TFW Interview: Allison Janae Hamilton on "The Black Ain't Project Installation #1: Embodiment"

George Clinton and other funky beats blazed in the background of the chashama gallery in Harlem while the dandy, the boho, the skater, the undefinable moved about engaged in conversations on black romance, red wine, and narrative scenes framed (or not) on white walls. It felt as if I had traveled back to the cool days of black or trekked into a dope afrofuture or happened to be situated in a present where black just is what it is and ain’t what it was all at that same damn time. And it was nothing short of brilliant.

George Clinton and other funky beats blazed in the background of the chashama gallery in Harlem while the dandy, the boho, the skater, the undefinable moved about engaged in conversations on black romance, red wine, and narrative scenes framed (or not) on white walls. It felt as if I had traveled back to the cool days of black or trekked into a dope afrofuture or happened to be situated in a present where black just is what it is and ain’t what it was all at that same damn time. And it was nothing short of brilliant.

Allison Janae Hamilton’s “The Black Ain’t Project Installation #1: Embodiment,” is a timely installation that disrupts the parameters of blackness, gender, sexuality, ability, space and class. What follows are some insights from the brilliant and creative artist regarding the installation.

DM: Your exhibition, “The Black Ain’t Project Installation #1: Embodiment,” is seemingly a response to, a riff off of Marlon Riggs’s documentary, “Black Is, Black Ain’t.” Could you say a bit about the connections and disconnections between your work and Riggs’? And, why the focus on the “ain’t” or the notion of negation?

AH: Yes, the title is definitely a nod to Marlon Riggs, who is one of my all-time favorite filmmakers and writers. The first time I watched Black Is, Black Ain’t, I knew that I wanted to create a project that would also push back against normative understandings of the possibilities of blackness. I focus on the “ain’t” because I’m really interested in talking about all of the things that black people aren’t “supposed” to be and do. I remember when I broke my ankle skateboarding a couple of years ago, a family member said, “Oh Allison, black people don’t skateboard!” and I think hearing that also sparked some inspiration for the project. So now I’m really drawn to the idea of creating art about black skaters and surfers, afro-punk, black burlesque, the black house ball circuit and other queer cultures, and even subjects like trauma, aging, and mental illness that aren’t always put out in the open in our communities. This type of work is the crux of my doctoral research as well.

DM: You note that your focus on the black body in its various forms, especially those subversive forms of embodiment (i.e. scarred, aged, surgically altered, etc.), seeks to “queer traditional tropes of black embodiment.” In what ways is this taken up in your art?

AH: Susan Bordo writes about the body as a battleground, and this is something that’s often in the back of my mind when I write or create art around black embodiment. Dominant cultures have always had the luxury of assigning meanings to the black body in ways that are beneficial to nation-building and other political projects. My interests lie in the responses to these dominant narratives, whether they are self-determinative responses to the dominant narrative (i.e. particular notions of black masculinity enacted by the Black Power and Black Arts Movements) or protective mechanisms that can, at times, disallow a broadened expressive landscape (i.e. respectability politics). I’m finding usefulness in examining the black bodily expressions that are responses to the responses—a collection of queer black aesthetics so to speak. In this sense, I’m not necessarily talking about queer sexuality, but rather the idea of non-normative expressions. Thinking of “queer” in this manner is something that’s been emerging in queer theory discourse in recent years. It can be a slippery slope, but I’m interested in exploring the utility of enacting “queer” in this way. Still working on it!

DM: Your work seems to be a queer and black feminist intervention. Would you agree?

DM: Your work seems to be a queer and black feminist intervention. Would you agree?

AH: I think that’s definitely one way that you could look at it, as the work attempts to complicate normative assumptions of race, gender, and sexuality. However, I consider it to be more of an additional voice in a conversation being sparked by a number of artists, writers, community organizations, and archival projects. I like to think of my work in general and The Black Ain’t Project in particular as a contribution to a really thoughtful dialogue that has been going on for some time, yet manifesting presently in fascinating ways. For example, I’m inspired by brilliant projects relating to black masculinities like Hank Willis Thomas’ Question Bridge and Shantrelle Lewis’ Dandy Lion Project. The Groundfloor Collective is also an amazing group of artists and curators dedicated to exploring a wide range of black expressive perspectives (Lehna Huie, who curated Installation #1 is part of this organization). Additionally, many of the photographs in Black Ain’t’s first installation were taken of members of Bklyn Boihood, an organization doing great work towards promoting positive visibility of masculine of center women and trans men of color. Thematically, I also draw on a long legacy of Afrofuturist texts for inspiration. To call it an intervention might suggest that I’m doing this alone or without literal or artistic conversations with others. I do think, though, that my work offers an important contribution.

