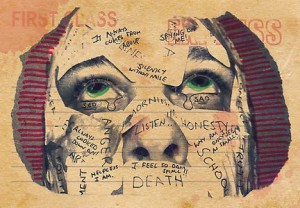

Living with Mentally Ill Parents

By J. Victoria Sanders

Walking with my mom, Maggie, as a kid, I heard someone call her crazy. She wore her black wigs until, with wear, they turned into frayed, layered gray clouds. Her thick nails were caked with layers of chipped maroon nail polish. She stuttered when she spoke, unless she was angry. Her black purse was thick as a mail carrier’s with letters, rosaries, but no wallet. We usually didn’t have money, so missing a wallet was no big deal.

“I am protected by the Lord Jesus Christ, my savior,” she started. And then, all that Cherokee blood that made her cheekbones so high rose to her face. She knew Jesus, yes, but she also knew how to go off. Curses and spittle followed until the accuser backed down.

Maggie had both borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder, triggered by the death of my 12-year-old brother Jose in 1976, but I wouldn’t learn about her diagnosis until I was older. Jose was the youngest of her five children. I was born in 1978, named for Jose and a childhood friend of hers.

Maggie never married my father, Victor. She had been working as a secretary at the time, after a lifetime in Philadelphia via South Carolina. He was a tall, handsome ex-military man who worked in civil engineering. He liked to drink, maybe too much. He had endearing brown eyes that seemed to smile even when he was frowning.

Maggie followed the invisible trajectory of most people who don’t trust therapists, don’t want help and still manage, somehow, to make lives and babies and homes. She unraveled over decades, spinning through communities that believed God alone could cure her. She attended Mass daily before her health declined and it would be hard to prove God hadn’t saved her, since there were no other real reasons that she should have still been alive.

Her mother, Edna, died when she was young. She went to live with an aunt, but she never felt like one of them. She was lighter and quirky, beautiful and thin. She loved chasing men her whole life, even though she once considered becoming a nun.

Whatever issues Victor suffered, he did so in a two-story house in Blackwood, New Jersey. The women in his family called that house “The Basement” because as a little boy growing up in Alabama, he would disappear underneath the house for hours. The reclusive privacy he craved extended into adulthood. He likely had Asperger’s Syndrome, typically marked by severe issues with social situations.

I adored my mother with an all-encompassing love, but I needed to break free of her to create my life. I met my father at my high school graduation and in the years that followed, tried to break into the circle of extreme solitude he’d built around his life with little success. Both my parents were crazy, I argued with therapists, so I must have had what they had. They shook their heads. I had spiritual scars, yes, but I was not them.

Victor didn’t believe in God, but I did, like the woman who raised me.

In the Catholic churches and rectories Maggie frequented for monetary and food assistance, they also offered prayers, if not medication. She once admitted herself to a psychiatric facility, knowing she needed God’s intervention in the form of something stronger than her own willpower.

Victor drank. He kept his distance from the world. That included his children, legitimate and otherwise.

I moved away. I left her in the Bronx to go to boarding school, then college. Maggie’s manic episodes during my youth were scary, unpredictable bursts of anger and rage. They culminated with her choking me and threatening to kill me before I ran away to a friend’s house, my few things in a Hefty garbage bag. Boarding school was my first salvation, writing another, God whenever I believed he was listening and guiding me – a sense that grew over time.

I don’t actually know what Victor believed either because we met so late or because he didn’t know. We never talked about his depression, if he believed he was depressed, or not. I knew from living with him for a few weeks during college, when he stopped speaking to me for days at a time with no warning, that something was amiss. I just couldn’t figure it out.

In my 20s, a few years after college, Maggie’s mental illness was confirmed. When a Philadelphia-based psychiatrist called to get more information about her, I told him our story. “It’s likely that she either has borderline personality disorder or bipolar,” he said. Until that moment, I had believed that whatever was warped about our lives had been connected to my inability to be a better child, to be less of a burden. A chemical imbalance, augmented by a life of abandonment, made more logical sense.

