Toni’s Powerful Intervention: Artist Tom Feelings Talks with His Son

By Kamili and Tom Feelings

Editors’ Note: Kamili Feelings conducted this previously unpublished interview in 2002 with his father, the award-winning artist Tom Feelings, prior to his father’s death on August 25, 2003. We are very grateful to Linda Janet Holmes for being our Bambara bridge to Kamili Feelings. We are also deeply grateful to Kamili for immediately saying, “Yes!” to our request to share this interview with The Feminist Wire’s readers.

Throughout this interview, I use the term “intervention.” Here, I use the word “intervention” to refer to the act of speaking and/or acting out in order to raise someone’s consciousness or political awareness. For instance, a child might suggest to her otherwise progressive parent to look critically at how she uses murderous language to refer to LGBTQ people. Or a grandmother might be corrected by her otherwise-respectful daughters because of derogatory comments she makes about people darker than herself. Or a friend offers me her unsolicited perspective over the degree of misogyny found in my own words. These are interventions. These are challenges to take a look at yourself.

As members of “progressive” communities, these kinds of interventions can be embarrassing. We flatter ourselves into thinking that “we’re all right” and it’s always the other person who has the problem. But Toni Cade Bambara, once wrote that revolution starts “with the self in the self.” For that reason, I was not surprised to learn in a conversation with my father that these two very conscious Black artists who actively struggled through that personal revolution continue to speak to each other even now, several years after Toni’s passing.

Toni intensely supported my father’s groundbreaking work, The Middle Passage: White Ships Black Cargo. She sent my Dad warm words of congratulation in letters that mentioned she consistently “burned a candle” in spiritual support of a project that took years to finish. When the book was finally published, Toni wrote my father a letter in which she hailed the completion of the work. While Toni was still alive, however, my father learned from mutual friends that Toni wasn’t quite satisfied with the work. Since the writer and filmmaker often considered her life to be intentionally lived “out loud,” it is not surprising that she may have wanted the concerns she expressed “out loud” to others to be constructively relayed to the author. My father was never able to get confirmation of Toni’s criticism, because she passed shortly after his book was published. They never talked about the work, which my father greatly laments.

Toni intensely supported my father’s groundbreaking work, The Middle Passage: White Ships Black Cargo. She sent my Dad warm words of congratulation in letters that mentioned she consistently “burned a candle” in spiritual support of a project that took years to finish. When the book was finally published, Toni wrote my father a letter in which she hailed the completion of the work. While Toni was still alive, however, my father learned from mutual friends that Toni wasn’t quite satisfied with the work. Since the writer and filmmaker often considered her life to be intentionally lived “out loud,” it is not surprising that she may have wanted the concerns she expressed “out loud” to others to be constructively relayed to the author. My father was never able to get confirmation of Toni’s criticism, because she passed shortly after his book was published. They never talked about the work, which my father greatly laments.

My father has great respect for Toni’s insights coupled with her purposeful and significant history of intervention and being outspoken. Like many others, my father respected Toni as a truth-teller.

One of Toni’s essays published in Deep Sightings and Rescue Missions also provided confirmation for him that what he heard about Toni’s comments were true, because the criticisms he heard mirrored themes explored in the essay he read after Toni passed.

This interview revolves around how Toni’s politics, writing, and her conversations with their mutual friends, as well as her letters and postcards to him convinced my father that Toni made his work the subject of an intervention. To some, this interview may be peculiar or even quirky. For my father, Toni’s intervention continues to be a significant life-time lesson.

Kamili Feelings (KF): How does the term “intervention,” as I’m describing it, fit here?