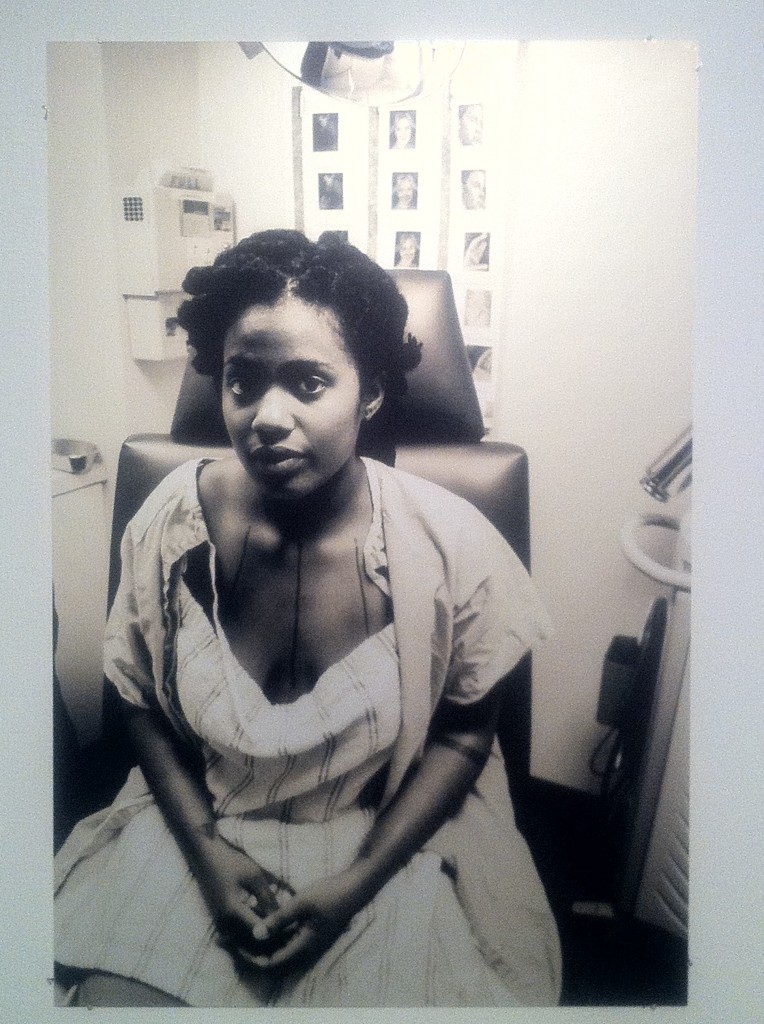

DM: Your piece “The Last Hour or So,” is a haunting visual reminder of the control of women’s (black female subject’s) body. But it is also seems to be a reframe of that control, at least to me. The subject’s body seems to fully inhabit the “space” and is in possession of a certain force of power and agency that causes the eye to see her as subject and not the objectified other

Well, this particular piece is interesting because the idea of a black female subject is a bit complicated here. The photograph you’re referring to is part of a series that follows a friend of mine, Zara, who is going through the process of having top surgery. Zara, who identifies as genderqueer, doesn’t see their body as female, despite the fact that their body may look female to an onlooker or the fact that they are comfortable using both the “she” and “they” pronouns. You bring up an important point, though, about institutional control of bodies, particularly black bodies. I was present with Zara during the long process of finding the right surgeon and navigating the bureaucracy of healthcare and insurance agencies. There were definitely moments of difficulty around that. Because Zara wanted an extreme reduction without having a “male” sculpted chest that is often the norm in FTM top surgeries, it was difficult to find the right team of doctors to understand their needs.

Your idea of the reframe is really captivating. I hadn’t thought of it in that way before, but yes I do think that the actual composition of the photographic scene is an important part of the storytelling process. In “The Last Hour or So” I used a fisheye lens, which definitely created a dramatically highlighted subject. You might say something similar about “…and in between are the doors…” which is very flat and linear. The plastic surgeon’s lines and notes drawn on Zara’s bodies are the main focus along with Zara’s tattoos. They appear flattened out and on the same plane, perhaps a statement on agency making one wonder if the doctor is truly the one doing the marking. But, theoretically, where does agency begin and end? This is always difficult to grapple with, but I definitely think this collection provides a visual platform whereby these types of questions can be thought through.

DM: Your scholarly work is centered on the idea of the “extra-terrestrial.” I love it! Tell us more.

AH: I love Afrofuturism and I’m having a great time exploring the idea of outer space as a metaphor for our lived experiences. The notion of the “extra-terrestrial” tends to pop up in my work in one of two ways. The first is very literal, as I use the term to describe life outside of an appointed homespace. This allows me to think through black diasporan identities and their relationships to imagined homelands. I’m not necessarily talking about Africa here, by the way (a good friend of mine says that Chicago is her motherland!), but a more complex range of homespaces. So, I think it’s an interesting, and perhaps fluid way to examine dispersal, migration, and geography and their impact on our identities and expressions. The other way I’ve been exploring this deals with belonging, culture, aesthetics, and playing with outer space tropes in a way that can account for experiencing and expressing non-normativity. I think of it as the beginning of a framework that I’m continuing to organize around The Black Ain’t Project.

Allison Janae Hamilton is a visual artist from Miami, Florida currently based in New York City. Evoking the aesthetics of Afrofuturism, her artwork attends to the concept of “alien” blackness and pushes the boundaries of black identity through photography, film, painting, costume, and installation. Additionally, she is a doctoral student at New York University, where her dissertation research follows similar themes.

Allison Janae Hamilton is a visual artist from Miami, Florida currently based in New York City. Evoking the aesthetics of Afrofuturism, her artwork attends to the concept of “alien” blackness and pushes the boundaries of black identity through photography, film, painting, costume, and installation. Additionally, she is a doctoral student at New York University, where her dissertation research follows similar themes.

0 comments