Bipolar disorder creates euphoria and bursts of energy that women artists throughout the ages have used to fuel their work. My favorite author on this topic is Kay Redfield Jamison, an author a colleague of mine recommended I read. An Unquiet Mind and Touched by Fire were the first accessible texts I read about all of the brilliant aspects of the endless manic energy Maggie had at her disposal. The high libido, the endless spending of limited resources, the rage of throwing things and sweating and pacing like a fighter about to haul off and hurt someone were part of the package, too.

The psychiatrist said medication might change her whole interior landscape. What made Maggie better would have also made her bland, zapping her relentless pursuit of happiness. Whenever she tried medication, it made her despondent, sad. She resisted medication for a whole different reason. “It would interfere with my relationship with God,” she said.

God made medication, too, I thought, but I didn’t press the matter. The least I could allow her was the freedom to shape her life however she wanted, after all she had been through: To love her enough, as she was, to pray for her from a distance.

Like a ghost, my father’s spirit hung in the background of my life until I got a call from one of his sisters in 2010. Sometime in April, he hung himself in his New Jersey garage. I was shocked and saddened, the end of any hope of us reconciling dead along with his distant body.

So, when Maggie died on January 6, 2012, I was comforted by the fact that I had warning. About a year before her death, she had been diagnosed with cervical cancer. By the time we discovered she was ill, the cancer had reached its late stages.

By then, I was leaning into my mid-thirties, and learning about her tendency to distance herself from her emotions opened in me a well of compassion, fresh grief for a life of ease she would never know and anger. Almost none of what I experienced growing up with her was about me. It was a bittersweet relief to sit with her, hold her hand and weep.

We cleaned out her house where she collected paper of all kinds — hymnals, prayers, pictures of Jesus with her lipstick stains on them – just like the papers she’d carried around with her when I was younger. She found safety in clinging to these things.

At her joyous memorial service, over 100 people came to send her off to the other side. No one mentioned about her mental state. The same was true about the end of Victor’s life.

Instead, we talked only about the life she led, as best she could without medication, years marked by travel and the endless search for a kind of stillness that always evaded her. She loved to party and loved to dance, her shoulders leading the way for her feet to follow.

I am left, now, to wonder what my parents’ lives would have been like if they had sought treatment for their ills instead of running from them. But forgiveness, someone once said, is giving up all hope for a better past. It is the only reason I will ever endorse hopelessness. My parents would appreciate that they left behind a fighter like me.

_____________________________________________

J. Victoria Sanders has been a journalist, essayist and poet for more than a decade. Her writing has appeared in VIBE Magazine, The Root, Publishers Weekly, the San Francisco Chronicle, the Dallas Morning News, and Bitch Magazine. Her work has been widely anthologized and her publication credits include Secrets and Confidences: The Complicated Truth About Women’s Friendships, Click: When We Knew We Were Feminists, Homelands: Women’s Journeys Across Race, Place and Time and Quiet Storm: Voices of Young Black Poets. Her most recent essay, about Madonna’s connection to black folks, will appear in the forthcoming Soft Skull Press anthology, Madonna and Me. She lives with her adorable dog Cleo in Austin, TX, teaches journalism at the University of Texas and satisfies her love for inspirational quotes and random beautiful things at www.jvictoriasanders.com. She can be reached on Twitter: @jvic or by email at joshunda@gmail.com. She currently blogs at http://thesingleladies.wordpress.com/

J. Victoria Sanders has been a journalist, essayist and poet for more than a decade. Her writing has appeared in VIBE Magazine, The Root, Publishers Weekly, the San Francisco Chronicle, the Dallas Morning News, and Bitch Magazine. Her work has been widely anthologized and her publication credits include Secrets and Confidences: The Complicated Truth About Women’s Friendships, Click: When We Knew We Were Feminists, Homelands: Women’s Journeys Across Race, Place and Time and Quiet Storm: Voices of Young Black Poets. Her most recent essay, about Madonna’s connection to black folks, will appear in the forthcoming Soft Skull Press anthology, Madonna and Me. She lives with her adorable dog Cleo in Austin, TX, teaches journalism at the University of Texas and satisfies her love for inspirational quotes and random beautiful things at www.jvictoriasanders.com. She can be reached on Twitter: @jvic or by email at joshunda@gmail.com. She currently blogs at http://thesingleladies.wordpress.com/

44 Comments