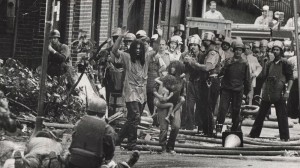

Tom Feelings (TF): I’ve told you that I respect Toni for what she’s tried to “tackle” in her lifetime. She dealt with the most difficult things—our experiences that were happening right then and there because she knew it was all rooted in our collective past. So the “MOVE” story in Philly…the Atlanta Child Murders, Toni was there. You’ve told me yourself in the interview in Artist and Influence that she said she became physically sick going into and during the whole sordid mess of investigating the Atlanta Child Murders. It must have been trying taking on all that pain—the suffering of the children, the suffering of the families of the children, the suffering in the neighborhood, and trying to reckon even with your own degree of suffering for all of them. That’s potentially fatal even within the realm of the imagination. It’s been what I’ve been trying to do throughout the whole experience of The Middle Passage.

As far as “interventions” go, I can only guess at what she might have disapproved of in my work now, but the finding out, the delving into the idea that self-interrogation is where we need to begin is my interest now. A constant purging of the self for what’s useful and what is not is key to developing revolutionary consciousness. Let me make this clear: It’s because I respect Toni and the revolutionary work that she made happen in her lifetime that I pay extra special attention to any criticism she might have shared about my images. Because I know where Toni’s coming from in regard to her commitment to Black people is the reason why I value her criticism of my work. It makes for a very great kind of communication between artists: one who has passed on and one still living.

KF: I’ll flat out ask what some folks are bound to ask upon reading the first few lines of the interview describing what we’re doing: Why is this significant for those who want to remember the life of Toni Cade Bambara?

TF: Well, Toni Cade was always interested in that “revolution within the self,” the idea that self-interrogation is where we all need to begin. A constant purging of the self for what’s useful and what’s not is a part of that revolutionizing spirit. Let me make this clear. It’s because I respect Toni and the revolutionary work that she’s made happen in her lifetime that I pay extra special attention to any criticism she might have shared about my images, because I know where Toni’s coming from in regard to her commitment to Black people. That is why I value her criticism of my work and what she might have wanted me to know. I want my vision to improve as a result of anything she might be able to impart even now.

There are many ways of communicating that go beyond just physically talking to someone who’s now passed. If Toni’s coming to me and talking to me through her posthumous work, I accept that whole heartedly. I don’t try to rationalize it. This kind of spiritual investigation of the self through our deceased loved ones seems in perfect keeping with the idea of that intervening. And maybe, after all, it’s some sort of call to artists to move towards a greater accountability to one another in terms of our sharing in regard to being open to criticism. And really, I think that she’d be pleased knowing that our friends valued her life work enough to share her critical words with another artist.

KF: Yes, Toni’s comment could easily have not been passed on just out of consideration for your feelings.

TF: What runs through my mind in terms of trying to tell the kinds of stories that Toni tells is the poet Rilke’s advice: “Hold to the difficult, don’t choose the easy way…” And this is what she consistently did. In her life and in some of her work that I’ve already mentioned, she celebrated the joy, but she also chose to try to do justice to the complicated, the complex, and the painfully convoluted. She tackled stuff in the truest sense of that football term. But she tried to sing the bittersweet song of that experience. I respect that, because I know from working on The Middle Passage what a dangerous edge that is to walk on. But she did as a writer, activist, filmmaker. And continues even now obviously past just her physical death…

KF: Now having heard through the grapevine about her consideration of the book, what do you gain from that knowledge generally? What lessons do you pick up from this exchange for future reference as far as artists speaking to one another, sharing?

TF: Listen. My loft was open to all kinds of people who came through, buying posters or just looking at the work. But I showed them all the dummy of The Middle Passage, and they all commented in one way or another.

But I see now that respecting Toni’s work so much, I should have actively sought out Toni’s criticism of my book. Toni could have specifically helped me take it to another level, because she was always actively working within much of that complexity. Just by pointing out some things that I couldn’t see. Lucille Clifton and her husband offered the same kind of what you are now calling an intervention for me years ago in a published New York Times Book Review about an earlier work of mine, Black Pilgrimage. And that changed the course of my thinking.

