how time passes now, how space changes here: Black Feminist Calculus and A Review of R. Erica Doyle’s Proxy

Months ago, I was sitting in a Laotian restaurant talking about the possibility of Black Feminist Calculus with the brilliant mathematician and carpenter Maia Boudreaux and she said:

Months ago, I was sitting in a Laotian restaurant talking about the possibility of Black Feminist Calculus with the brilliant mathematician and carpenter Maia Boudreaux and she said:

I appreciate Maia (for imagining that I might be able to catch the keys and) for blowing my mind. I have been walking around ever since thinking “Calculus is happening now. Wow! Calculus is happening right now!” Dear reader, calculus is indeed happening right now as I type this. Right now as you read this. It is indeed a Black feminist miracle to understand the complicated math that is happening in my breathing, moving, dancing body in relationship with a society that struggles to figure me out. Or as June Jordan said in a tribute letter to Audre Lorde after Lorde’s death:

“We knew better. We had been Black children. And each of us had given birth to a black child here, in America. So we knew the precious unimaginably deep music and the precious unimaginably complicated mathematics that our forbidden Black bodies enveloped.”

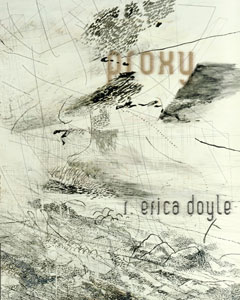

June and Maia are on to something. So I was geeked (but not completely surprised) when I opened Cave Canem Fellow, Astraea Lesbian Writers Fund Awardee, Tongues Afire Writing Workshop for queer women and trans and gender non-conforming people of color-founder aka warrior poet R. Erica Doyle’s new book of poems Proxy and saw….calculus.

June and Maia are on to something. So I was geeked (but not completely surprised) when I opened Cave Canem Fellow, Astraea Lesbian Writers Fund Awardee, Tongues Afire Writing Workshop for queer women and trans and gender non-conforming people of color-founder aka warrior poet R. Erica Doyle’s new book of poems Proxy and saw….calculus.

First of all, how much calculus does it take for R. Erica Doyle to exist as all the artists that she is? Meditate on that and watch the curves, limits and transitions graph the outlandish in your mind.

If that wasn’t enough for me to draw the connection I already wanted to draw with Black Feminist Calculus, Doyle’s text works closely with David Berlinski’s A Tour of the Calculus, a critically acclaimed book designed to describe the relationship between calculus and the workings of the everyday universe. The book as a whole and each section begins with an epigraph from Berlinski’s text.

If that wasn’t enough for me to draw the connection I already wanted to draw with Black Feminist Calculus, Doyle’s text works closely with David Berlinski’s A Tour of the Calculus, a critically acclaimed book designed to describe the relationship between calculus and the workings of the everyday universe. The book as a whole and each section begins with an epigraph from Berlinski’s text.

This book of poems is more than an application of theoretical calculus to the embodied experiences of queerness, daughtering, patienthood, smoking, sexuality, heartbreak, and cystic bleeding reproductive organs, but it is that. Doyle introduces us to a character coming to a number of limits, mathematical, existential, biological and social. Actually, while allowing us to journey through the entire book through one persona, somewhat like Dionne Brand’s most recent works Inventory and Ossuaries, Doyle tells us that we ARE that character confronting all these extremities in the Cartesian plane, using the second person throughout the text (like if Junot Diaz’s short stories could be poems and queerer and better).

I wonder what sort of space, what sort of projected life the obscured speaker conferring you-ness onto the reader affords themselves. Is it a multiple speaker? A chorus speaking to you about you as only you would know what you are experiencing? Is the narrator the proxy, that ally who can be trusted to speak on our behalf? In this case, I think Doyle’s choice to use the second person is a way of writing on us, writing on the readers, a process that the character herself imagines engaging with the bodies of her sexual partners and lovers. Describing a series of lovers as different types of books, the narrator tells “you” that the lingering lover becomes more of a private product: a letter. “She is a letter in the envelope of your body,” the narrator proposes.(48) And what implications do our bodies as envelopes have on our responsibility to each other. To protect? To deliver? What are the words we cannot see inside ourselves from the presence of the beloved other. How do we hold each other so completely that we cannot know what it is that we have. To say.

