Lessons on What It Must Be, Not What It Could: Growing Up Black and Boy in America

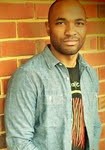

By Guest Contributor on March 14, 2013By Hashim Pipkin

At age twelve, before I had one full year of formal schooling, I had a notion as to what life meant that no education could ever alter, a conviction that the meaning of living came only when one was struggling to wring a meaning out of meaningless suffering. Richard Wright, Black Boy

One must say yes to life, and embrace it wherever it is found and it is found in terrible places. Generations do not cease to be born, and we are responsible to them because we are the only witnesses they have. The sea rises, the light fails, lovers cling to each other and children cling to us. The moment we cease to hold each other, the moment we break faith with one another, the sea engulfs us and the light goes out.” James Baldwin, “Nothing Personal, The Fire Next Time

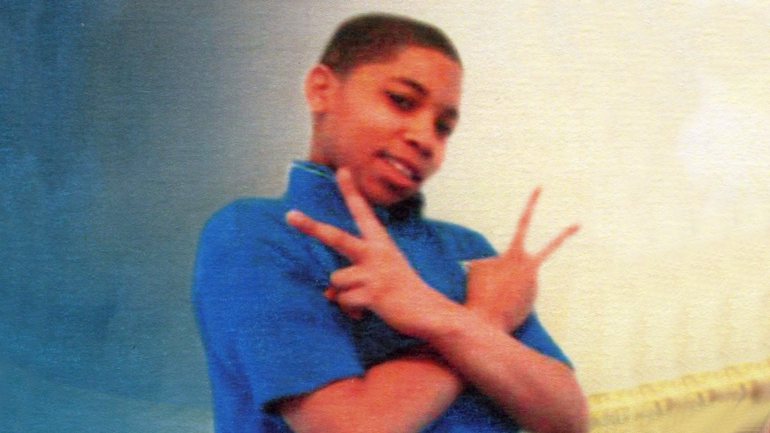

There is a very peculiar American cultural tradition that is inappropriately obsessed with “evaluating” black men. The residue of chatter about what Trayvon Martin did to earn his death or what President Obama has yet to do to earn the respect of citizens within this country is smeared thin, but proliferated wide in this country’s political and social imaginary. Aside from the ridiculousness of this American instinct to assess black men, it fails also in its refusal to consider that each one of these black men was once a black boy. And growing up black and boy in America just so happens to be one of the most dangerous and lonely pursuits issued by this country.

There is a very peculiar American cultural tradition that is inappropriately obsessed with “evaluating” black men. The residue of chatter about what Trayvon Martin did to earn his death or what President Obama has yet to do to earn the respect of citizens within this country is smeared thin, but proliferated wide in this country’s political and social imaginary. Aside from the ridiculousness of this American instinct to assess black men, it fails also in its refusal to consider that each one of these black men was once a black boy. And growing up black and boy in America just so happens to be one of the most dangerous and lonely pursuits issued by this country.

It is important to look back. Much is always found there because much has been left there. However, looking back continues to be one of the biggest crimes this nation commits daily on the black men who live under the heat of her gaze – a gaze that has animated, through its hegemonic practices, this country’s popular culture. American “cool,” which drives our country’s media engine is fueled at the expense of black men and boys’ inaccessibility to the good, American life. Our perceived militancy, our improvisations in fashion, our jargon – all of it – is a reaction to that disenfranchisement. Whispers of this country’s transactions with the bodies and cultural contributions of black boys and men are getting louder, but not clearer. And the noise that is created in that unknowing is silencing most oppressively the dreams of those caught in the middle — America’s black boys.

The interior lives of American black boys go unnoticed purposely. And by interior I mean the story underneath the sagging pants phenomenon and the cold media coverage of the mass shootings in Chicago -– the hidden narrative that instead considers the bend of moonlight that touched a black boy’s bed as he uttered his desperate prayer at night for the bullying at school to end because he is attracted to the other boys in his class or the story that gives voice to the helpless gloss that remained in his eyes hours after the job interview because of his failed attempt at tying his tie since there was no father to teach him how or the story that does not mock the seemingly eternal rush of cold sweat that drips from his forehead to his chest seconds after sex where he and his partner’s regret for not using a condom fills the room.