But I see now that respecting Toni’s work so much, I should have actively sought out Toni’s criticism of my book. Toni could have specifically helped me take it to another level, because she was always actively working within much of that complexity. Just by pointing out some things that I couldn’t see. Lucille Clifton and her husband offered the same kind of what you are now calling an intervention for me years ago in a published New York Times Book Review about an earlier work of mine, Black Pilgrimage. And that changed the course of my thinking.

Now, of course, other artists came in and talked to me about the subject too. But Toni was working on and delving deeply into the stark realism of our present conditions, which is all connected to the past. Given our commitments to visual aesthetics, our paths were probably nearing, but we never had the chance to even sit down and talk about that. I believe my living in Africa gave me a sense of my own importance with respect to the power of the image to reach into the psyche of the people and provide an instrument for healing. From her writing, it’s clear that she believed that too. I think she knew how vital it was that we all “get it right” in regard to putting out healing images. She would have said things to me straight—knowing I could “take it,” knowing I really wanted to tell this painful story in my best way…letting it come through me in the best way. That all helps when some of the baggage I‘ve picked up over the years can be learned away with the truth. So it’s vital—urgent even—that artists talk to one another, even now as Toni is doing in this indirect way.

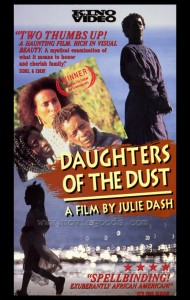

KF: In fact, the last letter Toni sent to you—encouraging you in your travails with the book—was mostly celebrating the success of Julie Dash‘s film, Daughters of the Dust, suggesting that you must see it. This film ended up being the subject of the article you were reading, “Reading the Signs, Empowering the Eye” when you landed on why you think Toni might have been critical of your work.

TF: Yes. I believe that Toni ended up talking to me even after her death through my investigation of her words. I believe she was reaching out to me because she saw some earnestness on my part in regard to getting it right. It’s healing to know that we’re still talking—that we didn’t quite miss our opportunity to rap.

KF: Let’s talk briefly about what Lucille and Fred Clifton’s criticism was of your earlier book, Black Pilgrimage, because as you started to say, this criticism directly touches on what Toni Cade Bambara’s words had the power to do: make you look twice at yourself and your work.

TF: The criticism basically stemmed from some comments I made in the book about Black American culture. I believed at the time that we couldn’t really classify our living and surviving within this system as culture. I thought of it as mere surviving, staying afloat, and didn’t really value it in the way that I value the culture of a “free” people, namely Africans. Fred and Lucille Clifton came and flat-out told me, within the context of the article, that that was a “white-dominated idea of culture,” and I needed to rethink it.

KF: Do you rethink it now?

TF: Of course. I was not really considering the value of resistance struggle that Toni always calls upon in her work. Now I may have seen these things as part of resistance movements, but I didn’t value them as real cultural aspects of a people. It was Lucille and Fred who initially made me conscious that I was thinking within a “white-dominated” frame of reference. And I needed to be vigilant within that rethinking they were calling upon me to do.

KF: How does that play out for you in regard to what you think Toni Cade Bambara disapproved of in your work?

TF: Toni got my attention with the one statement she made in “Reading the Signs, Empowering the Eye” about male narratives of resistance being limited. They are always “numbered,” she wrote, “leader-led” and “sweeping in process and effect.”

KF: In other words, resistance or rebellion all happens by plan and order, and it all happens in one epic very masculine moment. Take-over! Revolt! Like a Mel Gibson movie: Braveheart. But do you think that this kind of representation also occurred in your work?

TF: Yes. And in some ways, I never thought of it like that before. Not only are no women featured “fighting back” in the pictorials, but they are solely acted upon and molested within the picture narrative. I realize now that that was limiting the possibilities within our actively resisting oppression.

KF: What other ways might Black people involve themselves in resistance aboard slave ships then?

TF: Toni, in praising the use of the character Yella Mary in Daughters of the Dust, references the way Black women had a lot of ways of resisting oppression besides through physical confrontations, which I failed to take account of before now. Toni talks about how black female prostitutes and domestic workers, for example, were all in a position to resist from their particular vantage points. “Any ordinary day” offers us the opportunity to resist oppression, Toni wrote. From off of Toni’s cue, I’m now able to see how I needed to carry the Cliftons’ criticism even further into my illustrated work to show those aspects of survival culture among our people, male and female, even aboard the slave ships.