To say that Doyle’s project is about the calculus of the queer, desiring, dying, deviating defying body is to oversimplify (even though that project would not be simple at all). Proxy also pushes back against the idea of calculus that frames it. What can be calculated and how and when and how not in the changing conditions of the body in love, lust and decay? Is there what Berlinski calls “a fixed something toward which other somethings are tending”?(5) Is it really as simple as the narrator’s binary code conclusion not quite at the end that “Life has only this to offer: itself and death”?(71) I think there is divination happening here. Shells falling, tea leaves scattering in response to a question about limits. Is death a proxy for life, speaking for life, is death all we hear? Is life a proxy for death? What are we not wiling to know?

Our persona, “you,” is a bad patient an impatient queer who despite the dictates of the cancer doctor will not stop smoking and will not keep taking birth control pills. There is a problem in the uterus of the subject, there is also a form of social reproduction that will not persist here. In the prologue the narrator asks you “Is seven such a lucky number?” pointing out that “After seven years you’ve fucked enough women to know better. After seven years, the slant of her eyes tilts your beautiful wavering house, complete with wife and dog, into the chasm behind the curtain.”(10) Right up front this book is rejecting a particular form of belonging prioritizing more drama, more being, more longing.

Our persona, “you,” is a bad patient an impatient queer who despite the dictates of the cancer doctor will not stop smoking and will not keep taking birth control pills. There is a problem in the uterus of the subject, there is also a form of social reproduction that will not persist here. In the prologue the narrator asks you “Is seven such a lucky number?” pointing out that “After seven years you’ve fucked enough women to know better. After seven years, the slant of her eyes tilts your beautiful wavering house, complete with wife and dog, into the chasm behind the curtain.”(10) Right up front this book is rejecting a particular form of belonging prioritizing more drama, more being, more longing.

In the era when a US president speaks about gay rights at the inauguration and when the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force celebrates gay marriage rights passing in several states (with Doyle’s native New York at the forefront), this admission, that the imagined house, the imagined lesbian wife, the imagined validating but still enslaved pet are disappearing is a queer thing. That dream is proxy for what? Legally that dream, the wife, the house, the dog is the dream of even being able to have a proxy because literally marriage rights seem to come down to the ability of one person to legally speak for another, benefit from another’s existence, stand for another in a way the law is bound to respect. What if this book of poems is asking us to give up the idea of legally validated proxy? The character of the poems ungently has sex with a lawyer who thinks sex with a woman will be gentle. Sleeps with her best friend the night before her father’s funeral. Proxy for what? Straps on and thinks about the boyfriend of the girl sitting on her dildo. Proxy for what? Sleeps with their ex-lover’s best friend (who already has a partner) soon before getting back together with the ex-lover. Proxy for what? And it is at this point (proxy meets proxy?) that you fall in love.

The dream that life will be wonderful, that women are gentle, that the friend code is in operation, that we will do whatever it takes to fight cancer, that a lesbian won’t marry or have sex with a man are not dreams that can survive this poetic journey. And should they? Instead the repetition of instances of instead, instead insistent instead offers clarity, identification, but not comfort.

So, if this sounds depressing, it is. But the process of reading the text itself is not without pleasure, just like sex that is illegal, illegible to society and that will probably get you in trouble is not without pleasure at all. These beautiful moments in Doyle’s poetics like “you want to amuse her with your bones,” are so right on about what the body becomes in desire. The landscapes, cabins, mountains and what must be Park Slope, Brooklyn offer opportunities for pleasure in their very descriptions in the poems: “The sun places a little morning in each pale window, sweet water, purple orange nectar.”

You will read this book and you will be astounded at how gorgeous it is to be alive and dying, to be a hot mess falling apart in intimate and public places, to be experiencing a rate of change that changes, a tendency in life towards death which is a limit or not. You will read this book and your organs will react, they will contract and they will open up. And they might help you feel good for a while and they might hurt. And you will know, calculus is happening, calculus is happening, even right now.

0 comments