The absence of these stories in American popular culture have falsely persuaded too many in what black boys are “capable” of achieving or worse than that – what we can handle. This is the fundamental dilemma when figuring out how to raise a black boy. There is an ethic to give us “just enough” to get us to “just where we need to be.” Every move is capped off at the baseline: he just needs to graduate or he just needs to find a job. Dreaming of more is a lesson that we aren’t gifted because America’s culture of fear and surveillance has convinced those involved in the lives of black boys that dreaming of more might get in the way of the untested certainty of having to “save our sons.” The problem here is that anticipating a black boy’s need for intervention never allows the space for prevention that makes intervention unnecessary. And this is the goal, right?

A daytime talk show dedicating an episode to black teenage fathers who need to “step up” or a t-shirt with a stock image of a black boy’s face next to Obama’s are not true attempts at offering black boys the choice to dream and live into the possibility of those dreams over the realities that many black boys face in this country. We deserve that.

Imagine what inheriting this legacy of fear and neglect means for our growing up. What should we do year after year when the channel that is supposedly concerned about those who look like us makes explicit that “black girls rock,” (and they do), but offers silence in response to the logical question that follows: do black boys rock, too? The silence in these moments of choosing to celebrate and nurture the potential for and attainment of excellence by black boys is no longer just silence – something is in fact stated and that is: your ability to grow as the best black boy and black man you can be is not considered here. So, black boys are left to make due only with what reality signifies to them as real. That’s the lesson most, if not all, black boys are taught growing up in America.

Imagine what inheriting this legacy of fear and neglect means for our growing up. What should we do year after year when the channel that is supposedly concerned about those who look like us makes explicit that “black girls rock,” (and they do), but offers silence in response to the logical question that follows: do black boys rock, too? The silence in these moments of choosing to celebrate and nurture the potential for and attainment of excellence by black boys is no longer just silence – something is in fact stated and that is: your ability to grow as the best black boy and black man you can be is not considered here. So, black boys are left to make due only with what reality signifies to them as real. That’s the lesson most, if not all, black boys are taught growing up in America.

I was nine and wanted a journal for Christmas. I was instead given a video game for the family PlayStation. That was my first lesson in how my black boy“ness” would be received in this country. I wanted to write. I wanted to sit next to language and see how close it could get me to the dreams I entrusted to those sheets of paper, but I was instead given the opportunity to sit in front of a screen and move a joystick. Yes, this was about gender performativity and a kid not getting what he wanted for Christmas. But it was more about choosing not to gather around the potential for hope to generate and the abandonment of protection for my human possibility only because of the particularities that formed inside of me – that I was black and that I was a boy.

These lessons are no longer acceptable for me. As a former black boy trying to make sense of the same world that placed my most radical dreams for self in a locked glass box of which I was forced to view, but not given the key to unlock, I now find myself resisting that lie and fiercely rebelling against it. I now seek to shatter that glass box. From each of those pieces of hardened sand, I seek to create the art I am told I am not yet able to speak and this country is not yet ready to hear.

There is no question that I am witness to that notion, that conviction, that acceptance of hopelessness Wright speaks of in the quote that introduces this essay. However, like Baldwin challenges me to do in the quote beneath Wright’s, I am persuaded out of the sheer survival for greatness for each unborn black son to imagine what life could be. I am willing to inject hope into that terrible place. Black people are masters at that alchemic practice. We’ve had to be. Black boys and black boys who become black men are no different. Trust me.

_________________________________

Hashim Pipkin is a writer, teacher and culture critic. He is interested in black sexual politics, black social ethics and the application of Marxist and queer theory on American popular and material culture. He is a former public school teacher, educational administrator and National Endowment for the Humanities Scholar. He is an honors graduate of Georgetown University and also the recipient of the Robert W. Woodruff Fellowship at Emory University. He is at work on his first collection of essays, Surely Free: Black People and Love.

Hashim Pipkin is a writer, teacher and culture critic. He is interested in black sexual politics, black social ethics and the application of Marxist and queer theory on American popular and material culture. He is a former public school teacher, educational administrator and National Endowment for the Humanities Scholar. He is an honors graduate of Georgetown University and also the recipient of the Robert W. Woodruff Fellowship at Emory University. He is at work on his first collection of essays, Surely Free: Black People and Love.

All Content ©2016 The Feminist Wire All Rights Reserved

12 Comments