I do this now by featuring the suicide that went on among us; it’s as active of a way of resisting as fighting is. But mercy-killings were yet another way. Self-mutilation is another serious act of denying the white man what he thinks is his “rightful price” for you. And infanticide, as Toni Morrison illustrates in her novel (Beloved), is yet another way of denying oppressors the satisfaction of claiming my/your/all of our bodies, which of course often means facing serious repercussions. Yet these actions are all seen by western society as singularly ugly way of reacting to oppression. They’re not classically heroic in the resistance sense—what you referred to as the “Mel Gibson-Braveheart” sense.

I do this now by featuring the suicide that went on among us; it’s as active of a way of resisting as fighting is. But mercy-killings were yet another way. Self-mutilation is another serious act of denying the white man what he thinks is his “rightful price” for you. And infanticide, as Toni Morrison illustrates in her novel (Beloved), is yet another way of denying oppressors the satisfaction of claiming my/your/all of our bodies, which of course often means facing serious repercussions. Yet these actions are all seen by western society as singularly ugly way of reacting to oppression. They’re not classically heroic in the resistance sense—what you referred to as the “Mel Gibson-Braveheart” sense.

It’s ironic that the Cliftons hipped me to something thirty years ago that ended up taking shape in a most meaningful way for me now in my interpretation of Toni’s words.

KF: How so?

TF: I myself thought at one time of this kind of resisting as being ugly and compromised aspects of our cultural baggage. But these were again white-dominated ideas of culture and resistance. I’m starting to recognize how while these acts may weigh a heavy physical price on our individual lives, they may be spiritually redemptive for the soul. These ugly even outrageous acts reclaim our peoplehood from people robbers. This makes me conscious that I need to keep rethinking how that ought to take shape visually in a picture book.

KF: Let me be clear.You’re saying that you took the Clifton’s critical words to heart, but didn’t quite put them to work fully in your illustrations?

TF: Maybe. Toni’s words are making the Cliftons’ critical remarks clear to me now more than ever before. I think on board that slave ship in the face-off between Blacks and Whites, I did not include any Black women, not even in the close-up of the faces. The inclusion of Black women in such a face-off would have been a tremendous image for us all to feed off of. Clearly, I was not vigilant enough in rethinking my work.

KF: Yet, you mentioned just now privileging the spirit world over the material one. Isn’t this spirit world that you mention the very realm from which Bambara’s criticism is getting to you now? You seem to be gaining much more from her spiritual presence because her work inhabits your thoughts so powerfully now.

TF: Since we never were able to sit down and talk about this stuff, yes. So in some ways, through the mouths of her friends and through her writing and more directly through this interview, Toni’s performing that intervention that we weren’t able to negotiate face-to-face.

KF: How will this play out in your future work?

TF: The next book I’m illustrating is about our landing here in the southern parts of the United States and what happened afterwards. But this future work has to include pictorials of women actively resisting oppression in much more complex ways. I’m imagining it as a more complicated and complex response to what I’ve been thinking about now via Toni.

KF: How will this play out in terms of it being controversial?

TF: The atmosphere for criticism of any Black artist who is obviously trying to do something valuable for Black people is always going to be charged. In my case, people still look at me like I’m crazy when I do some serious rethinking because of another person’s criticism of my work. It might help that I’m the one seen as initiating this self-interrogation through Toni’s work. But since this is that quirky kind of article anyway, I want to make sure folks understand the deeper reasons for even putting this out there. I value Toni’s work in the world and it is her work that makes me rethink myself in regard to my own work.

Besides, in fairness, there are so many motivations from the outside world for critiquing black artists negatively that, yes, we shy away from even the suggestion of negativity because we don’t want to be tied into one more kind of attack from the establishment. We are all maybe redefining the concepts of criticism everyday so that it has some real healing value in our lives.

KF: Are you suggesting that we need to wrestle the term “negative criticism” away from the usual good/bad context?

TF: Not just the words themselves, but the whole feeling it gives you: that it’s wrong; that it’s causing trouble; that it’s stirring up something best left alone; that it can’t help you or anyone else one bit. Toni’s comments about her difficulties with the book were apparently made within a circle of women friends that she and I both shared. Yet, even the fact that I heard about what she said might be seen by some (not by Toni or our friends, I’m sure) as breaking some kind of trust. We sometimes don’t even practice criticizing in our private lives, because we think it’s going to create static in the relationship, and sometimes, it does!

KF: But then how do we grow? Maybe folks need to keep pushing for that concept of forthrightness, in print at least, that you’ve described to me was a prevalent attitude back in the sixties and seventies.

TF: Right. The kind of forum that was fostered by magazines like the Liberator (where I first picked up on Toni’s work) and Freedomways, where people loved you by telling the absolute truth and not sparing feeling because what was going on around us was so much more important than us licking wounds. There’s too much patronizing in that. It’s painful, but if I’m part-wrong, please work at telling me like Toni ended up doing in her way so that I can get it all right. Please. It’s not about saving face.

KF: But you encourage that.

TF: Yes. ou might have to justify why I’m wrong and lead me down the road to seeing it. But, yes I encourage that kind of criticism of all of my work. And I think most artists do, too. The important thing, for this artist at least, is always how and what do I do with the criticism after it comes down? It doesn’t matter how it comes down—handed down by man, woman, word-of-mouth, however. What matters is how do make use of it. Hearing and verbally/consciously accepting the criticism is the beginning, but then how do you bring the criticism into the work—transforming it, especially within the realm I operate which is visually?

KF: And how do we actually do that when criticizing the visual artist without telling you how to draw?

TF: At this point, I’ve been open to any and all suggestions about my work. I can take it from there. Be as imaginative as I can. We’re doing just that right now with Toni’s words, I think.

KF: Let’s be real and ask how does another artist’s temperament, personality, lifestyle, reputation affect your ability to take in his/her perspective on something as personal as your work?

TF: I like to think that I think about every comment that’s made about my work. But when you’re dealing in similar fields of interest with similarly fierce kinds of commitment to revolutionary work as with Toni and me, the ear has to be open a little wider because otherwise you just may miss something very important to your own development as an artist.

Then again, somebody comes off the street one day and absolutely shifts my gears in terms of how I conceived of art being created. One quick story to illustrate: I used to think I had to suffer in order to work on a book on suffering. One of these women who was into health foods came around my loft and pointed to my gut one day, ignoring my whatever theory about the artist suffering for his art and told me in no uncertain terms that my potbelly was just backed-up shit. Well, the visual image knocked me out, but it also got me to thinking about I how I as an artist needed to be around to finish this book. I became much more health conscious from then on. The book got finished, and I’m around to talk about it maybe thanks to her words—this woman’s intervention.

KF: In harmony with the Toni project, it seems that many women have taken unsolicited steps to encourage you in your development as an artist or have intervened one way or another.

TF: In keeping with the spiritual tone of this interview, yes. I remember when I was weary of working on The Middle Passage, and I would go and lie down. My late grandmother would come to me and say, “Get up and work. You’re not doing this for yourself.” That’s very much in keeping with how Toni’s been coming to me within the Bambara project that we are in the midst of now.

KF: Well, to further validate some of what we’re talking about here. Bambara has this nice story in Deep Sightings about her talks with a “grandmother” of her own in the form of a neighbor of hers. As a young girl, she came to the woman’s apartment bursting at the seams, content to hog some bit of knowledge that she’d gained about the world to herself and for herself only. But the woman chastised her for it. “If your friends don’t know it, then you don’t know it, and if you don’t know that, then you don’t know nothing.” She describes this neighbor in retrospect as teaching her the true significance of “critical theory,” and that was about sharing her knowledge out loud, and not hoarding it. “If your friends don’t know…then you don’t know nothing.” Maybe Miss Dorothy was telling Bambara to share it all, to share your knowledge no matter how.

KF: Well, to further validate some of what we’re talking about here. Bambara has this nice story in Deep Sightings about her talks with a “grandmother” of her own in the form of a neighbor of hers. As a young girl, she came to the woman’s apartment bursting at the seams, content to hog some bit of knowledge that she’d gained about the world to herself and for herself only. But the woman chastised her for it. “If your friends don’t know it, then you don’t know it, and if you don’t know that, then you don’t know nothing.” She describes this neighbor in retrospect as teaching her the true significance of “critical theory,” and that was about sharing her knowledge out loud, and not hoarding it. “If your friends don’t know…then you don’t know nothing.” Maybe Miss Dorothy was telling Bambara to share it all, to share your knowledge no matter how.

TF: As we talked about before, maybe this conversation ought to be piggy-backed onto a larger call for accountability by artists talking with one another about their work in regard to say gender parity, for example.

KF: Some people will say that it doesn’t matter what’s been overheard about what Toni said about your work or even what she is saying to you now. The question is, will your work stand the test of time? Developed over a period of twenty-some odd years, the work is powerful. How do you jibe those words with what you genuinely feel now Toni was/is pushing for in regard to your work? How do you meld the two criticisms together, if at all?

TF: I don’t think these are two different criticisms at all. Like many socially conscious people, I think Toni both cherished The Middle Passage and wanted to push further into the future within the work. And, I do too. Like the folks you just mentioned who might not understand the reasoning behind this interview, I believe whatever criticism Toni had of my work comes from the exact same loving place that other people’s wholehearted embrace of the work does. But however the love comes, I do and have to keep vigilant. I must keep reminding myself, as the Cliftons once told me to do, to keep challenging that western-dominated idea of culture and of struggle. To go further all the time, I have I have to do more than simply reject notions that I know are wrong. But I have to keep coming up with something that is an essentially human and useable response to our oppression. To use Toni’s words, it’s an “emotional struggle” against forces from without and from within. It makes me very conscious of how much more I’ll have to struggle not to lose my sense of the potential role of the artist in revolutionary struggle. Like Toni always said, we’ve got to make “revolution irresistible” everywhere and in everyone.

KF: And what do you think Toni is saying right now?

TF: Oh, I think that she’s getting a kick out of the fact that here we are (two men—a father and one of his sons) using her words as a jumpstart to critical evaluation of ourselves and whatever our collective work in the world will be. It immediately brings to mind James Baldwin’s words:

The role of the artist is exactly the same as the role of the lover; if I love you, I have to make you conscious of the things you don’t see.

She’s probably tickled a deeper hue of black right now as we speak.

Kamili Feelings is a recent graduate of the pedagogical program at The London International School of Performing Arts. He has taught extensively about theater, writing, his father’s work, and his own work since 2002. He is an alumnus of the Brown University playwriting program, where he studied with such theater luminaries as Paula Vogel, Nilo Cruz, and Aishah Rahman. Since that time, he has focused on funny, personal, autobiographical projects involving his research travels to Mexico and Ghana, West Africa over the decade.

“When I am asked what kind of work I do, my answer is that I am a storyteller, in picture form, who tries to reflect and interpret the lives and experiences of the people that gave me life. When I am asked who I am, I say, I am an African who was born in America. Both answers connect me specifically with my past and present…therefore I bring to my art a quality which is rooted in the culture of Africa…and expanded by the experience of being in America. I use the vehicle of ‘fine art’ and ‘illustration’ as a viable expression of form, yet striving always to do this from an African perspective, an African world view, and above all to tell the African story…this is my content. The struggle to create artwork as well as to live creatively under any conditions and survive (like my ancestors), embodies my particular heritage in America.”

—Tom Feelings

Pingback: Feminists We Love: Linda Janet Holmes [VIDEO] - The Feminist Wire | The Feminist Wire